THE CONUNDRUM OF NATIONALITY

by Barbara Scrivens

An island nation like New Zealand has no problem defining borders. One is either on land or in the sea.

It is not that simple for a country like Poland, where boundaries have been changing from the moment Slavic tribes decided in the sixth century to settle between the Odra (Oder) and Wisła (Vistula) rivers.

According to Polish legend, three Slavic brothers, accompanied by their families and followers, happened to be travelling between those rivers. One of the brothers, Lech, saw an eagle guarding a nest high in an old oak tree. The huge bird looked so proud and majestic that he took it as a sign to stop.

He instructed his people to start building permanent structures, and called the settlement Gniezno, derived from the Polish word for nest, gniazdo. A white eagle become the Lechites’ symbol, and was emblazoned on their banners and coats of arms.

One of the many white eagle sculptures scattered around Warsaw, this is one of a pair that guards gates on the Krakowskie Przedmieście.

Legends are, by their narrative nature, prone to being tweaked by consecutive story tellers. The Museum of Independence in Warsaw presents another two variations, below. The first comes from a chronicle of the 13th to 14th centuries, which does not mention an eagle, and the second from the 15th century historiographer Jan Długosz, who puts the eagle in the role of affirming Lech’s decision rather than causing it:

… and when Lech with his progeny travelled through vast forests, where now the Polish kingdom stands, after arriving at a certain charming place… he pitched his tents. Willing to establish his first settlement there… he said: “Lets build a nest!” This is why the place is called Gniezno up to this day…1

… for it is there that the first prince and the father of Poles, Lech, after setting a camp, aborted being a nomad and decided that this is where a nest could be for him and the elders, and this is where his ducal residence, for him to settle for good, would be built. This is also where he found an eagle nest in high and magnificent trees…2

While the sea crashed around New Zealand’s predominantly rocky shorelines as it waited for discovery, on the plains of central Europe the first inhabitants formed family groups and cliques that eventually became separate communities with linguistic and cultural differences.

By the ninth century, some of the original Slavs moved south to the Balkan Peninsula and others east towards Russia and Asia. The rest, known as the West Slavs, remained in Europe. German expansion assimilated the Lusatians and Veletians. Czechs and Moravians formed the first Czech Kingdom. The Slovaks aligned themselves to the Hungarian Kingdom. The Polanie (Polans), Wislanie (Vistulans), Pomorzanie (Pomeranians) and Mazowszanie (Mazovians) settled on the flat, fertile land and formed the first Polish state.3

The Piast dynasty emerged. Polish schoolchildren are taught that Siemowit Piast ruled the first Polish tribes, that Lestek succeeded him, and that Siemowit’s father was already a farmer in Gniezno.4 Lestek was born around 880, so the family had seen many generations live and die in the region since Lech’s decision to settle there.

An 1893 drawing of Siemowit Piast, legendary duke of the Polans.

The artist was Walery Eljasz-Radzikowski (1841-1905).5

The later Piasts took on successive titles of dukes of Polans, and spread their control and influence over neighbouring tribes. When Lestek’s grandson, Mieszko I, accepted the title in 960, he continued his father’s and grandfather’s work in uniting the tribes and extending the Piast influence beyond their original boundaries. Mieszko I’s armies clashed with those of other European states competing for land. His men were not always victorious in battles, which may have been the reason why he used his position to engage in dialogue rather than conflict with his neighbours.

Mieszko I forged diplomatic relations with a Christian neighbour, the Bohemian prince Bolesław, by marrying his daughter Dobrawa in 965. After Dobrawa died in 977, Mieszko I married Oda of Haldensleben, a daughter of a German margrave,6 who introduced him to Saxon aristocracy.

The year 966 remains undisputed. The year after he married Dobrawa, Mieszko I accepted Christianity on behalf of his people, and was baptised. It is unclear how many of those people reciprocated his decision, or how quickly: One cannot assume that the pagan priests, for instance, were keen to share their powers with another religion.

This painting of Mieszko I after his baptism is by Jan Matejko (1838–1893).7

Mieszko I’s decision to be baptised was a politically shrewd move that gave him the backing of the powerful Pope, and Rome’s papal states, and elevated him and his followers from a declining pagan race to an accepted Christian one. It put them on a par with their Bohemian and German neighbours, whose leaders no longer considered the Piast duchy as one made up of tribes of barbarians.

One of the motifs commemorating Poland’s 1,000 years of Christianity. This one was made in Michigan, USA.

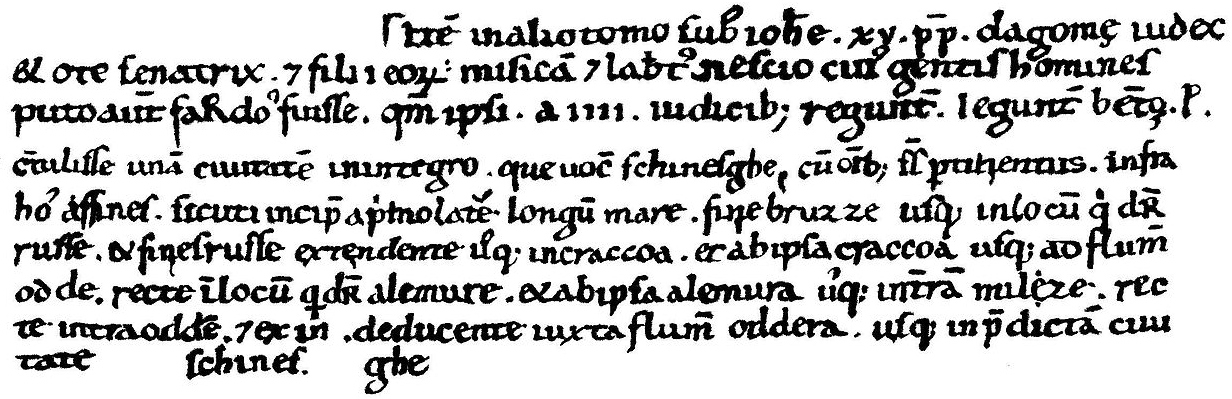

Mieszko I developed into a charismatic and wise ruler, and a talented military leader, who extended Poland’s8 boundaries, and transformed the state into one of the strongest powers in Europe. Before he died, he placed the Gniezno state under the protection of St Peter. The document, known as the dagome iudex, describes the area and its boundaries.

Part of the dagome iudex, believed to be copied by the Vatican circa 1087. The document describes the boundaries of the Polish state, but the transcriber did not seem to know from which “tribe” the people concerned came from.9

After Mieszko I’s death, his son with Dobrawa, known as Bolesław the Brave, led Poland through a war with Germany, and later with Rus, which extended the boundary as far east as Kiev. Bolesław’s battles along western and eastern borders ran alongside his active cultivation of relationships with other neighbouring states, such as Bohemia and Italy.

Shortly before he died in 1025, Bolesław was crowned—or crowned himself—king of Poland. the history of polish diplomacy:

We do not know whether this event was preceded by deputations to Rome, but it was probably not; Bolesław was likely of the opinion that this had been his right since 1000, given that he had an archbishop in his realm.10

Historical accounts vary, but if one takes the work of the academics who wrote the book above, one cannot take 1025 as the year that Poland became a kingdom: it refers to Bolesław the Brave’s grandson Kazimierz as a duke, and dukes wore ducal not kingly crowns.

Despite Mieszko I’s acceptance of Christianity, paganism simmered and erupted during the reign of his grandson, Mieszko II, who was deposed during a pagan rebellion in 1031 and restored as duke in 1034, during which time two of his brothers and another Piast leader tried, and failed, to rule.

Mieszko II’s son Kazimierz earned the title The Restorer through deeds such as granting land to his armed forces, and reconstructing the Church.11

Kazimierz’s son Bolesław II had himself crowned king of Poland in 1076, but the event did not prevent his having to flee the country after being deposed by his younger brother, Władysław Herman.12

Religious beliefs and differences, intertribal marriages and marriages and unions of cross-border convenience, deceptions, greed, rivalry, loyalty, political shenanigans, invasions, and counter-invasions—all created dynastic struggles, years of battles, and land gained and lost. Successive Piasts discovered Poland challenging to rule, but five Piast brothers did so for several years in independent duchies.

The meadows dominating north-central Europe—ideal for crops, building roads, and Polish expansion—remained a geographically unhindered conduit for plundering enemies from the east and west.

Polish armies were essential protection.

_______________

The last three Piast leaders were crowned legitimately. Przemysł II reigned for a year before he was assassinated in 1296. King Władysław I (Łokietek), crowned with the blessing of Pope John XXII in 1320, had ruled Poland as a High Duke since 1306. His son, King Kazimierz III, crowned in 1333, died without a male heir and was Poland’s last Piast monarch.

The Szczerbiec, the traditional coronation sword of Polish kings and apparently first used for the coronation of King Władysław I in 1320. It shares the same coat of arms as King Przemysł II, a white crowned eagle on a red background.13

In 1370, Kazimierz III’s nephew King Louis d’Anjou of Hungary added the Polish crown to his inheritances. King Louis’s eldest daughter died aged seven, so when Louis died in 1382, the Hungarian crown went to his second daughter, Mary. After two years’ assession negotiations between Polish nobles and King Louis’s widow, the Polish crown went to his youngest daughter, Jadwiga, then 10 years old.

As daughters of a king, the d’Anjou sisters’ marriages had been planned for them, and from the time she was a year old, Jadwiga had been betrothed to William of Austria, four years her senior. She still expected to marry him when she was crowned in 1384, but the young prince was unpopular with the Polish nobility, which still hankered for another Piast on the throne, and did not trust a 14-year-old foreigner to lead their country. They expelled William when he arrived in Poland to claim his bride.

Aged just 12 two years later, Jadwiga married 35-year-old Jogaila, Grand Duke of Lithuania. For the marriage and the Polish crown, the pagan Jogaila converted to Christianity, took the name Władysław II Jagiełło, and pledged to convert his pagan subjects in Lithuania. King Władysław II Jagiełło ruled Poland with Jadwiga until she died—soon after childbirth, aged 25—and ensured his continuing reign over Poland by marrying Kazmierz III’s granddaughter Anna.

Queen Jadwiga of Poland was famed for her mediation skills, her impartiality, and her

intelligence. She protected the poor, and made sure that new hospitals, schools, and churches were built. Her people

venerated her, and Pope John Paul II canonised her in 1997.

This likeness was painted by Marcello Bacciarelli (1731–1818).14

King Jagiełło’s reason for pursuing a partnership with Poland stemmed from his wanting to halt the Teutonic Knights’ crusades into Lithuania. Although he led and won several battles in his dual roles as ruler of both Poland and Lithuania, the pull of Lithuania may have inhibited him from becoming an assertive negotiator for Poland. He ruled Poland for 48 years, the longest of any monarch, and his dynasty lasted until his last successor died without an heir in 1572.

During their 186-year dynasty in Poland, the Jagełłonians continued to win and lose battles and negotiations with neighbours on all fronts. They amassed a great deal of land for Poland and Lithuania, but the management of that land was fraught.

The heirless successor, King Zygmunt II Augustus, agreed to the formation of a Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After he died in 1572, the nation’s nobility, the szlachta, introduced their preferred notion of electing a king rather than a ccepting one with blood ties to the Piast dynasty.

The wording on a display board at the Museum of Independence in Warsaw:

… after his death new rules of choosing a king must have been decided upon. They abolished the heredity of the throne, substituting it with royal election, which meant choosing a ruler from among the candidates seeking the Polish crown. The throne was taken by representatives of different European dynasties and Polish houses. During his reign, the ruler used the state coat of arms with his own coat, or the initials put on the breast of the White Eagle.

Several versions of this painting appear in various Polish museums. Its origin is unclear, but it is called noblemen in voivodship uniforms on the elective field.15

For two centuries from 1573, the sejm (parliament) elected the Polish king. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth became the largest country, and one of the greatest powers in Europe, with land that stretched across the Baltic States, past Kiev in the east, and south to the Black Sea. It was the commonwealth’s “Golden Age.” The noble minority governed. Latin was the official language. The joint state influenced European politics, trade, literature, and discovery.16

Non-Poles may not be familiar with the works of Mikołaj Rej (1505–1569), the first to write exclusively in Polish, or poets who followed, like Jan Kochanowski (1530–1584) and Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855). They are more likely to know Mikołaj Kopernik (Nicolaus Copernicus), the Renaissance astronomer and mathematician who shocked the world when he announced that the earth revolved around the sun.

A statue of Adam Mickiewicz in his own square on the southern bend of the Krakowskie Przedmieście park in Warsaw. Mickiewicz is best-known for his epic poem pan tadeusz.

Mikołaj Kopernik (Nicolaus Copernicus) immortalised in bronze in front of the Polish Academy

of Sciences, whose building was covered in scaffolding when this photograph was taken, hence out of shot. The building in the

background is the Zamoyski Palace.

Bertel Thorvaldsen designed the bronze in 1822, and it was completed in 1830.

As the years passed, the wars over territory n central and eastern Europe continued. The Poles gained a reputation for being fierce fighters and frightening to face, which they exploited through embellishments on their livery and horses.

By the 17th century the Polish-Lithuanian military had devised cunning tactics against the vast Turkish and Tartar forces. The Poles used highly mobile cavalry units to prise out weaknesses in their opponents and attacked with light cannon artillery and rocketry. Polish-Lithuanian general, military engineer and gunsmith, Kazimierz Siemienowicz, published his artis magnae artilleriae in 1650. It included designs for rockets and other pyrotechnic devices, and was the Polish army’s standard instruction manual for the next two centuries.

Despite the victories, constant war led to inevitable losses. A third of Poland’s citizens perished in conflicts with the Turks and Tartars in the second half of the 17th century.

External enemies had been made, but Poland’s own nobility consumed the commonwealth from within. The nobility made up the bulk of the Polish-Lithuanian military forces, but also made the country vulnerable.

The Polish monarchy and aristocracy had begun their destructive tangle back in the Jagełłonian era when in 1454, King Kazimierz IV (Casimir IV) needed the support of other nobles to go to war against the Teutonic Order. He persuaded the nobles to fight for him by offering to create a law that ensured no new taxes or military levies could be raised without their consent.

The resulting committee evolved into the parliament, or sejm. Within 40 years, its members granted themselves numerous privileges while restricting the rights of the peasants who made up most of the population.

The column and statue of Zygmunt III Waza, fourth elected king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, who moved its capital from Kraków to Warsaw. It was commissioned by his son and successor, Władysław IV Waza, to stand in the Castle Square, and first erected in 1644. The column has gone through many reconstructions, the latest after WW2.

The kingly stare from the top of the 22-metre column. One wonders whether the point of the statue was precisely its height above the mere mortals below.

As the nobles created a system of serfdom and economic advantage for themselves, the nonhereditary king’s role changed, and his powers reduced. They introduced a law that forceded any king-elect to swear to uphold the constitution and all the nobles’ privileges, and a strategy called a liberum veto, that ensured equal rights to each member of the sejm. From then on, every new law, or law change, had to pass without opposition.

Earlier military triumph, economic prosperity, religious freedom, and professed equality among its people unravelled below the extreme privileges of the few. Personal agendas constipated the parliament. Neighbouring enemy states that befriended nobles—or found a means to bribe them—were able to manipulate the sejm without messy military confrontation.

_______________

Prosperity lived in Poland among extreme poverty. Religious tolerance during the “Golden Age” had led to an influx of those persecuted in other countries. Catholics, Jews, and Muslims found refuge in Poland, and Jewish communities thrived. Many Jews saw opportunities to work within the system, and created a level of prosperity between the nobility and the peasantry. An arrangement called arenda allowed Jews who allied themselves with land-owning lords, to tax and collect dues from the peasantry on the landowners’ behalf in any way they wished. This made those Jews as unpopular as the original landlords.

As land-owning magnates grew their power, the nobles lost theirs. Sejm members held onto their leverage at the expense of their commonwealth—and ultimately themselves. They refused to pass necessary law reforms and resisted supporting a regular army for fear it may be used against them. King Augustus III was said to have regularly summoned the sejm during his 30 years’ rule, but only one session passed legislation, which left Poland with no diplomacy, no treasury, and no defence.17

Poland’s neighbours took advantage of this dithering, and by the latter half of the 18th century, Russia and Prussia meddled freely in Polish-Lithuanian politics—aided in part by an alleged liaison between the last king of the commonwealth, Stanisław II August Poniatowski and the Russian empress Catherine II.

A faction of his own nobles, fearing for the future of their fragile society increasingly pecked at by Russia, gathered against their king and instigated a civil war they hoped would preserve the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

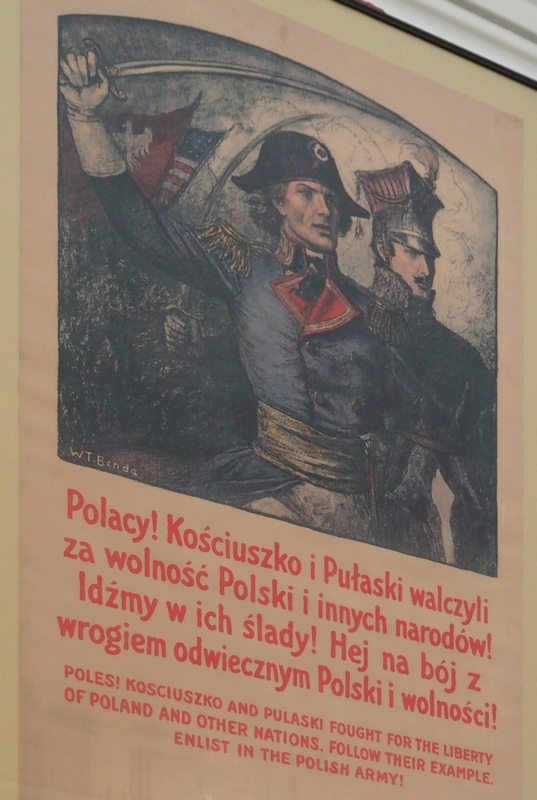

The Polish patriots, led by Kazimierz Pułaski, gathered at the fortress at Bar (now in the Ukraine) in 1768, but they were no longer the formidable military force of years past, and their demoralised ranks made it possible to sow rumours, which further weakened them.

Their defeat in 1772 led to Poland’s first partitioning by Russia in the east, Prussia in the west, and Austria in the southwest. Sejm members able to be bribed or influenced by Russia manipulated the liberum veto to ratify king Stanisław II August Poniatowski’s motion in favour of partitioning. Poland lost about a third of its land.

A 20-year national revival after 1772, which boosted economic prospects and promoted education, could not stop a second partition in 1793, when Poland ceded more land in the northwest to Prussia. The next year, Austrian troops joined those from Prussia and Russia and annihilated the Poles in a final battle at Maciejowice. But by then, not even the accomplished military leader and strategist Tadeusz Kościuszko could help his beloved country.

Despite being defeated by Poland’s partitioning neighbours, military leaders such as Kazimierz Pułaski and Tadeusz Kościuszko remained Polish heroes. Using posters such as this one, the new Polish army under General Józef Haller paraded their fame and reputations in urging Poles to enlist in 1918.18

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth teetered on until 1795 when it was partitioned a third and final time by its neighbour empires, and ceased to exist on geographical maps. Stanisław Poniatowski, the last king of Poland, was forced to abdicate, moved to Russia, and died in St Petersburg in 1798.

_______________

Jan Rajnold Forster was 43 when Prussia first seized Tczew, the town of his birth on the banks of the northern Vistula. In 1772, he was making an insecure living doing translations in London. His surname came from his Scottish great-grandfather, who left his homeland in 1642, the year the English Civil War started.

Some stories say that the first Forster in Poland left Scotland after he, like so many others, lost his property to Oliver Cromwell; others say that he was fleeing persecution for his faith; and others say that he was lured to the wars of central Europe by the thought of making a living as a mercenary. Whatever the reason, he joined the thousands who left Scotland to start a new life in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth still basking in its “Golden Age.”

This 1712 map of Poland shows the original names of familiar cities today.19

Jan Rajnold grew up hearing both Polish and German spoken at home. His father was once mayor of Tczew and the family could a fford to let him pursue his studies in theology, geology, and natural history. He married Justina Nicolai and settled in Mokry Dwór, where their seven children were born, their eldest son, Jan Jerzy Adam Forster, in 1754. Aged 11, Jan Jerzy accompanied his father in Russia, on a year-long contract to Catherine II. Jan Jerzy absorbed his father’s teachings in languages and the natural sciences, and joined him again when he moved to England to teach at the dissenting Warrington Academy.

Poland’s first partitioning happened to coincide with increasing British interest in the most southern reaches of the globe, and the tantalising possibility of discovering a great southern continent. The British Admiralty sponsored Captain James Cook and the hms resolution for a second “deep South probe.”

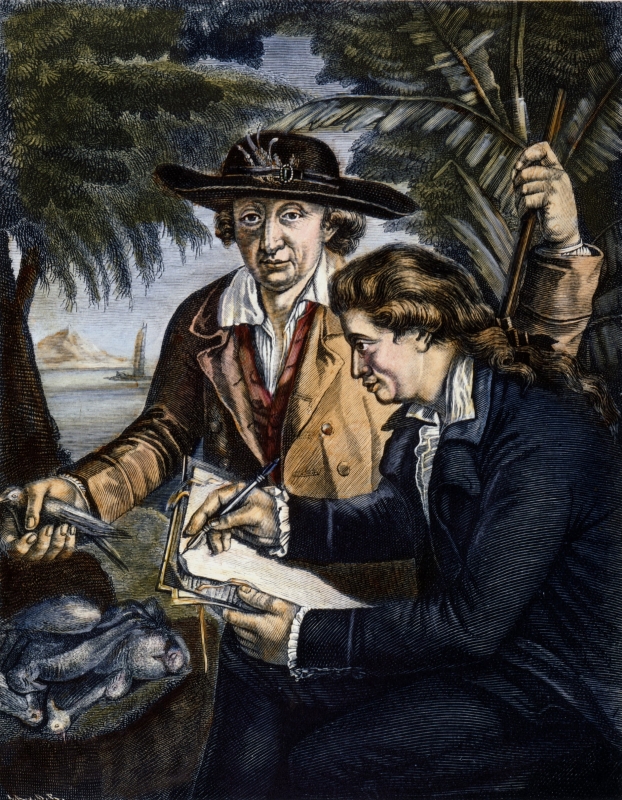

Joseph Banks, the naturalist and artist who accompanied Captain Cook on the hms endeavour from 1768 to 1771, withdrew shortly before the scheduled departure of the second expedition and Jan Rajnold Forster’s name emerged as a replacement.20 Forster did not have Banks’ large contingent, but his 18-year-old son proved his worth as an able assistant and talented illustrator. They became known as “two sons of the Commonwealth of Two Nations.”

In March 1773 in Dusky Sound, Fiordland, they were the first Poles to set foot on New Zealand soil.

This drawing of JR Forster appears in botanical discovery in new zealand: the visiting botanists.21 The publication does not mention the artist.

The description of Forster senior as “brilliant but cranky” is one of the more polite.22 Jan Rajnold was not known as the most tactful of people, and often disagreed with Cook. The Pole, for instance, disputed Cook’s concept that sighting sea ice meant proximity to land, and that only unsalted water could produce ice. The British Admiralty needed to agree with Cook’s hypothesis to gain funding for more voyages. When the expedition returned to England, the Admiralty forced Jan Rajnold to honour the narrow confines of his contract, squeezed him out of a joint publication with Cook, and refused to allow him to publish independently before the captain, who did not share the same urgency to produce a book as the cash-strapped father of seven.

The conflict resulted in Jan Rajnold’s facing the pauper’s prison, and disillusioned Jan Jerzy, who knew that the two narratives covered completely different aspects of the journey: His father listed and described the several hundred new species of fauna and flora they had discovered, while Captain Cook focused on navigation and mapping.

Jan Rajnold gave his resolution journals to his son, who—not bound by the same publication restrictions as his father—took over the writing of their joint observations.

Six weeks before Captain Cook’s account of the voyage appeared in print, the Forsters published Jan Jerzy’s two-volumed: a voyage round the world in his majesty’s sloop, resolution, commanded by capt. james cook, during the years 1772,3,4,5.23

In the preface of his book, Jan Jerzy set out his disappointment about the way his father had been treated. First, he acknowledged the talent and intellect on the resolution:

The greatest navigator of his time, two able astronomers, a man of science to study nature in all her recesses, and a painter to copy some of her most curious productions, were selected at the expence [sic] of the nation…

The British legislature did not send out and liberally support my father as a naturalist, who was merely to bring home a collection of butterflies and dried plants…

So far from prescribing rules for his conduct, they conceived that the man whom they had chosen, prompted by his natural love of science, would endeavour to derive the greatest possible advantages to learning from his voyage…

An agreement was drawn up on the 13th of April, 1776, between captain Cook and my father, in the presence, and with the signature of the earl of Sandwich, specifying the particular parts of the account which were to be prepared for the press by each of the parties separately… but after some time [my father] was convinced, that as the word “narrative” was omitted in the agreement, he had no right to compose a connected account of the voyage…

I must confess, it hurt me much, to see the chief intent of my father's mission defeated, and the public disappointed in their expectations of a philosophical recital of facts. However, as I had been appointed his assistant in the course of this expedition, I thought it incumbent upon me, at least to attempt to write such a narrative.24

Both books cost two guineas. Cook’s included more than 60 prints and sold well but Forster’s did not even cover publication costs. To help clear his debts, Jan Rajnold sold many of his son’s botanical drawings to Joseph Banks.

Jan Jerzy could have written his book in Polish, German, Latin, French, Russian, or English. In 1775 and 1776, the Forsters published a Latin edition describing 75 new genera and 94 new species.25

His father’s financial predicament put pressure on Jan Jerzy to support his father’s family as well as his own. A German version of the book came out in 1778. In 1784 the younger Forster moved to Wilno (now Vilnius in Lithuania) to take up a position as a professor at the Polish University. His last move was to Paris, where he died, aged 40, not living to see his country’s final partitioning in 1795.

His distant Scottish heritage meant that his surname was not automatically recognisable as Polish, and neither were versions of his Christian names, which included Georg, George, and Joannes Georgius Adamus. He may have spoken at least six languages, and lived outside partitioned Poland, but he never doubted his nationality.

In 1792, while living in Paris, he received a letter from Minister of Prussia, Ewald von Hertsberg, in which the minister instructed him to “behave like a good Prussian.” Jan Jerzy Adam Forster replied:

Urodziłem się na ziemi polskiej o milę od Gdańska; opuściłem tęż ziemię rodzinną w chwili, gdy przeszła pod panowanie pruskie, a więc nie jestem pruskim poddanym. (I was born in Polish territory, a mile from Gdańsk, and I had left my motherland when it passed under Prussian rule. Therefore, I am not a Prussian citizen.)26

He is said to have repeated this statement in several scientific and other publications. In his reply to Von Hertzberg, Jan Jerzy said, “Ubi bene, ibi patria,” translated from the Latin: “Where you feel good, there is your home.”

Jan Rajnold and Jan Jerzy Forster in Tahiti. This appears to be plate five of a series engraved after the resolution voyage, paid for by the British Admiralty, and jointly owned by captain Cook and the senior Forster. John Francis Rigard painted the image in 1780.

Jan Jerzy’s assertions to von Hertzberg highlights the complexity of Polish nationality, not made easier today with Polish diaspora accounting for between 10 and 20 million living in more than 90 countries. In the 2006 New Zealand census, nearly 2,000 people classified themselves as Polish,27 marginally more in the 2013 census. Both numbers are considerably smaller than the statistics gathered by the Polish Embassy in Wellington, which records at least 6,000 Poles of varying ancestries living in New Zealand.

The discrepancy may be because there is no specific category for Poland on the census forms and, unless one was born in Poland, there is no accurate count of those in New Zealand who have Polish heritage. With no mention that the form can capture up to five ethnic groups for each person, there is a natural tendency for Poles born outside Poland to classify themselves as “New Zealand European.”

Jan Jerzy considered himself a Pole but, after Prussia absorbed the part of Poland where he was born, he could have been classified by officials as any combination of Polish, Prussian, or German.

Outside Poland, his Scottish-sounding surname would have steered people who did not know him away from his Polish ancestry. The various languages that father and son spoke would also have provided them with an ease in any number of countries. Their ability to travel and gain employment in other countries was a luxury not available to Poles who lived rurally and were indentured to nobles and landlords.

Poles from the farming communities of the same Prussian-occupied Poland as the Forsters did not have the same language capabilities or ease of travel when they decided to leave their country 100 years after Poland’s first partitioning in 1772.

After 1795, the Prussian partitioners of northwest Poland gradually added pressure on the population to relinquish their Polish roots. The new authority started to germanise the spellings of geographical entities like towns and rivers but by about 1848, it was unlawful for clergy to baptise or register a child with a non-German Christian name. Later, it became impossible to officially register original Polish surnames for marriages or deaths.

Until the abolition of Polish serfdom after 1863, nobles received protection from name changes. Some serfs manipulated this nicety and tried to keep their Polish surnames by adding the suffix “ski” to signify their attachment to the house of a noble. Subtleties like that did not work once Otto von Bismarck rose to power and set about creating one vast German Empire that would incorporate all the various states that the Germans already controlled. After the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War, it became illegal in Prussian-partitioned Poland to speak, write, read, or keep anything written in Polish. Polish schools were banned. Polish priests disappeared.28

Kaszubian and Kociewian Poles who cherished their ancient dialect were among those who refused to send their children to Prussian schools. This stubborn response created an illiteracy that the Poles may have coped with were it not for the increasing discrimination against their Catholic faith and the theft of their lands, as happened to 17 Polish families from Kokoschken.

The modern growing fields of northwest Poland.

Barely able to grow enough to feed their families on their own small pieces of land, they accepted employment as labourers at a neighbouring German’s farm. When the Franco-Prussian War started, the farmer suggested he had the means to arrange it with authorities that, if the Polish farmers gave him the deeds to their land to “hold,” they could spend the war growing food for the Prussian army instead of facing conscription. This suited the Poles, who did not relish fighting on the side of their occupiers.

The war ended a year later. The Poles requested the return of their deeds. The farmer refused—on the basis that he had given them the chance to save their lives. The villagers had no choice but to continue toiling for an employer without scruples in a land where they had no rights.

A Pole in Kokoschken who could read saw a pamphlet extolling the virtues of a new country overseas that offered employment and a deferred method of payment for their passage. The Polish villagers embraced the idea and investigated. The farmer found out and evicted them, and cemented their resolve to leave their homeland.29

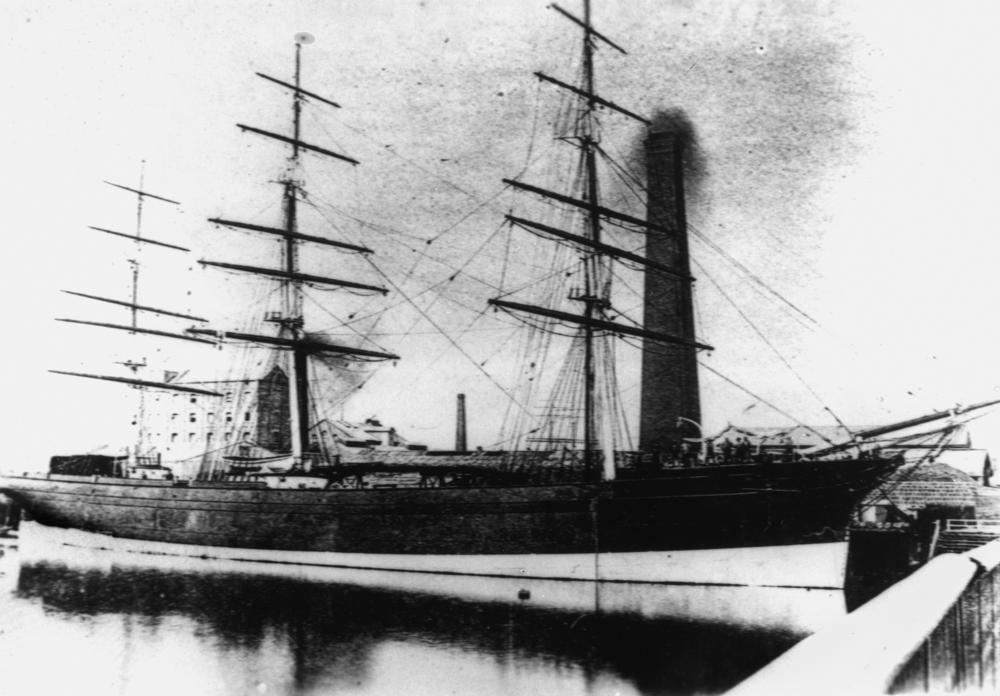

They arrived in Wellington aboard the fritz reuter to find that the country on which they had based their futures had terminated its assisted immigration scheme from continental Europe. The evening post on 5 August 1876:30

The arrival of the Fritz Reuter with 420 German [sic] adult immigrants caused a complication which at one time threatened to be rather awkward… the immigrants were despatched by the Continental agents after instructions had been given to the Agent-General… not to send out any more shipments of foreigners… On their arrival here being notified to the General Government yesterday, the latter declined to receive or recognise them, declaring their shipment wholly unauthorised.

German Consul FA Krull applied to the government to take charge of the immigrants and broke the impasse. The fritz reuter passengers disembarked on Tuesday, 8 August 1876.31

The fritz reuter in port in Hamburg.

_______________

Single men, sailors, or adventurers of all nationalities, who arrived in New Zealand in the 100 years after Cook’s voyages, decided for themselves how much of their backgrounds to declare, and what to suppress or reinvent.

Ships operating under New Zealand’s Immigration and Public Works Act of 1871 documented all immigrants. Polish immigrant groups started arriving in 1872 and were usually listed as being German or Prussian. Those without the ability to write, or without the help of someone who could, had to rely on their spoken language to explain who they were.

Polish names germanised under Prussian rule underwent anglicised changes, understandable in a situation where documenting officials were not used to the Polish language’s proliferation of combined consonants, or its diacritic marks.

The many mistakes took away the most basic clues to their Polish identity—the richness of their country’s alphabet. For example: “Bielawski” became “Bolosky,” “Szymański” became “Schimanski,” “Zdonek” became “Dunick,” “Piekarski” became “Perkasky” or “Pieharski.” Some officials tried harder than others, but some were blatantly bigoted: “Czablewski” became “Shoplifski” and “Czepanski” became “Shamelifski.”32

Theoretically, the earliest Polish settlers to New Zealand could not have been Poles because Poland did not exist at that time. Nearly 100 years after the last partition of Poland, none of them had been born on free Polish soil. What made them Polish was more than ancestry. It was their spirit.

Some of those first Poles may not have wanted to protest too much about their name changes. When starting a new life in a new country, it is always easier to fit in when one is not too different.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated August 2024

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Greater Poland Chronicle, 13th – 14th centuries.

From a display at the Museum of Independence, 62 Aleja Solidarności, Warsaw. - 2 - Długosz, Jan, Annals, or Chronicles of the Famous Kingdom of Poland, 15th c.

Ibid, the Museum of Independence. - 3 - Initial source: from www.kasprzky.demon.co.uk.

- 4 - I have used Piast as Siemowit’s surname. Polish history books tend to use only the Christian names, and

indirectly link them to the “Piast dynasty.”

https://www.edukator.pl/resources/page/wladcy-legendarni/4999 - 5 - Eljasz-Radzikowski, Walery (1841-1905), Królowie Polscy w Obrazach i Pieśniach, 1893, Poznań,

Karol Kozłowski,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Walery_Eljasz-Radzikowski,_Ziemowit.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Copyright_tags/Country-specific_tags#United_States_of_America - 6 - Deitrich, or Theodoric, of Haldensleben, of Saxon Nordmark.

- 7 - This image from:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mieszko_I_of_Poland.jpeg

Ibid, US Public domain tag. - 8 - The exact birthdate of the word Poland eludes me, but I decided that this was as good a place as any to start using it.

- 9 - Thanks to Wikimedia Commons, used under the Creative Commons licence.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DagomeVatican-1Copy.jpg

Ibid, US Public domain tag. - 10 - Dr. hab Marek Kazimierz Barański, Prof. dr hab. Teresa Chynczewska-Hennel & Dr. hab. Andrzej Szwarc, The History of Polish Diplomacy, p 14, First edition 2010, published by Bosz, Lesko.

- 11- https://www.edukator.pl/resources/page/kazimierz-i-odnowiciel/2066

- 12- Ibid, Barański, Chynczewska-Hennel & Szwarc, p 25.

- 13- Photograph of the sword taken at the Museum of Independence in Warsaw.

For more information on the sword, see https://polisharms.com/szczerbiec/ - 14- The Marcello Bacciarelli image was sourced through the Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jadwiga_of_Poland.

Ibid, US Public domain tag. - 15- According to the Warsaw Museum of Independence, where it was displayed in 2016, this version came from the Sejm Library, Museum Department.

- 16- A map named POLAND, CORRECTED from the Observations communicated to the ROYAL SOCIETY at LONDON and the ROYAL ACADEMY at PARIS that shows the extent of the commonwealth circa 1712, is held at the Sir George Grey Special Collections at the Auckland City Library.

- 17- Davies, Norman, Europe, A History, p 659. Published by Pimlico, 1997, London.

- 18- Photograph of the poster taken at the Museum of Independence in Warsaw.

- 19- Digitised copy of map bought from the Auckland Libraries Sir George Grey Collection.

- 20- Thomas, Nicholas, Discoveries, The Voyages of Captain Cook, p 150, Published by Penguin Books,

2003.

Note: the author spells Jan Rajnold Forster’s name “Johann Reinhold Forster” and his son, Jan Jerzy Adam “George.” - 21- Oliver, WRB, School Publications Branch 1950, part of the New Zealand Texts Collection,

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-OliVisi-t1-body-d1-d1-d3.html#OliVisi-fig-OliVisi017a - 22- Ibid, Nicholas, p xviii.

- 23- Digital Archives and Pacific Cultures

http://pacific.obdurodon.org/ForsterGeorgComplete.html - 24- Forster, Georg, statement 1 March 1777, London, taken from the preface of his book, A Voyage Round the World in His Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the Years 1772, 3, 4, 5.

- 25- New Zealand Electronic Text Collection through the Victoria University of Wellington,

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-SamEarl-t1-body1-d2-d6.html - 26- Ibid, Wójcik, Z.

- 27- New Zealand Department of Statistics.

- 28- Initial source: Ray Watembach, president Polish Genealogical Society of New Zealand.

- 29- From The Fabisz/Fabich/Fabish Story, pp 2, 3 & 5, used with permission of Rod Fabish.

- 30- Evening Post, 5 August 1876, p 2, column 4, Papers Past, through the National

Library of New Zealand, Creative Commons licence New Zealand BY-NC-SA,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP18760805.2.6? - 31- For more on the Fritz Reuter story, see:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/fritz-reuter/ - 32- Pobóg-Jaworowski, JW, History of Polish Settlers in New Zealand, 1988, p 20.