Catharina Grabowska Salter

IT TOOK A VILLAGE

by Barbara Scrivens

Degrees of separation did not feature in the villages of 1800s north-western Poland. Petty differences that tend to emerge among people in more peaceful times, dissolved before the bigger problems that Poles faced under Prussian-partitioning.

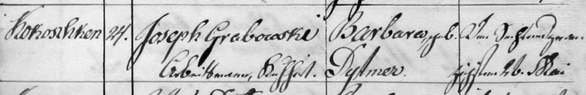

Catharina Grabowska was born into one such village—Kokoszkowy—at the beginning of a cholera epidemic that swept through continental Europe from 1865 to 1875. Her father, Joseph Grabowski, died aged 34 just two months after she was born on 26 May 1867. Her mother, Barbara née Dytmer Grabowska, died slightly more than four years later.

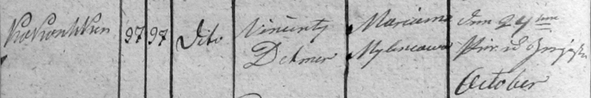

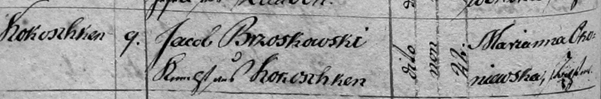

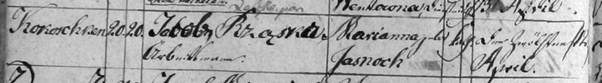

Catharina Grabowska’s birth record, in German script and a mixture of Polish and German spellings. The top image is the left-hand side of the record book, and the bottom is the right-hand side. It is not clear whether Catharina’s godmother, Catharina Dytmer was a direct maternal relative, or a Dytmer through marriage.

By the time Catharina Grabowska was born, Poland had been geographically extinct for more than 80 years. Rural Poles of all ethnicities had lost even the smallest pieces of land, and their ability to supplement a labourer’s meagre income. Under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s 1871 plan to unify Germany, Polish inhabitants in villages such as Kokoszkowy found it increasingly tough to cling onto their language, culture, and religion—all things that Bismarck despised and planned to obliterate.

Stories of Polish children being punished for speaking Polish in class give a clue to why so many of the Poles who arrived in New Zealand in the 1870s and 1880s were illiterate. Polish schools had been banned, and Polish parents often refused to send their children to German schools.

The Poles were not the only Europeans facing economic and political persecution. By the 1870s, several million people saw opportunities in new lands and left. The United States of America was a preferred option for many—promising the most—and some passengers embarking on ships bound for New Zealand had the impression they were bound for a shorter journey than the three-month sea voyage to New Zealand.

Catharina arrived in New Zealand as an eight-year-old on the fritz reuter, listed on its 1876 passenger list as the daughter of Jacob and Maria Rzonska, whose own surname did not match their real one. Jacob’s and Maria’s taking on the orphaned Catharina was an altruistic gesture repeated by several of the Polish families that left the Kokoszkowy area at the same time. Her identity may never have been identified had it not been for her marriage in Carterton in 1883.

Her marriage certificate states that Katie Grabowsky, a servant girl aged 15, married Thomas Salter, a farmer aged 25, at the St Mary’s Catholic church in Carterton. That church was the first of several churches initiated and built through the Polish priest Father Anthony Halbwachs, who officiated at the marriage ceremony. Father Halbwachs was posted to New Zealand in 1878 and settled first in Carterton where his Catholic parish consisted mainly of 150 Poles off the fritz reuter and the earlier terpsichore.

Father Halbwachs did not fill out the marriage certificate—his name is misspelt. Katie’s birthplace is stated as Polish Prussia, her father as Joseph Grabowsky, labourer, and her mother as Bella Oudeman. Two of the witnesses at the wedding were Frank Lipinski and Jacob Broska. The latter was the same Jacob assumed to be Catharina’s father on the fritz reuter.

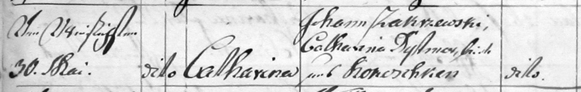

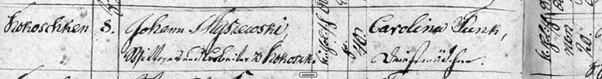

The 1857 marriage record of Joseph Grabowski (25) and Barbara Dytmer (22). Barbara’s older brother, Anton, was one of the witnesses.

The tangle of Katie Grabowsky’s origins is an example of how tough it is to explore the Polish roots of settlers who arrived in New Zealand in the days when records were created from mostly illiterate people whose language challenged the colonial record takers, who themselves often had equally challenging handwriting.

_______________

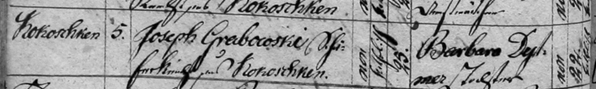

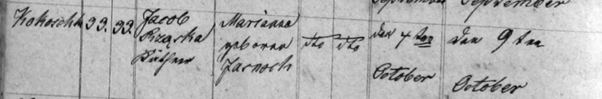

Joseph Grabowski’s 1867 death record in Kokoszkowy shows he left a widow and three minor children. Catharina was his and Barbara née Dytmer Grabowska’s fourth child. Their first son, Vincent, probably named after Barbara’s father Vincenty, died aged 14 months in 1860. As well as baby Catharina, the widow Barbara Grabowska was left with Johann, aged six, and Marianna Julianna, aged three.

The death of a spouse in the impoverished societies that the Poles under Prussian rule lived in those days meant the end of either an income or a caregiver, so it is not surprising that 14 months after Joseph Gratkowski died, Barbara, then 34, remarried—to 24-year-old Vincent Arim.

That marriage produced two children. Seven-month-old Matheus Arim died in May 1871, and a Matheus Michael Arim was born in September that same year. Possibly to make sure that the two boys were not confused with each other, a note on the latter’s birth record indicates a sibling who had died.

Barbara Arim died four months to the day after Matheus Michael Arim was born. Her death records her only as the wife of Vincent Arim, aged 36 years two months and 24 days, which happens to coincide with the birth of Barbara née Dytmer Grabowska.

Like her first husband, her death record states that she left three minor children. But which three children? Could Johann, then 11, be classified as an adult? Marianna Julianna would have been eight when her mother died, Catharina four, and their surviving half-brother four months. Kokoszkowy records don’t seem to show any of them dying before their mother, but one can surmise that after her first husband’s death, a Dytmer or Grabowski family member, or a close friend, may have taken in one of the children.

_______________

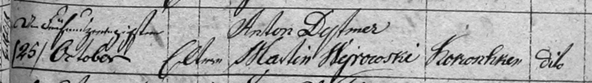

According to their 1825 Kokoszkowy marriage record, Barbara née Dytmer Grabowska Arim’s parents were Vincenty Detmer and Marianna Milencowa. Over the years, different hands spelt the name another three ways: Ditmer, Dittmer, and Dettmer.

The 1835 birth record of Catharina Grabowska’s mother, Barbara, showing her maternal grandparents, Vincenty Detmer and Marianna Milencowa, whose name is clearer in other children’s birth records.

Catharina’s mother, Barbara Dytmer, had at least four older brothers, Johann, Jacob, Antoni and Ignatius, and a younger sister, Marianna. Two of the brothers had growing families by the time Barbara married Joseph Grabowski. Marianna married Johann Myszewski in 1839, and by the time she died in 1873, she had had at least five children. The last, Lucia, lived for six days, and died of an “unknown” reason.

On the same page as baby Lucia are the names of her maternal uncle Anton Detmer and her mother. Anton died of cholera in August 1873, leaving his widow Barbara née Wróblewska with seven minor children. Marianna née Dytmer Myszewska died of cholera complicated with typhus and left her husband with four children, Julianna (13), Jacob (10), another Catharina (6), and Joseph (3).

Johann Myszewski (40) married Karolina Funk (20) six weeks after his first wife’s death, and was also aboard the fritz reuter in 1876, with his surviving children—Catharina Grabowska’s cousins—two older nieces, his new wife, and their baby Francisca, who died of heat exhaustion on the ship.

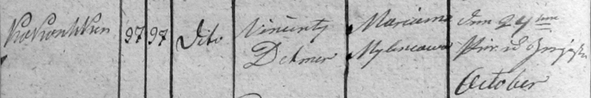

Johann Myszewski’s second marriage, to Carolina Funk in 1873, shows his brother-in-law Jacob Dittmer as a witness.

_______________

Of the 57 Polish families who arrived aboard the fritz reuter in 1876, 20 of the couples had been married in the ancient village church of St Barbara’s, at least 60 people had been born in Kokoszkowy itself, and 17 in its immediate environs.

Surnames repeat themselves in church records, as do Christian names. As the records get younger, the germanisation of their Polish names becomes more apparent.

Surnames linked to the Grabowski-Dytmer union and its extensions include Brzoskowski, Jasnoch, Lewandowski, Meller, Myszewski, Okoniewski, Rząski, and Wróblewski. Boys’ names like Jacob, Johann, Joseph, and Vincent were the most popular, and girls were often named Anna, Barbara, Catharina, Julianna, or Marianna.

Catharina Grabowska’s maternal grandfather, Vincenty, had at least two siblings alive when his mother, Marianna Dytmer senior, died in 1872: Stephan and Barbara, who married Jacob Rząska in 1837. They had a son Johann in 1840, who happened to marry Barbara Preiss. That couple were also aboard the fritz reuter in 1876, with their daughter, Marianna (4), and Barbara’s orphaned nephews Franz (7) and Paul (2) Preiss.

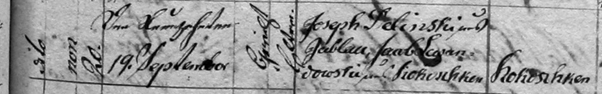

I questioned why Jacob and Maria Rzonska (not connected to the Rząska family above) would be responsible for Catharina Grabowska when there seemed to be closer family members. The link came through Maria. She turned out to be Marianna Okoniewska, who married Jacob Brzoskowski in Kokoszkowy on 19 September 1869. She was 20. He was 22. Marianna Okoniewska had a brother, Anton, who had married a Marianna Grabowska in 1858. Jacob and Marianna became known as Brzoska in New Zealand, but there is no denying that the name started off as Brzoskowski.

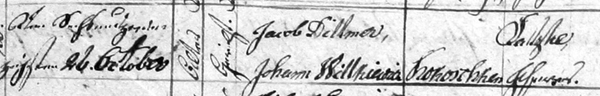

The 1869 marriage record of Jacob Brzoskowski (22) and Marianna Okoniewska (20).

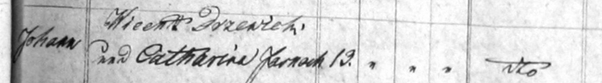

Jacob and Marianna Brzoskowski’s first child, Michael, was born in 1870, and died aged four months. Their second child, Francisca, died aged five months in February 1872—10 days after Catharina’s mother died. Perhaps Catharina’s stepfather, Vincent Arim, in his own desperate situation as a newly widowed father and stepfather, made a gesture to the bereaved Brzoskowski parents, and offered one of his dead wife’s children as a replacement. Or one of Catharina’s many relatives suggested it. We can only speculate because then, a village under so many other stresses seemed to act in accord. Whether Ignaz and Leo were born to Jacob and Marianna Brzoskowski before or after they took on Catharina is not known.

The hand-written passenger list on the fritz reuter shows three Rzonska families. Why Jacob and Marianna Brzoskowski and three children were listed as Rzonska remains a mystery. A family story suggests that they took on a Brzoska identity to get onto the ship, but that makes no sense unless the family that gave them the Rzonska identity happened to have children who could pass as the same sexes and ages.

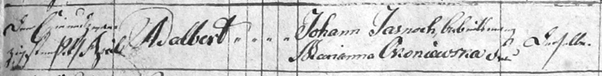

The misspelling of the name Rząska is easier to understand, as the diacritic “a” can be heard as “awn” or “on.” The brothers Johann and Albert (Adalbert) Rząska’s birth records below show clearly that diacritic “a.”

Johann Rząska’s 1842 birth record, showing his mother was a Jasnoch.

Albert Rząska’s 1849 birth record. Marianna Rząska was born between Johan and Albert, but the script on her 1846 birth record is less clear.

Alphabetical lists of passengers do a disservice to those passengers’ relationships with other families. Human nature decrees that people naturally gravitate to those they know, and in a bustling port like Hamburg, where the fritz reuter left from, there is no doubt that families stuck together.

Each of the 515 people who boarded were allocated numbers, Albert and Francisca née Gajkowska Rząska 104 and 105. Johann and Barbara née Preiss Rząska and their daughter were 317 to 319. The Preiss brothers they kept with them were 320 and 321. Immediately before Johann Rząska’s family, his younger sister, Marianna née Rząska Treder, embarked with her husband Joseph and their four children and took numbers 311 to 316. The extended Myszewski family boarded immediately after Johan Rząska’s family, with numbers 322 to 330.

Another 91 people boarded before Jacob and Marianna Brzoskowski and their children, who were allocated numbers 413 to 417.

_______________

Aboard the fritz reuter, eight-year-old Catharina Grabowska was orphaned, but not alone. She may never have reached New Zealand, as her guardians apparently were among those who boarded the ship on the understanding that it was headed towards the USA.

In New Zealand, Jacob Brzoskowski continued to use the shortened version of his name. The shorter one was still a challenge for colonial record takers—he was naturalised in Masterton as Jacob Broyska. Even today, New Zealanders regularly mispronounce the “kow” within a Polish name. (It is not “cow” but “kov” or “cough.”) Jacob and Marianna Brzoska had 11 more children in New Zealand, and in 1901 moved with the bulk of them to Buffalo, New York.

By the time the Brzoska family left New Zealand in 1901, Catherine and Thomas Salter had at least six children: Katherine Mary, Emily Mary, George Thomas, Eliza, Thomas John, and William. Charles was born in 1903. They lived in the Wairarapa. Catherine Salter showed her support for women’s suffrage by enrolling to vote in the 1893 election—the world’s first for women. She was described as a “married woman” living in Masterton and residing in Mangamahoe.

One American Brzoska family researcher, who followed Jacob and Marianna Brzoska’s time in New Zealand, could not find a Catharina thread and decided that “Katerina died before 1879 at about eleven or twelve years of age, a mystery child indeed.”

Another convinced herself that Barbara Dytmer was not her great-grandmother—she believed that the Bella Oudeman on Katie Grabowsky’s marriage certificate was her ancestor. But there seems to be no Oudemans in the Kokoszkowy church records—or in any Pomeranian area—and records show that Catharina’s father, Joseph Grabowski, married Barbara Dytmer on 24 October 1857.

The Bella Oudeman name can be explained in several ways: Birth, marriage and death certificates of that time were notorious for their inaccuracy. The record taker in nearby Masterton in 1901, for example, repeated the name Michael Gronkowski as the bride’s father as well as her mother, so he may have been more interested in filling the boxes rather than precision. Even if the marriage witnesses Frank Lipinski and Jacob Brzoska had been literate, and therefore be able to write down Catharina’s mother’s maiden name, they would not necessarily have known it, or, if they did, the transcriber may have misheard the Polish accent using the Polish diminutive “Basia” for “Barbara” and decided the closest English word was “Bella.”

The St Mary’s Catholic church in Carterton on its original site on Philip Street. A heritage plaque at the St Mary’s hall in King Street says that it was moved north “despite strong opposition” in 1904, and moved again in 1923. It is not clear what happened to the spire, which was removed when another church was built. The church shell became a hall.

There is much we will never know about the 15-year-old Katie Grabowsky who married in 1883, but we do know that the ceremony was officiated by a Polish priest in a beautiful new Catholic church, among people she knew, in an atmosphere she was comfortable in, and in a language she understood. Carterton’s Polish community would have done what Poles always do at a wedding: gather, share food, drink, and dance into the night to the obligatory piano and button accordions and accompaniments.

Catherine Salter died in Wharepapa on 20 March 1942, aged 75. She left two adult daughters and four adult sons, and a death certificate that was still inaccurate: She was not born in Warsaw, and was not 18 when she married. She is buried at the Taumaruniu cemetery alongside her husband, who died in 1938.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2022

THANKS TO: Ray Watembach, president of the Polish Genealogical Society, who introduced me to the riddle of one of his distant relatives, Catharina Grabowska, and shared his research into her family. His notes, and lists of births, marriages, and deaths in the Kokoszkowy region, provided the foundation to this story.

THANKS TO: Don Hansen, a member of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists, who confirmed my on-line question regarding the causes of death of the baby Lucia Myszewska, her mother and her uncle.

PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDIT: Catholic Church, Carterton, New Zealand, by Burton Brothers. Te Papa (C.013220)