The Neustrowski-Watembach Family

Raymond Joseph Watembach is the great-grandson of four of the first Polish settlers in New Zealand. His paternal great-grandparents sailed on the friedeburg in 1872 and his maternal great-grandparents on the fritz reuter in 1876. His grandfather Józef Watemburg was five, the same age as his grandmother Marianna Nejstrowska, when she arrived with her parents and younger brother four years later.

Ray and I met several times before spending a day in his sunny Waitara kitchen in December 2014, delving in and out of books, documents, family trees and photographs, and recorded his memories and his family research.

The walls of Ray’s home heave with books, files, and papers relating to his study of early Polish settlers to New Zealand. He was among the founders of the Polish Genealogical Society of New Zealand in Inglewood in 1992 and remains its president. Ray continues to add to his knowledge of those early Poles and willingly shares that knowledge with anyone wanting to find out more about their families.

Ray’s generosity to scores of amateur genealogists has given him little time to focus on his own family story so it has given me particular pleasure to mould some of his reminiscences into this family story, which follows his father, William.

I thank Ray for his continued guidance, sense of humour, patience and historical explanations that I have used here and in other stories on this page. I wish him all the best.

—Barbara Scrivens

A POLISH WEAVE

by Barbara Scrivens

Irene Mary Fairweather’s ‘sin’ was to marry a Polish man with a German-sounding surname two years before World War 2 erupted.

Despite being born in Waverley on Taranaki’s southern coast, and of Scottish-Irish descent, the local grocery store refused her ‘full service’ during those war years. Even before the war, marrying someone with a German-sounding surname was contentious in English-speaking New Zealand.

Irene was born at the end of World War I and married William Augustine Watemburg in Waitara, on Taranaki’s northern coast, where William lived. Her father, Joseph Henry, had died in 1933 but her mother, Mary, attended the ceremony.

Ray: “The discrimination against my mother was hard on her and there was never enough to eat. Wartime rationing allowed prejudice to be covered up. The English did not discriminate with anything approaching a sensible awareness of ethnicity.

“If we children said we were of Polish extraction, they wouldn’t believe us. They said, ‘You’ve got a German surname, you’re German.’ I only realised years later that during the war Uncle Leo used up his petrol rations for the farm to bring us duck eggs, meat, fish, and sometimes ducks to eat.”

From left, Graham, Ray, and Shirley Watembach, taken about 1946 when Ray was five. His brother, Peter had not yet been born.

One Sunday when Ray was about seven, he discovered what it meant to be Polish in Taranaki.

His widowed paternal grandmother, Marianna, known as Martha Watemburg (née Nejstrowska), moved back to Waitara in 1947 after “keeping herself busy” on her unmarried son Leo’s 75-acre dairy farm on Norfolk Road, Inglewood.

“After Mass these people came up to us, started chatting, and kept lapsing into Polish. We stood outside the church while they talked until midday, my mother getting grumpier and grumpier because there was still the Sunday roast to do.”

Martha’s youngest sister, Apolonia, and husband, Bernard (Ben) Dombrowski, created the excitement. They had recently retired from their farm on Norfolk Road, Inglewood, and moved to Waitara. Contributing to the Polish chatter that morning were Joseph and Agnieszka (née Dodunska) Fabish, who lived next-door to the Waitara church. Agnieszka (Agnes) was Martha’s and Apolonia’s cousin.

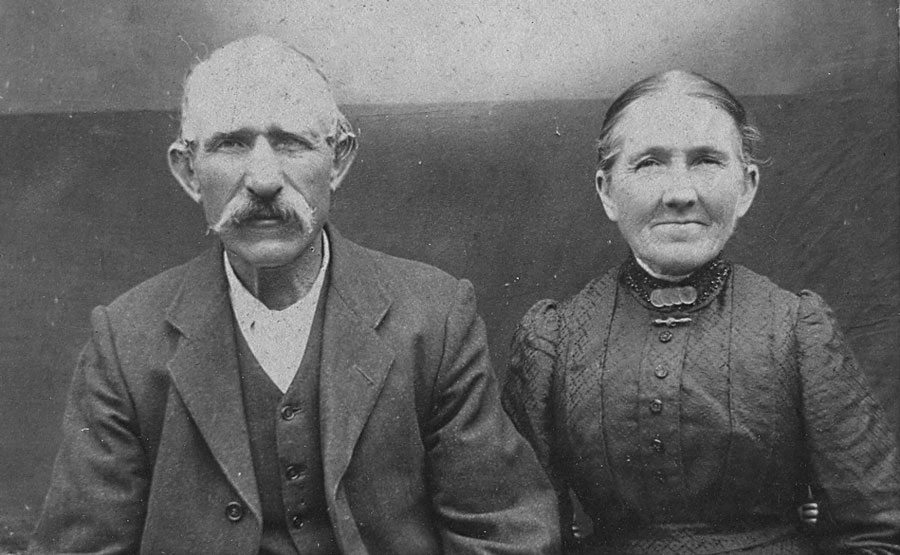

Martha Watemburg's parents, August and Apolonia (née Potroz) Neustrowski.

“Experiencing this older generation of Poles at Mass on Sundays and listening—not understanding—to them talk, talk, talk made me realise I belonged to a wonderful, friendly family.

“When it came to cleaning the church, these Polish ladies would be there with their buckets of boiling water and caustic soda. They would scrub and wash the floor so that the wooden floorboards were clean as a pin and, because the school was next door, my older sister, Shirley, and I would go over and join the old ladies and watch them working—and then we’d get a job.”

Sunday services—with or without a Mass—were integral to most of the Polish settlers’ lives. They had emigrated from Prussian-occupied north-western Poland in the 1870s and 1880s. Their German oppressors forbade them from practising their Catholic faith in their own tongue. Seventy years later Ray saw how the settlers’ children remained spiritually grateful for their parents’ courage in leaving their homeland.

Martha as a young mother with her mother-in-law, Katarzyna (Catherine) Watemburg, and from left, Albert, Beatrice at the back, and Vera.

“Anything they could do to improve themselves was a gift from God and they were thankful for their new lives. In those early years the so-called road was a sea of mud and stumps—a track cut through bush. Even bullock drays got stuck in the mud, but the early settlers and surveyors all used that track, and the Poles would trudge for miles to Sunday Mass.

“Grandmother Neustrowska’s family walked from York Road in Midhirst to the church in Inglewood. That’s more than ten miles, fasting, no bridges. They had to wade or rock-hop through seven streams. They carried the babies. They always had some family, or a friend at Mass, who they would visit and share lunch with. On Sundays when there was no priest, they would gather at a house, read the lesson for the day, and sing the service. Cardinal X Dalbor organised it so the New Zealand Poles had the correct tracts, the Słowo Boże [word of God]—and the Poles were great for singing.”

Two of Martha’s brothers, Paul, born in 1880, and Joseph, born in 1882, fought in France during WWI with the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces’ 13th reinforcements. Their war records show that both were wounded in action in September 1916, and Joseph again in July 1917.

Before they enlisted in 1916, they had been employed as bushmen by a J Kennedy in Karioi, on the Waikato west coast. Their younger brother, Isidore (Sid), born in 1888, had worked with them, but seemed to have had an accident that brought him back to Waitara, where his parents then lived, and where he was employed by the Waitara Freezing Works. In 1916, the NZEF declared Sid unfit to serve.

In its “Attestation for General Service” of Ben Neustrowski in 1917, the NZEF noted that he was farming a block of land in Whangamomona, was single, and self-employed. Unlike his older brothers Paul and Joe, Ben’s military papers seemed to hone in on his “Alien parentage.”

On his farm in Aotuhia, south of Wangamomona and adjacent to the Whanganui National Park, Ben built a house identical to that of his parents’ in York Road. Because of that, it is not clear whether the photograph below was taken at Ben’s house in Aotuhia, or his parents’ below Mount Taranaki in York Road. The absence of August and Apolonia Neustrowski suggests that Ben’s siblings may have made the trip specially to visit him.

On the veranda from left are Paul and Joe Neustrowski, and Ben Neustrowski to the right. Agnes, then married to Herman Schultz, is seated and with her children, Joe, Margaret, and Helen. Apolonia junior (Polly) is standing on the far right. Standing in front of the veranda on the far left is August Volzke junior, a fellow bushman and family friend, the son of August and Emilie Marie Volzke. (More on the Volzke family later.)

Ray: “The war clothes were good quality, hard wearing. Uncle Ben would not have thrown them out.”

“At the left-rear of the house, there would have been a Polish food cellar for storing things like root vegetables. Aotuhia was awful, hill country, much worse than in Stratford. They did a lot of burning, but not all the trees fell, as you can see from the stumps. They were also plagued with wild pigs—so much so that the county paid a shilling a snout.”

_______________

“We enjoyed our relations, more so as my mother played the piano and my father played the accordion. When rationing ended—about 1950—we were able to go to Uncle Leo’s farm on Norfolk Road. Dad took a bag with him and the first time we stayed overnight, we wondered what was in it—until the evening when he pulled out his button accordion. Leo, Dad’s brother, had his accordion, the mat was rolled up in the front room, the furniture pushed into the bedrooms, the neighbours came over, and everybody would have a dance with Dad and Uncle Leo playing.

“It was a real bonus when our uncle Albert Watembach came up from his gold mining in the South Island, as he played the piano accordion. Dad and Leo mostly played button accordions, but Albert also played a violin and Jew’s harp. Leo sometimes played a zither and a Jew’s harp. There was another Watembach brother, Alf—Frank was his proper name—and when he turned up, which was quite rare, he played banjo as well as button accordion. So there was always music and good times with family and neighbours. It wasn’t that we were wealthy. We were wealthy with music and friendly people on the Polish side of the family.”

Photographed at Leo's Norfolk Road farm around 1940:

Ray’s grandmother Martha is on the far left. Next to her is Ivan Antunovic, who Ray's aunt Beatrice married in 1919, and Leo

is next to him. Behind Leo is a friend, Bill Skurr, and next to him is Ray’s father, William. Beatrice is on the extreme

right. In front are Max and Leona Antunovic and Ray’s mother, Irene, is looking down at his sister Shirley.

Ray remembers one of Leo’s neighbours, the Wisniewski family, with “10 or 12” children living on the corner of Norfolk Road. Albert Watemburg lost his farm on the other side of Leo during the 1930s’ Great Depression. Before he turned to gold mining, Albert leased Maori land in Kawhia, about 250 kilometres up the coast.

“Being close to the harbour you got a free feed out of the water.”

Apolonia and Ben Dombrowski farmed close to other Poles on Norfolk Road, opposite Graham Hastie, who had a Polish mother (Agnes Duschenski). Another Duschenski farmed closer to the mountain and the non-Polish Smith neighbours often joined the Polish social gatherings. Leo taught Ray Smith junior to play the accordion.

The Dombrowski contingent at the 1907 wedding of Ben Dombrowski to Apolonia (Polly)

Neustrowski junior on either side of the matriarch of the Dombrowski family, Justina née Stachurska:

From left: Frank Dombrowski; the groom, Ben; the bride, Apolonia; probably 17-year-old Albert Dombrowski; Rose née Dombrowska

Eagar at the back with her hand on her daughter Lily’s shoulder; mother of the groom Justina Dombrowska; Ada Gilbert in front

of an unnamed woman and next to her mother, Martha née Dombrowska Gilbert; Barbara née Potroz Dombrowski and her husband,

Joseph Dombrowski.

“Things were not easy in those days so nobody came visiting empty handed. I remember my Aunt Vera going from Leo’s place to one of the Duszenski farms one evening for a card game. She took freshly made scones with home-made butter and whipped cream on top of blackberry jam, a roast duck she stuffed with apricots, raisins and sultanas, and of course the men always had some beer or blackberry wine to drink—but we children were not allowed to even sip.”

This slice of Polish culture in predominantly English-speaking colonial New Zealand was a direct result of the new colony’s need in the 1870s for immigrants to help build its infrastructure. British settlers from 1840 soon occupied the optimal and flattest lands in Canterbury, Taranaki, the Wairarapa, and Hawke’s Bay—but building roads, railways and bridges proved more problematic in the rest of a country dominated by steep hills and fast-flowing rivers. The explicit intertwined name—the Immigration and Public Works Act of 1870—reveals how much New Zealand depended on immigrant labour.

_______________

Martha Watemburg was a natural matriarch. Born in Gręblin, near Peplin, she turned five two days before the fritz reuter docked in Wellington harbour. With her, her parents, and younger brother, Johan (later known as John), were more than 250 other Poles from the same Kaszubian and Kociewiean regions of Prussian-occupied Poland. Her baby brother, August, had died of heat exhaustion on the three-month journey from Hamburg.

The Poles who settled in New Zealand may have gained their freedom, land, and a future for their children, but they lost their language.

By the time Martha was born, the germanisation of the Poles in north-western Poland was well under way. After the first Prussian partitioning in 1772, the new rulers started re-naming geographical features and towns, and from about 1848 were germanising Polish names in official documents. By 1870 the Prussians had banned Polish schools and had created a law prohibiting possession of any Polish reading material. Bismarck’s secret police increasingly harassed Catholic Poles as they looked for people breaking those new laws.

Many Polish parents retaliated by refusing to send their children to German schools. When they arrived in New Zealand, few of the adult Poles were literate and years later still signed official documents with a cross.

The Poles who settled in New Zealand may have gained their freedom, land, and a future for their children, but they lost their language. August and Apolonia allocated two rooms in their house as a school for local children, including their own, but future generations were destined to become English-speaking Poles. August and Apolonia may not have been able to read and write, but they made sure their children did.

In the 1870s, the Polish settlers in New Zealand could not understand the language spoken by immigration officials. About 50 fritz reuter Poles accepted transfer onto the ss taupo and continued their journey up the coast to New Plymouth. The first Polish immigrants to settle in Taranaki came ashore in whaleboats at the Puke Ariki landing, now the site of New Plymouth’s museum-library of the same name.

The immigrants walked up Brougham Street to Marsland Hill and the former British military barracks. The buildings—empty of troops after the 1860s Taranaki Wars—became an immigration hostel providing free rations until people found work. August Neustrowski took a job in Bell Block, north of New Plymouth, clearing scrubland for an English farmer.

“Things were so unsettled in those days. Some of the land had been Maori farms that reverted to scrub during the wars. Some English people moved out of the area entirely. Some went to Nelson, and some returned to England. The buying and selling of land was destabilised by the unlawful actions of some settlers and government officials.”

Agnes, the first of six New Zealand-born Neustrowski children, arrived on 14 April 1877 at their new home in the Hua village. Although a Hua Street remains, the village has been absorbed by Bell Block. The official birth record incorrectly spells Agnes’s surname “Neustrowsky.”

Once they had a bit of money they bought pork and started making Polish sausage, curing hams, bacon, or even fish, by hanging it all in the chimney.

“They moved to Inglewood when great-grandfather started working on the railway line. The first line went from New Plymouth to Waitara. A new line went inland to Lepperton junction, through Inglewood, then on to Hawera, and eventually to Whanganui. Some of the Polish men worked on the railway line, sometimes with food and accommodation supplied.

“My great-grandparents found a little one-roomed cottage in Inglewood. My grandmother described it as ‘one room, with a lean-to at the back for washing and drying clothes.’ The room had a dirt floor and they made dried fern mattresses. The parents slept on the floor and the children in the rafters. The fireplace was about two metres wide and about a metre deep. It didn’t have a brick chimney, so they lined it with corrugated iron supported by green timber. Once they had a bit of money, they bought pork and started making Polish sausage, curing hams, bacon, or even fish, by hanging it all in the chimney.

“It was a huge event when the French Marist priests started visiting. There was no presbytery and when the priest visited the Poles in Inglewood, he stayed with the Neustrowski family. All the Poles gathered in this one room for the service, so there must have been quite an overflow. My grandmother told me the children would all be up in the rafters and looked down on the parents while the priest talked.

“On weekdays, great-grandfather worked on the roads for the government and contracting, felling trees. He was known to be scrupulously honest. I found out that he later organised other Polish men to help him chop down 680 acres of standing bush at Ngaere, south of Stratford, for an English gentleman who refused to pay the correct amount. He thought the dumb ‘German’ wouldn’t know the difference between 600 acres and 680 acres, so great-grandfather August took him to court. The Englishman ended up settling.”

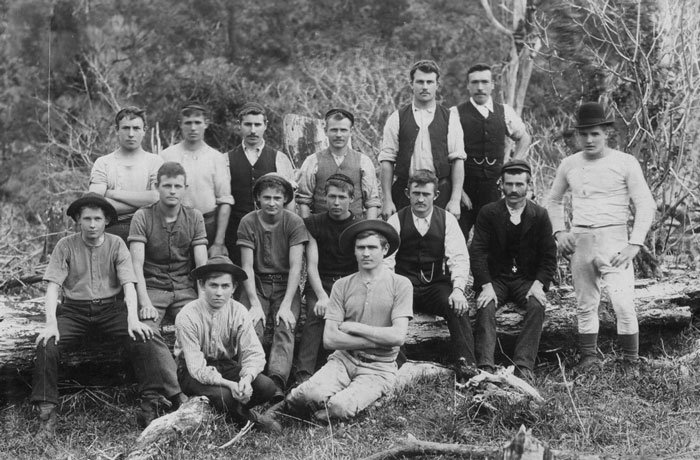

August Neustrowski’s was among several Polish bush-clearing groups in Taranaki in the 1870s. During the working week, they lived in tents such as these.

A close-up of the same group. Ray has been able to identify Vincent Meller,1 with the watch chains in the back row, and his uncle John (Johan) Neustrowski, also with watch chains and sitting on the log third from the right.

Another of the bush-felling groups that Vincent Meller worked with. This time he is second from left. If you can identify any of the other people in these three photographs, please let us know.

One group of bush-fellers made page two of the taranaki herald on 8 March 1887:

A party of contractors working on the Egmont Road have suffered a considerable amount of damage at the hands of some people who had passed by. The contractors, who are Polish settlers living several miles away, left for their homes on the Saturday afternoon, and on the following Monday found that somebody had slept in their tents on Saturday night, and had made free with the provisions. The hospitable Poles have no objection to their chattels being made use of in this way, but were much annoyed to find that the unbidden guests had destroyed what food they could not eat, and had torn up several books and scattered the leaves for miles along the road.2

From 1880, Poles started building on their own land. They bought—by auction—drawn lots on the Mount Taranaki (then Mount Egmont) side of Mountain Road (SH3). The English settlers had already taken up the cleared land on the other side of the road, confiscated from the local Māori by the New Zealand government after the Taranaki Wars. The English called the area between the road and the mountain “the German settlement,” a term that riled the Poles. In Inglewood the locals renamed James Street “German Street,” again not accepting the ethnicity of the Polish families living there. It later reverted to James Street.

“It was four lines on a map, solid bush, full of vines, water, swamps, and no road to it.”

“When land became available to the new settlers, great-grandfather August Neustrowski bought a farm. It was four lines on a map, solid bush, full of vines, water, swamps, and no road to it.”

August’s name appears in the October 1882 return of the freeholders of new zealand, compiled by the government’s property tax department.3 The roll states that he was a labourer, lived in Midhirst and owned 85 acres in Taranaki, valued at £131. The same return shows two of his brothers-in-law, Anton and Thomas Potroz, each a “labourer of Midhirst,” owning 41 acres valued at £81. The property tax commissioner, in his introduction to the roll, noted that on that date there were about 143,000 non-Māori men and 71,240 landowners in New Zealand.

“Individual property owners were the only ones allowed to vote at that time. This excluded most Māori. The Poles put deposits on the land, but they had no capital income, which is why they started contracting.”

The men in August’s group all needed to save as well as earn enough for day-to-day expenses for themselves and their families before they could start spending time clearing the properties they bought on or near York and Rutland Roads north of Midhirst, and Climie Road south of Stratford.

“The Polish side close to the mountain was rougher and colder than the other side. It was mostly solid bush but there were some open spaces around the Norfolk Road [Midhirst] because during the Taranaki Wars the Māori made refuge clearings to grow food away from the battle zones.”

_______________

Joseph Watemburg on the Avon river in Christchurch. Like other Marshland market gardeners, he took on out-of-season jobs. Scything waterweeds on the river’s edges provided him with another source of income and helped clear the river for the already popular punting pastime enjoyed by the city’s more affluent inhabitants.

Martha née Neustrowski’s husband, Joseph Watemburg, was born as Józef Watembach in Rytel, near Chojnice in the same Kaszubian area as his wife, but on the western side of the Tuchola forest. He sailed on the friedeburg from Hamburg to Lyttleton in 1872 with his parents, Wojciech and Katarzyna, younger sister Marianna, brother Franciszek, and about 90 other Kaszubian Poles. His parents’ names are spelt Albrecht and Catharina on the ship’s manifest. Marianna became Mary, and Franciszek became Frank.

The friedeburg arrived in Canterbury at a time when labourers and domestic staff were in high demand. First, Albert and other Poles worked on the Banks Peninsula, stumping, and collecting grass seed. They then took up the offer of land leases in Marshland, a swampy area north of the main Christchurch settlement. A few years later, they were financially able to buy the land they had improved through drainage and removal of drowned trees—at considerably higher prices. (See marshland: the place where flax grows profusely.)

The Poles established market gardens in Marshland that supplied much of early Christchurch’s vegetable needs, and specialised in onions.

By his late twenties Joseph had carved a comfortable livelihood for himself growing and selling his produce. Missing was a wife. The dearth of suitable women in Marshland led him to the largest Polish community in New Zealand at the time—800 kilometres away in Inglewood, Taranaki.

Alan Mulgan described the route in his book from track to highway.4 In 1908 Christchurch was a 12-hour sea journey from Wellington, “the sea portion of the broken journey… apt to be highly uncomfortable.” Joseph did the trip in 1896 or 1897 and once in Wellington, he still had to get to Taranaki.

… for Joseph Watemburg—oldest son—meeting and marrying Marianna Neustrowska was worth the time and effort.

Until a “steamer express” service was established several years after Joseph went looking for a bride, travelling was “fairly arduous, and comparatively few New Zealanders went far unless they had to.”5 By whichever means and however long it took him, for Joseph Watemburg—oldest son—meeting and marrying Marianna Neustrowska was worth the time and effort. After his success, several other marriageable Polish Marshland men followed his example.

“In northern Poland it was customary to marry by arrangement, not for love but to improve your social status. I think grandfather must have had the mindset that it was time he got married, and to someone with a similar background.”

Official marriage records show “Martha Newstrowski” married “Joseph James Watemburg” in 1897.

The misspelling of Polish names continued after death. Marianna Watembach’s Polish name is impossible to find in Waitara cemetery where she is buried. Her headstone says “Martha Watemburg” and her husband’s “Joseph Watemburg.” Her married surname seems to have fewer variations than her maiden name. During my research for this story I did not find one correct feminine version of Marianna’s maiden name, Nejstrowska.

The fritz reuter passenger manifest, transcribed in Hamburg, spelt it Nietswowsky. Variations include Newstrowski, Neustnowski, Neustrewski, Neustroski, Neutroski, and Nesterowski. In New Zealand, the family accepted the modification Neustrowski, and later generations, Neustroski.

Joseph and Martha Watemburg’s house on Marshland Road, circa 1905. Judging from the similar clothing worn by Katarzyna Watemburg, Martha and the Watemburg children on the veranda (from left: Beatrice, Vera and Albert), this photograph was taken the same day as the earlier close-up. The flowering onions in the foreground carry the seeds for the next season’s harvest.

“My cousin Kate Bisman [another of Albert and Katarzyna’s great-grandchildren] took me past the house in the 1970s. Albert had it built and sold it to Joseph and Martha and their growing family.”

The house is completely different from the “little better than a hovel” in Rhodes Swamp, where Albert and Katarzyna first lived with their children in 1883. The “hovel”description came from Albert’s lawyer, whom Albert had employed to challenge a claim against him from a surgeon, Dr Russell. The surgeon had removed an 89lb abdominal tumour from Katarzyna, “no alcohol at all being given her.” The case was so unusual that the surgeon offered to waive payment for the procedure. Then, Albert could not afford to pay the ancillary costs, and took out an advertisement pleading with the community to help his wife. The judge noted Katarzyna’s meticulous account book showing their repayments to Dr Russell—including “two loads of carrots”—and dismissed the surgeon’s claim. (For the full story, see mary le lavaseur: marshland’s first wedding.)

_______________

Ray discovered his aunt Agnes (Martha’s younger sister) on the St Joseph’s School roll in Papanui, Marshland’s neighbouring suburb. Because Martha was known to get homesick, this made him wonder whether she was at first lonely in Marshlands and whether Agnes had been sent to Marshland by their parents in Taranaki to comfort her sister, or to help with the first pregnancies and babies.

“Grandmother told me she was sent out to service at 11 and became so homesick that she could not stay in one place for longer than six months.”

Martha told Ray that she worked for a family of bakers in New Plymouth and as a maid for mountaineer Arthur Ambury, who died on (then) Mount Egmont in 1918 while trying to rescue another man.

“She was taught to read and write in English, and Catechism, by the Opunake Harbour Board engineer’s Irish wife. Grandmother was their maid, and did chores like feeding the chooks and cleaning the silver and pots and kettles. Her knowledge of the English language was adequate but limited, because she had little access to schooling, but she always read the daily papers and magazines.”

“… in Poland the Germans would only allow them to eat the meat of whatever died in the fields, or suspiciously.”

For many Polish settler children, the needs of the family and their farm took precedence over schooling. Martha’s going into service would have meant one fewer mouth to feed for August and Apolonia Neustrowski, and an extra income.

When Martha arrived in Marshland as a new bride, Joseph had already completed the initial draining and clearing of his property. The resulting soil was ideal for crops such as onions, carrots, and the garlic essential in Polish cooking.

“In Poland, they needed the garlic to kill off harmful bacteria before they smoked their meat. The first comment that great-grandfather [August Neustrowski] apparently made about eating meat in New Zealand was how wonderful it tasted fresh. In Poland, the Germans would only allow them to eat the meat of whatever died in the fields, or suspiciously. There was no fresh meat for Poles.”

At least four Watemburg children attended Christchurch’s Yaldhurst School at the same time.

In this 1913 school photograph, Albert is in the back row, third from right. Leo is in the row below, also third from right. Vera is standing in front of the teacher in the third row and William sits on the right in the front. Beatrice had by then moved to the Catholic college in Barbadoes Street. Missing from the photograph is Alfred, who enrolled in 1914.

the press newspaper in Christchurch described Joseph in 1915 as “a farmer, who lived at Yaldhurst Road.”6 Beatrice and Vera joined Yaldhurst School in late 1910, which suggested that was when the family moved from their Marshlands farm.

_______________

This circa 1916 Neustrowski family photograph was taken as a memento after Paul and

Joseph (Joe) joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

Seated from left is Martha, Isadore (Sid), Apolonia senior, August, Apolonia junior (Polly), and Agnes. Standing from left is

Ben, Joe, Paul and John.

Paul’s and Joe’s military records have helped put a probable date on the photograph above, because both enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in 1916. Both men, unmarried, put their father as next-of-kin. August and Apolonia had by then retired to Waitara. Their eldest son, John, had taken over the their York Road farm, and was running a herd of about 50 cows.

The irony would not have been lost on August that the same government that took away his sons to fight on the Allied side, proclaimed him and his wife “enemy aliens.” After living in New Zealand for 40 years, and despite August’s being naturalised as a British subject 30 years earlier, both appeared on Waitara’s Enemy Alien register. They were then both aged 67, and gave Poland as their country of birth. According to the New Zealand government’s WWI laws and regulations, enemy aliens had to register at their nearest police station, were not allowed to travel more than 20 miles from home without informing the police, and were not allowed to vote in elections.

Despite arriving in New Zealand aged two, John Neustrowski received the same enemy alien treatment in Stratford.

John Newstrowski, aged 27, married Rosalie Miller, aged 18, in 1901. (These are the BDM spellings on their marriage record. Rosalie was Rosalia Meller, the daughter of Jacob and Rosalia née Gajkowska Meller, who arrived aboard the fritz reuter in 1876.) In 1916, John and Rosalia Neustrowski had eight living children. (Their fourth, Mary Agnes, had died aged three months.) John’s brother Ben was by then farming in Aotuhia, and Sid was working at the Waitara Freezing Works. His sister Agnes had married Herman Schultz, and Apolonia had married Ben Dombrowski.

Although Martha visited her family regularly before 1915, by 1916 she was also living in Waitara. Joseph Watembach had died suddenly, and she had returned permanently to Taranaki with her four young sons.

Rosalia Neustrowski died aged 38 of a cerebral embolism after giving birth for the thirteenth time in March 1922. The baby did not survive, and was not named. It is not clear how many of the surviving children were still living at the farm at the time. According to Rosalia's death certificate, their ages ranged from one year to 19. Their eldest daughter, Kathleen Polly, had married August Dodunski in 1920, and their eldest son, John Francis, was by then 18.

John’s parents, August and Apolonia, returned to the farm from Waitara in 1926 when John’s cows died after developing milk fever. According to family story, John and the children still living with him moved into accommodation next door, on the farm of Apolonia’s brother Anton Potroz, while August and Apolonia tried to again build up their farm.

August Neustrowski died in Febeuary 1927, and Apolonia senior just six months later. They are both buried at Midhirst Old cemetery.

The siblings got together for another family photograph at the Dombrowski’s 50th wedding

anniversary celebrations in 1957.

Sitting from left is Agnes Schultz, Martha Watemburg and John (Jack) Neustrowski. Standing immediately behind them is Polly

Dombrowski and Ben Neustrowski. In the background looking at the camera is Joe Schultz, Agnes and Herman Shultz’s only son, a

neighbour of Polly and Ben Dombrowski.

_______________

Christchurch’s tram horses munched through their fair share of Joseph’s carrot crop. Their stables at the Riccarton Racecourse on Yaldhurst Road would have made them among the more convenient of Joseph’s regular customers. Did Joseph have a contented swing in his step as he made a delivery to the stables late on Saturday 13 March 1915? Or was he feeling the pressure of providing for his family? All we know is that as he approached the rececourse stables, he had a heart attack and died immediately. He was 47.

the press said Joseph was last seen alive at 6.30pm that Saturday, and that his body was found on the racecourse at 2.30pm on Sunday, the official date of his death. All 11 New Zealand newspapers running the story said, incorrectly, that he was 53.

The new widow should have had the support of Joseph’s mother, known as a “kindly woman always walking around Christchurch with bags of fruit and vegetables for people who did not have enough.” But for Katarzyna, widowed in 1908, her eldest son’s sudden death became more than she could bear. At Joseph’s funeral she threw herself on his lowered coffin and died 12 days after, aged 72.

Joseph does share a grave in the Linwood cemetery in Christchurch—with Olive, his and Martha’s daughter, born between William and Leo, and who died in 1908 aged eight months.7

The 2011 earthquakes toppled the Watemburg headstones in the Linwood cemetery but did not destroy them completely. Joseph and Olive Watemburg’s shared headstone is cracked and on the ground but a good portion of the lettering is still clinging on.

Katarzyna Watembach lies with her husband, Albert, in the Linwood cemetery. Like many of the old headstones, the lead lettering has become detached as the stone has weathered but her anglicised name is still intact.

Although there was support from other Polish families in Marshland, Martha knew she would not be able to carry on her husband’s market gardening. An exodus of Watemburg children from regular schooling during 1915 reflects the crevasse their father’s death created.

Beatrice, the eldest, was then 16 and Alfred, the youngest, was six. School records show that second-born Vera left Yaldhurst on 18 June 1915 to go into “domestic service.” Beatrice had already done the same. The older girls suddenly needed to earn to help support the family.

Albert Watemburg, aged 13, could be trusted to travel the 15 kilometres from Marshland to Yaldhurst, where he finished off his final school term in November 1915, but his younger brothers transferred to Marshlands School on 22 September, confirming Ray’s belief that Martha organised the family in conjunction with school terms.

“The war disrupted legal practices and, with men away, slowed property sales. Shipping services, while regular, were weeks apart, so grandmother would have waited a good while between selling the property and receiving the money.”

Martha eventually moved in with her cousin, Martha Szymanska (née Dodunska) and her husband, Albert, in Marshland. This explains the younger boys’ move to Marshlands School and Albert named as their guardian on their school admittance forms.

Ray remembers stories of how his Aunt Vera created excitement in the family when she worked as a telephone-exchange operator at Wigram Air Force base. Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith, after making the first trans-Tasman flight from Sydney to Christchurch in September 1928, took her up in his aeroplane.

When he died, Joseph Watemburg had two surviving brothers, Frank (Franciszek) and John, both childless, and two married sisters, Mary le Vavaseur (Marianna) and Annie (Anna) Kavanagh, in Christchurch.

This studio photograph of Mary Watemburg le Vavaseur with son, John Joseph, and daughter, Kathleen May, was taken around 1906 in Christchurch.

Annie Watemburg Kavanagh with her husband Jack (John) and children, Margaret Catherine and John junior. The young man about to leave with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force is Ivan Antunovic, a friend of the family, who married Annie’s niece Beatrice Watemburg in 1919. (Ivan and Beatrice appear in the 1940 family photograph earlier in this story.)

_______________

Martha left her daughters Beatrice and Vera in Christchurch knowing they had family support through the Watemburg aunts and uncles, and Szymanski cousins in Marshland. She gathered up her sons, then aged between six and 13 years, and moved back to Taranaki and her Neustrowski roots.

She bought a house in Waitara near her parents and maternal aunt and uncle, Josefina and Anton Potroz, who had all retired and lived next door to one another in Waitara’s Queen Street. Anton, Josefina, and 18-month-old Jacob had sailed with the Neustrowski family on the fritz reuter in 1876. In 1916, Martha’s sister Agnes lived in Kawhia but the rest of her siblings were still in the Taranaki area.

Martha knew how to start again. She had seen her parents and other Polish families carve farms from the apparently impenetrable sub-tropical Taranaki rain forest. Perhaps she felt her brothers had the ability to guide her four fatherless sons? By then both Ben and Joe Neustrowski had reputations as competitive axemen.

_______________

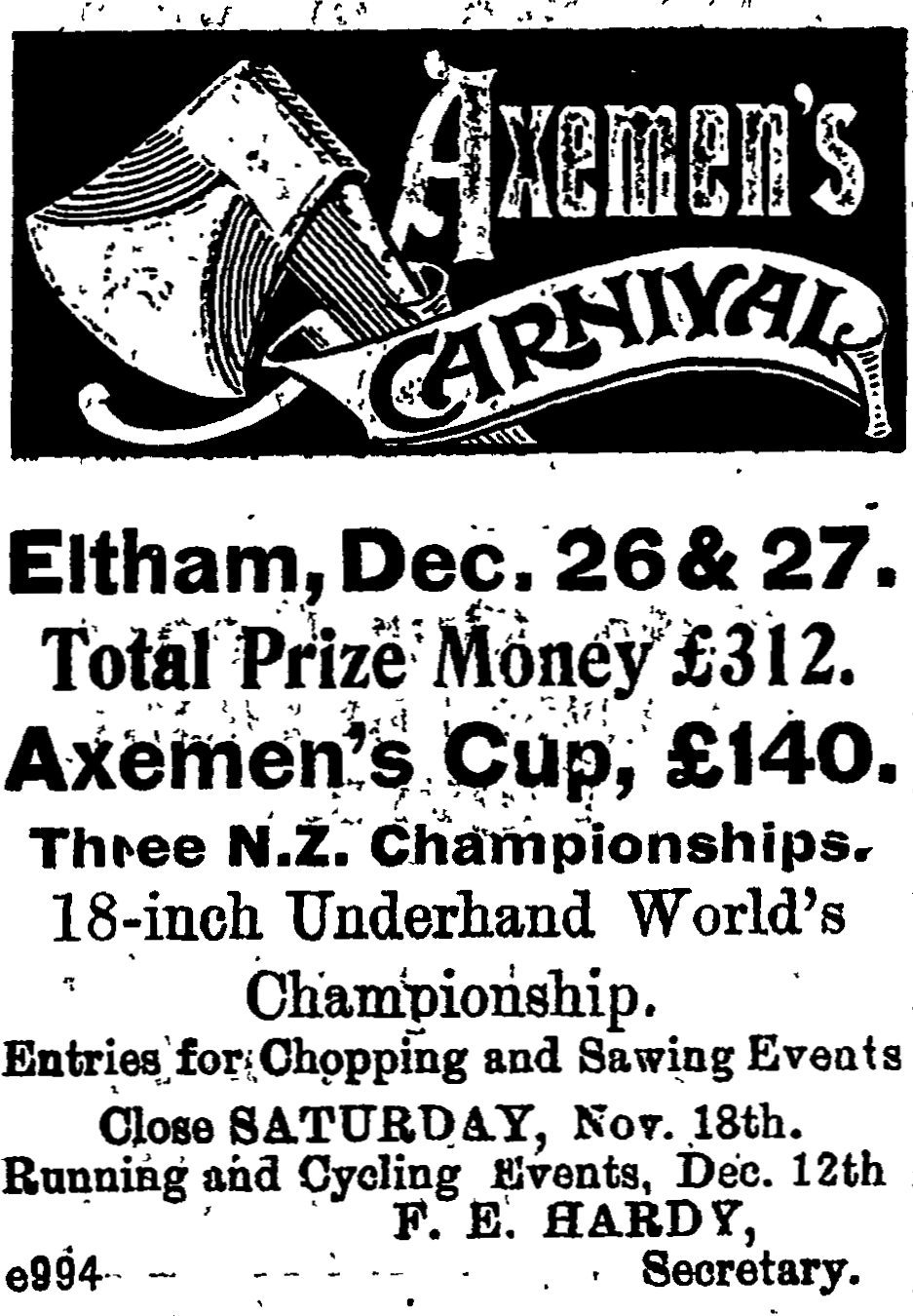

Nearby Eltham’s “Axemen’s Carnival” was in its fifth year in 1905. An advertisement in the taranaki herald on 16 November, offered three New Zealand championships and attractive prize money.

Compared with jumping, driving and guessing competitions (first prize a sewing machine), offered at the Egmont Agricultural and Pastoral Association’s show in November 1905, the Axemen’s Carnival will have whetted another kind of appetite.8

Ben Neustrowski, after winning the most prominent of the three New Zealand championships offered by the Axemen’s Carnival in 1905, the “18-inch Underhand World’s Championship.”

Joe Neustrowski entered the 24-inch championship, and lost… until a Polish neighbour, August Voltzke (Wolski, Volsky, Voltske) had the photograph below developed. (August and Maria Voltzke and their infant daughter Augusta had been fellow passengers with the Neustrowskis on the fritz reuter.)

August Voltzke’s photograph showed the final stages of the 1905 Axemen’s 24-inch championship and proved Joe Neustrowski had finished before the ‘winner.’

“He set up the camera so that he would have a panoramic view of his neighbours taking part. There was great-uncle’s block on the ground and the Englishman who was declared the winner was still chopping. Voltzke went to the judges with his incriminating evidence. Joe apparently said, ‘What am I going to do with a silver trophy standing on my shelf when I’m out chopping trees most of the day? I’ll take the money,’ the equivalent of about seven weeks’ wages. So he took the purse and the Englishman had the honours.”

Joe and Ben continued competing, but Joe had to stop after a shoulder injury he acquired during combat in WWI.

_______________

Martha bought a two-roomed house near the beach and ford that used to cross the Waitara river. The core of the building was a former butcher shop that used to supply meat for the British military during the Taranaki Wars.

“They slaughtered stolen Māori cattle to feed their troops in what became her living room. Mr Kibby, who owned the furniture shop, wanted to build a house on the section so he put the [butcher’s] room on rollers and moved it next door. Somebody added another room on the end, a veranda along the front and a stained-glass front door. Some years later my father and his brothers built two large bedrooms on the front and a short passage.”

Once her sons left home Martha rented the house, below, and moved to Leo’s farm.

Ray remembers stories of his father’s first job, at the Waitara Freezing Works.

“The whistle would blow for the men to go to work. They sent a runner to get my father, my uncle Alf, and some other small boys who then had the job of pushing carts of frozen sheep and lamb carcasses—wrapped in stockingnet—onto the wharf. A man would unload them onto the lighter, the boys would push them back up to the freezer door and this would go on until the refrigerated boat was loaded. They used to get a tiny amount of money, and I don’t know whether they got any free or cheap meat, but the boy who used to round up Dad and the other lads told me in his old age that Dad was one of those he came to get. I don’t think too much schooling was done.”

Her own lack of schooling may have been a sore point for Ray’s grandmother. Ray was about 10 years old when he asked her to teach him some Polish.

“She snapped back at me and said that I should ask my dad. It turned out that when she tried to teach the boys after their father died, they misbehaved and wouldn’t learn.”

Perhaps Martha and other immigrant Poles should have made more of an effort to preserve their mother tongue. Perhaps teaching her children the nuances of the Polish language after her husband died was an avenue—or an argument—for which she did not have the energy at that low point in her life. Despite that, and her lack of formal education, Martha instilled a strong sense of Polishness to her children and grandchildren.

William, born in 1906, was caught growing up and needing to earn a living in the period of economic uncertainty in New Zealand after World War I, exacerbated by the mass unemployment following the New York stock exchange crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.

“One of the things about the Depression was that it broke up families and sent people looking to make a living wherever they could. When Albert couldn’t make enough of an income in Kawhia he went gold mining down the West Coast of the South Island, inland from Greymouth at a place called Kaimata, near Lake Brunner. Dad and Ben Dombrowski’s son, Laurie (Laurence), were looking for jobs and agreed to meet Albert in Collingwood in Golden Bay so they went gold mining there.

“When there wasn’t enough gold in the Collingwood area, they moved down the West Coast and stayed there until about 1936 when Dad and Laurie came back to Taranaki. They were both working at the Patea Freezing Works when Dad met my mother and got engaged. Laurie was married by then and came up to Waitara too. He married Helen Margery Reeves, and she was known as Aunty Marg to us. They bought a house on the corner of Mouatt and Richmond Streets, had 12 children and they all became a part of our lives. [Laurie’s father is listed as “Combrowski” and Laurie (Laurence Bernard) as “Dombroski” in marriage records.]

“Grandmother leased a bit of extra land so she could keep a cow and a pig. She made her own butter. I don’t know whether she made cheese but always she made Polish yoghurt. I remember it sitting on her bench in the sun or in the warmth when I was a boy, and she would simply have it covered and ate her yoghurt every day.

“She had a very intense spiritual life in her old age. She would walk the mile or so to the old church in town for Mass every morning and on her way back buy a loaf of bread if she needed one. At her gate she had an old flax kete [a Maori woven basket] and she’d pick that up and walk to the beach, or the bay as she called it, and pick up fine sticks of driftwood that had washed down with the floods so she could light her fire without having to chop kindling.”

Martha Watemburg died at 91, a feisty Pole to the end.

Ray has fond memories of her. He could not influence the erroneous spellings of his family names, but he has made sure his reverted to the original Watembach.

“It was the least I could do.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated January 2023

UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE WATEMBACH COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Ray found that in early Polish Catholic church records, this family’s name appears as “Meller.” A later marriage record has the germanised spelling Müller. The family, from Kokoschken (now Kokoszkowy) arrived in New Zealand on the fritz reuter.

- 2 - Taranaki Herald, 8 March 1887, RESIDENT MAGISTRATE'S COURT, through the Alexander

Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand:

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/8833298. - 3 - A copy of this return is available on CD from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists:

https://www.genealogy.org.nz. - 4 - Mulgan, Alan, From Track to Highway, A Short History of New Zealand, Witcombe & Tombs Ltd, Wellington 1944, page 94.

- 5 - Ibid.

- 6 - The Press, issue 15227, 15 March 1915, page 8, CASUALTIES, FARMER’S SUDDEN DEATH, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 7 - These deaths confirmed through the New Zealand department of Internal Affairs website:

http://www.dia.govt.nz/Births-deaths-and-marriages. - 8 - Taranaki Herald, 16 November 1905, page 7 Advertisements Column 3,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH19051116.2.74.3