The Lewandowski Family

GLADYS BAYLY KENNEDY, DESCENDANT

by Barbara Scrivens

Lady did not like to carry five-year-old Gladys Bayly to school. She did not like bridles, and she did not like the sack Gladys put on her back.

Before the “half-wild” Shetland pony became Gladys’s means of getting to and from the Otaorora Road School, on the back blocks east of Inglewood, the neighbour’s sons had ridden her bareback, and without a bridle.

“It was two miles to school on a road that wasn’t tar-sealed—all the roads around there were gravel then—and I’d have to coax her to get me to school. She’d go on for a while, then all of a sudden, she would turn round round and round, and try to buck me off, because she didn’t want to have anyone on her back—and especially not with a sack like I used, because we didn’t have a saddle.”

One morning, Gladys met the reluctant Lady’s former owner on his way to another property with some of his other horses.

“Lady wanted to turn back and go with those other horses to where she used to live. Mr Watson said to me, ‘Hang on Gladys.’ I had my lunchbag, a little schoolbag thing over my shoulder, and I didn’t know what he was doing, but he must have been going haymaking because he had a pitchfork. I assumed that he gave her a dig with it, because she never stopped—not once—all the way to school.”

Gladys, the fifth of Josephine (Josie) and Howard Bayly’s six children, was born on 21 May 1929, 17 years after her eldest sister, Phyllis. Her mother was the youngest of Matthaeus1 and Josephina Lewandowski’s eight children.

Matthaeus and Josephina arrived in New Zealand in 1876 with two-year-old Johann (John), Margaret Mary, who was born at sea, and Matthaeus’ 14-year-old sister Marianna. The Lewandowskis settled in Taranaki in December 1878, after more than two years’ in Hokitika.

Gladys, growing up on the Bayly family farm, gave no thought to the Polish side of her family.

“We knew we were Polish, because we found out that our mother’s maiden name was Lewandowski. We used to say to her, ‘What a funny name,’ because our name was Bayly. She didn’t say anything, but she must have taught my father some Polish, because she used to talk to him in Polish, and he used to talk back to her. Sometimes, if she got angry with us when we did something naughty, she’d say something in Polish. We used to say, ‘What are you talking about?’ but she never ever told us, and she never talked to us about anything Polish.

“It was after my mother died, in 1965, that I became interested. There were was lot of reunions going on in Inglewood—Polish families getting together—and people were talking. I used to work in Inglewood, and used to know a lot of Polish families. I’d hear all these names ending in ‘ski,’ and I’d think, ‘Oh, that’s like our mother’s name,’ and it dawned on me that I was half-Polish. It hadn’t struck me before. As the years have gone on, I’m thinking about it more and more, and loving what Barbara [McCracken] found about our roots.2 We just knew that our grandparents came to New Zealand. We had no idea of what all those people must have suffered when they came here, and how hard it must have been for them.”

Matthaeus Lewandowski, died at his home in Olivia Street, Stratford, six years before Gladys was born, but she vaguely remembers her maternal grandmother, Josephina, née Meller, who died in November 1932, after whom her mother was named, and whose name later passed to Gladys.

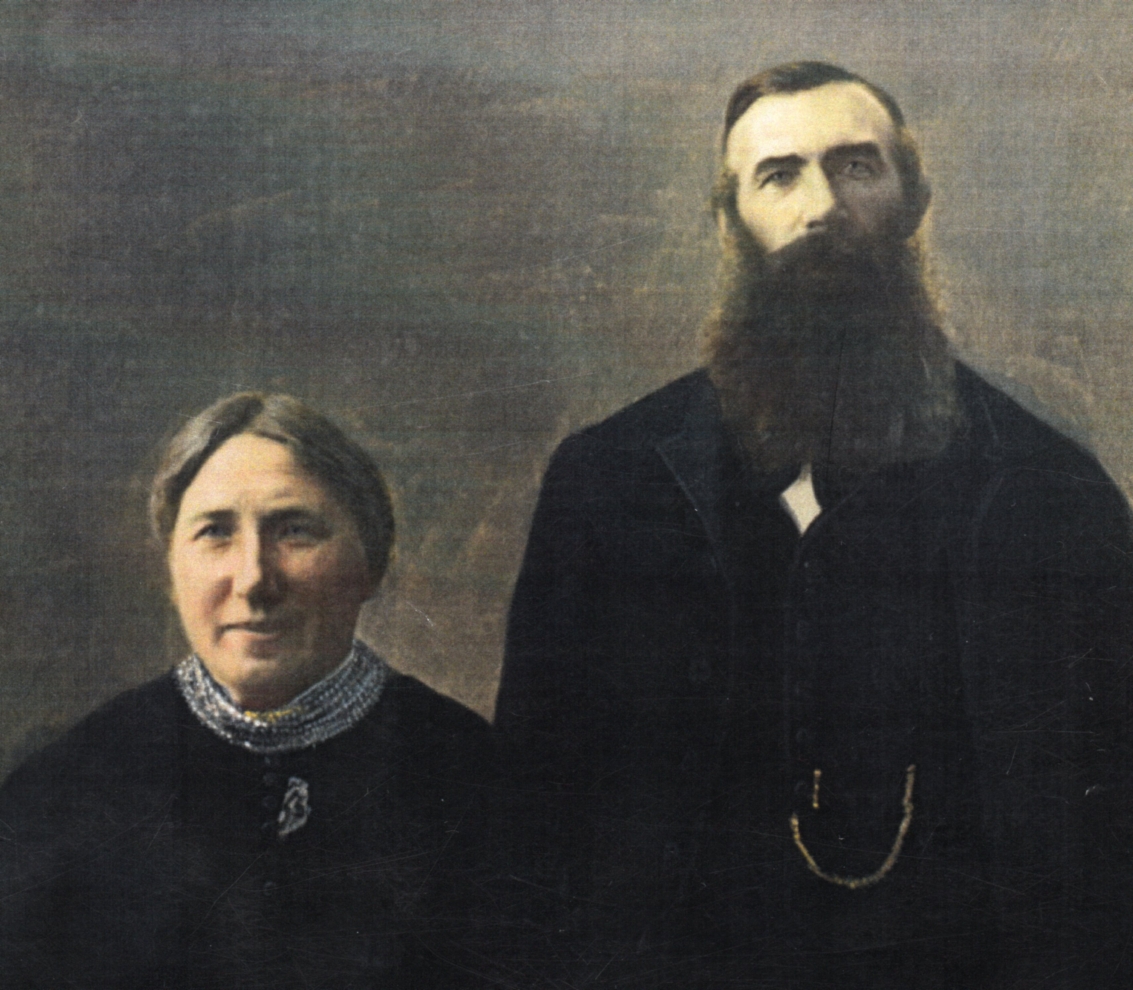

Josephina and Matthaeus Lewandowski.

“You know you sometimes have an imaginary figure you dream about? Well, I went to this place in Stratford with my mother, and this lady in a long black dress and white hair was going around making sure that everyone had plenty to eat. There was all this food on the table, and she was saying, ‘There’s plenty to eat.’ I still cling to the idea that it was her, and that it wasn’t a dream.”

In the years immediately before her death, Josephina had seven daughters living nearby, and 52 grandchildren,3 and food-laden tables have always been compulsory at Polish get-togethers.

Josephine Pauline was born 13 years after her only brother, and 11 years after her eldest sister, known to Gladys as Aunty May Bottin, and who, as Maria Lewandowska, was among several born on the fritz reuter, on its 110-day voyage from Hamburg to Wellington in 1876. One adult, six children and four infants died on the journey.

For Josephina to have embarked heavily pregnant on what she and her husband knew was going to be an arduous journey—Poles had been emigrating from their Prussian-partitioned homeland since 1872—their situation must have been grave.

_______________

Otto von Bismarck… sought to squeeze out any semblance of Polish culture from the society, including its deeply entrenched Catholic faith.

According to the fritz reuter passenger list, 18 families, two single women and two brothers aged six and two, originated from the same village that the Lewandowski family had lived in for generations: Kokoszkowy, about three kilometres north of Starogard Gdański. The 81 people included 44 children.4

The Kokoszkowy families were recorded on the fritz reuter passenger list in this order: Alfuth, Rogucki, Rzoska, Kowalowski, Labowski, Turczyk, Meller, Lewandowski, Treder, Rzoska-Preufs, Mischewski, Chabowski, Kuklinski, Brzoska, two Fabich brothers, and Drzewicki.5

The story goes that the villagers had all owned small blocks of land. The men had worked for a more prosperous German land-owner in the area, and the women and older children tended the home-blocks, which provided staples such as vegetables, fruit, poultry, and sometimes a cow or pigs.

As the Prussian-partitioning of Poland from 1795 extended into the second half of the 19th century, the political situation for Poles refusing to bow to German rule worsened. Prussian officials had already germanised names of Polish towns and villages. They then ordered priests to germanise Polish names in church records: Christian names of Polish children they baptised, and surnames of Polish people they married. From 1862, Otto von Bismarck, in his drive to create a massive German Empire, sought to squeeze out any semblance of Polish culture from the society, including its deeply entrenched Catholic faith.

Wealthier, well-educated urban Poles seemed to cope better; they spoke several languages and had the choice of moving temporarily to other parts of Europe. Rural Poles who refused to bow to the germanisation found it increasingly harder to survive. Their stubborn opposition to the demise of Polish-language schools led to their turning their backs on the available German-language schools, and any formal education for their children. One educated generation could teach the next, but with Polish books illegal, by the third or fourth generation, the majority of the Poles left in villages like Kokoszkowy were illiterate.

At the same time, the Prussians devised a cunning military reserve system, which “touched every family and community within the Prussian state,”6 a response to the Prussian defeat in France in 1806. The Prussian military conscripted all men aged 20 for three years, and organised the conscription in such a way that the men were 39 by the time had fulfilled their duties to the Prussian state.7 Germans embraced the system; Poles felt affronted that they should serve in an enemy’s military.

… the German refused to return their land deeds, and the Poles’ already precarious existences worsened.

It is inconceivable that the reserve system had not already enmeshed at least some of Kokoszkowy’s Polish men at the time of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. The knowledge that Poles were fighting on the French side made fighting for their Prussian oppressors even more galling. Young men like Matthaeus Lewandowski, 22 in 1870, had no choice. Then in the middle of his initial military service, he fought in the war, but before he left, married Josephina Meller, on 22 May 1870.

Stories from various Kokoszkowy families that immigrated to New Zealand have a common thread: The German landowner for whom they worked told them that he had the ability to arrange military exemptions from the Franco-Prussian War, if they grew food for the army: all they had to do was hand their land deeds to him for ‘safe-keeping.’ The Poles did as the German said but, once the war had been won, the German refused to return their land deeds, and the Poles’ already precarious existences worsened.

They were ripe for the German immigration agents whom the New Zealand colony sent to Europe to entice labourers, under its 1870 Immigration and Public Works Act, to help the first British landowners develop their farms, and build the first basic national infrastructure. (See polish anchors 1872-1876 for a fuller explanation.)

It seemed to be a win-win-win situation: the German immigration officials were paid for each family they sent to New Zealand; the German Empire was happy to get rid of the Catholic Poles; the Poles had nothing more to lose.

It is safe to assume the Poles had no knowledge of the existence of the New Zealand colony before its advertising campaign in Europe. Some families believed they were joining relatives in America.

Although fortunate to have been able to leave Prussia, the fritz reuter Poles faced other types of adversity in New Zealand.

Firstly, thanks to others’ shenanigans, they were not considered immigrants; none had paid passage and New Zealand officials would not let the passengers disembark until an agreement had been reached between the new colony and the German Consul to New Zealand, then FA Krull.

Secondly, apart from the single men and women, many potential British employers did not want to deal with continental Europeans. Their reasoning was that they did not speak English and had large families, but the single Poles did not speak English either, and immigrants from Britain also arrived with large families, so one has to factor in the new British colony’s general prejudice against anyone who arrived without a British background.

Thirdly, the much-vaunted 1870s immigration scheme had run out of money and any clear plans, and immigration officials placed non-English speakers into the most challenging areas in New Zealand. (See jackson’s bay 1874-1879.)

_______________

Once German Consul Krull paid the New Zealand colonial government to settle the fritz reuter ‘immigration’8 issue, the passengers disembarked. It is not clear what kind of information the new immigrants received, or what they understood about their options, but they knew they needed jobs to survive.

As usual, the single men and women found jobs easily, no matter their lack of English. The ship’s doctor selected 40 to 50 “very sizeable families,” including at least eight Polish ones, to fulfil a contract for labourers needed in what was then known as the Manchester block in the Fielding area.

Some of the fritz reuter Poles caught the steamer to New Plymouth, where roads, bridges and railways needed to be cut through the bush east of Mount Taranaki, to join New Plymouth with the southern coast.

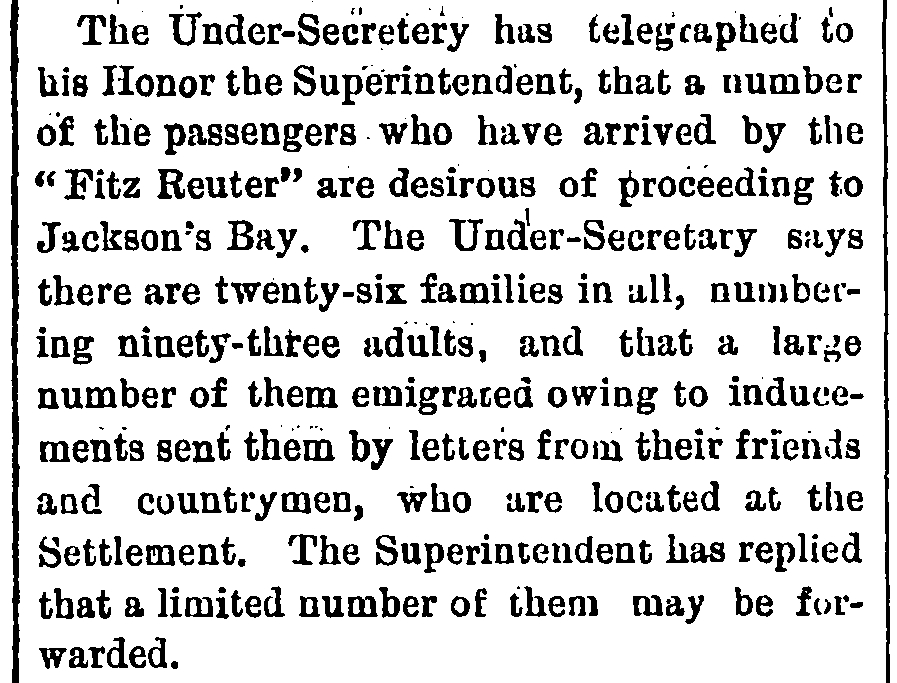

The Kokoszkowy Poles chose to remain together, and were posted to the West Coast. The west coast times, in its summary of Wednesday, 6 September 1876, printed:9

Only two fritz reuter families settled in the ill-fated “Special Settlement” of Jackson’s Bay: those of Franz Kurowski and Robert Lipinski. Months earlier, several Polish immigrants from the shakespeare had already refused to go there because of residents’ warnings of the appalling conditions, so the Under-Secretary was either misinformed or being disingenuous regarding “inducements.” Polish settlers in Jackson’s Bay wanted to leave, not encourage others to join them.

Nevertheless, the article suggests that at nearly a fifth of the passengers from the fritz reuter headed towards Hokitika, the West Coast’s main port.

Hokitika’s Immigration Officer, FA Learmonth, first advertised in the west coast times that the fritz reuter labourers were “open for engagement” on 11 October 1876, two months after they had left the ship in Wellington. The advertisement was still appearing on 6 November.10

According to the manawatu times on 5 October 1876, some of the families did get temporary employment, but bad weather “caused little demand for labour,” they had been without work for weeks, had no means of “subsistence,” and had written to the Minister for Public Works.11

Westland’s superintendent, James Bonar, was unmoved by the plight of the Poles (erroneously referred to as German) who approached him in January 1877 about finding work.

Once Bonar established that they had arrived on the fritz reuter, he said that, because they had refused to go to their “intended destination”—Jackson’s Bay—where the government had been “prepared to provide them with payable employment,” he had “nothing more in his power to give them.” (Bonar had championed the Jackson’s Bay project, but he did not receive the central government help he had hoped, or had been promised. A year earlier, he had chaired a commission of enquiry into the reason the shakespeare Poles had refused to go there.

The government finally acknowledged to wretched situation at Jackson’s Bay in December 1878, and shipped 20 adults and 25 children to New Plymouth via the stella, which stopped at Hokitika to pick up a further 46 Poles, including the Lewandowskis.12 They arrived in New Plymouth at 7pm on 19 December 1878, Josephina again heavily pregnant.

_______________

The first Poles in Taranaki arrived at the beginning of New Plymouth’s push to build their own botanical gardens and park on 35 acres of swamp and gorse-covered wasteland. Many of the Poles who stayed in New Plymouth took up jobs clearing and re-moulding the area, later named Pukekura Park. Other Poles gravitated inland to Inglewood. Before they could build the necessary roads and railways, the dense bush and its enormous trees had to be cleared and felled, and many of the Polish settler men started their working lives in New Zealand by leaving their families for days at a time while they camped among the trees where they worked.

The family book states that Matthaeus worked “long hours in very difficult conditions to provide for his family” in Inglewood.

Kate Lewandowski was born in February 1879 in Inglewood, but by the time Mary arrived in October the following year, the family had moved to Denbigh Road in Midhirst, where Matthaeus worked on a farm. By 1882, he had bought 61 acres on the other side of the main road, 6 Cross Road, valued, at ₤139.13 The family believes he had help from Newton King, a local businessman with whom he had become “quite friendly.”

The Lewandowski farm at then 6 Cross Road, Midhirst. The house had four bedrooms, a lounge and kitchen but no running water. The toilet and wash-house with its copper kettle were outside.

Anna Lena (Annie), Johanna Mary (Judy), Elizabeth Mary (Lizzie) and Gladys’s mother, Josie, were born at the Cross Road farm in 1882, 1884, 1886 and 1887. By the time Josie was a few years old, her older brother and sisters had left home. Margaret Mary returned when she married Peter Bottin and they moved back to manage the farm.

“From what I gather, my mother seemed to stay quite a bit with her older sisters; they would have been married, and she went to Stanley Road school, somewhere around Midhirst. She probably spent more time with her older siblings than with her parents.”

Gladys remembers the Lewandowski sisters as musically talented, so they would no doubt have performed at their father’s naturalisation celebration in 1905: Here, Josie is sitting in front, Johanna is at the back, Margaret Bottin is holding the violin and Annie Knox the button accordion. Josie played the violin and piano.

“My mother was very close to my aunty Mary, Mrs Wilmshurst, and aunty May, Mrs Bottin. Some years ago, after I was married, there was a reunion, something to do with the Lewandowski family. My eldest sister, Phyllis, Mrs Hurlstone, and I went to it. I met a cousin, who I’d never known before, a Mrs [Mary Louisa] Isbister. She was a Knox, 90 years old. I said it was a pity we didn’t have any photos of the whole family and she said, ‘I’ve got a little photo at home, a little wee photo, I’ll send it to you in the post.’ I said, ‘Oh, that’s something very special. Do you want to send that?’ She said, ‘Yes, you can take a copy of it and send it back to me.’ She didn’t know me from a bar of soap, and to trust me like that was wonderful of her.”

Gladys treasures the copies of the paintings and photographs someone “found in a suitcase under a bed” and distributed among family members.

“One was a painting of my grandparents. When they showed it to me, those great big photos, I just cried. How they never got burnt or something like that, I don’t know.”

The Lewandowsksi family in 1905, commemorating Matthaeus’s naturalisation on 19 October that year. From left, back: John, Judy, Annie Knox, Kate Kowalewski, Mary Wilmshurst and Lizzie. Seated from left: Margaret Bottin, Josephina, Matthaeus and Josie, later Bayly.

“Matthaeus must have been a good farmer. The newspaper talked about a large attendance at his clearing sale in 1913. His stock was in good condition and sold quickly at high prices.”

After Matthaeus retired from dairying in July 1913, he and Josephina stayed on the farm until they moved to Olivia Street in Stratford in 1916. Despite Matthaeus’s naturalisation, a year after their move to Stratford, the New Zealand government added the then 67-year-old to its Alien Register, which described him as born in Prussian Poland and having lived in New Zealand for 40 years.

Mathias and Josephine Levandoski are buried together at Stratford’s Kopuatama Cemetery.

Josie Bayly, youngest child, had a “beautiful, happy disposition” who mothered her son and five daughters with joy and gentleness, and perfected her own light touch with baking.

“She was a wonderful cook and made beautiful pastries and apple pies from her own butter, and the most fantastic sponges filled with homemade jam and thick cream.

“She could turn her hand to anything, and used to make her own laundry soap. She had an old hand-turned Singer sewing machine and sewed full-length dresses for Fay and me to wear at dances when we were teenagers. During the Depression, she sewed boys’ trousers, and lined them with flour bags. When the curtains faded, she used the pink covers of the auckland weekly news to make dye, and used that to brighten the curtains.”15

Doris Thompson’s return to New Zealand for a holiday in the 1960s prompted this photograph of Josie and Howard Bayly with all their children. From left, Doris, Mavis Kenny, Sid Bayly, Phyllis Hurlstone, Fay George and Gladys Kennedy. Doris married an American marine in 1944 and moved to North Carolina.

“My mother and father kept wonderful flower and vegetable gardens. My mother always had a huge row of sweet peas that the grandchildren loved to pick and make posies for her.”

Josie Lewandowski Bayly died two years after her husband. They are buried in the Inglewood cemetery.

Gladys married Michael Kennedy in 1955. They had five children: Diane, Michael, Wayne, Jane, and Alison, who died of cancer in 2000, four months after giving birth to her second daughter. Gladys’s husband, Michael, died in 2008 and she still lives in the family home in New Plymouth.

Some of her mother’s traditions continue with Gladys. A tray of sprouting sweet peas sat in the sun near the back door when I first visited her in April 2018.

“I will have to plant them out shortly, so they can overwinter. They don’t grow much over the winter, but they’re there for the spring.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2019.

APART FROM THE FIRST, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS ARE FROM THE LEWANDOWSKI-BAYLY COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE TAKAPUNA BRANCH OF AUCKLAND LIBRARIES FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Although Matthaeus’ name is spelt several different ways; on the Fritz Reuter passenger list, and various New Zealand documents, for clarity, I have kept the spelling that is on his Kokoszkowy wedding record, and both parents’ death records.

- 2 - McCracken, Barbara & Ivan, The Lewandowski Story; from Kokoszkowy to Taranaki, 2014.

- 3 - Ibid.

- 4 - Information taken from the original Fritz Reuter passenger list. The writing is a scrawl and not always legible, but the column showing the place people came from can be followed.

- 5 - Ibid.

- 6 - Gray, Wilbur E, Prussia and the Evolution of the Reserve Army: A Forgotten Lesson of History, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, page 9, 1920.

- 7 - Ibid, page 10.

- 8 - Although the Fritz Reuter passenger numbers do appear in some 1876 bookkeeping lists of immigrants—one shows that none of its passengers paid for their passage—the passengers still do not seem to appear in official lists of immigrants to New Zealand.

- 9 - https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/west-coast-times/1876/09/06/2

- 10 - https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WCT18761012.2.16.2

- 11 - https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WCT18761005.2.4

- 12 - Taranaki Herald 19 December 1878, page 2, IMMIGRANTS FOR TARANAKI

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18781219.2.10 - 13 - A Return of the Freeholders of New Zealand, October 1882. On page 23 of the L-section, his name is spelt Mathias Lewandrosky, farmer.

- 14 - Hawera and Normanby Star, 29 July, 1913, page 8,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HNS19130729.2.67.6

And, on 16 August 1913, page 3,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HNS19130816.2.7.2 - 15 - That particular quote from Gladys is from the Lewandowski family book compiled by Barbara & Ivan McCracken, pages 90 & 91.

If you would like to comment on this or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org.