Jackson’s Bay, 1874-1879: Resolutely Untamed

It takes people who are brave, strong, and visionary to break in new ground. Those able to choose where to break that ground make sacrifices because they believe in their choices. Others have circumstances thrust on them.

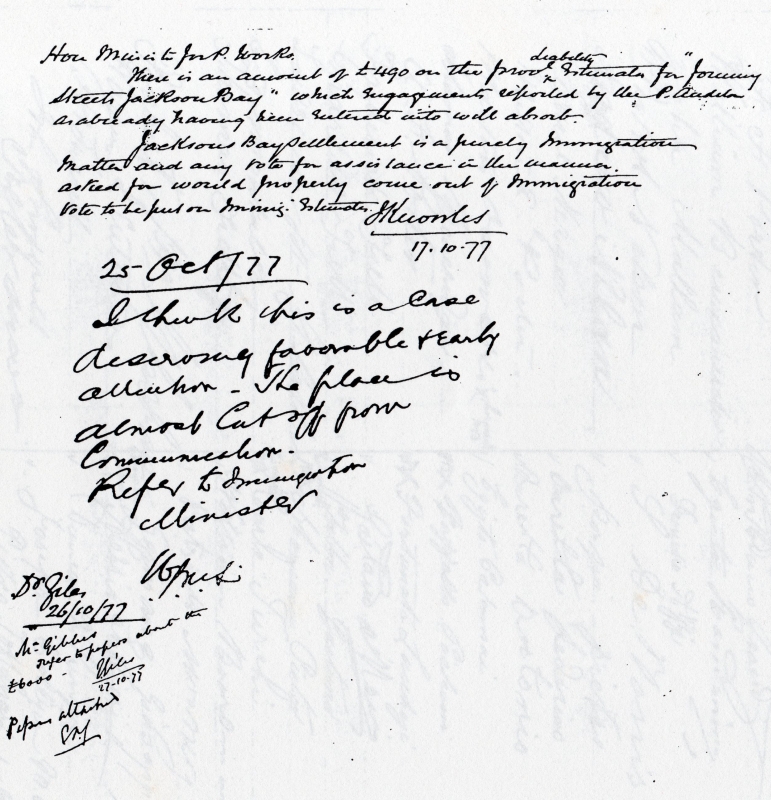

If it had not been for an 1879 commission of inquiry into the Jackson’s Bay Special Settlement on the West Coast, we would have known little of the challenges and adversities of its first settlers. Official records would have remained as just that—officially formal and detached from the reality of life that many people endured in what is still one of the most remote places in New Zealand.

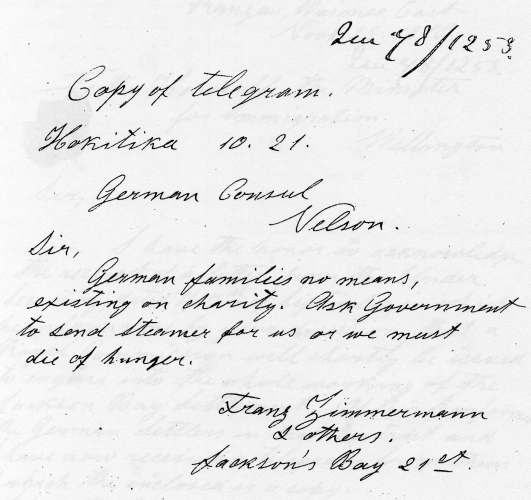

The Polish settler families who became part of the fractured Jackson’s Bay community between 1875 and 1879 would have melted away. Official correspondence about their existence in the settlement would have been left at comments on two tragic deaths, and the group among those blamed for the demise of the settlement.

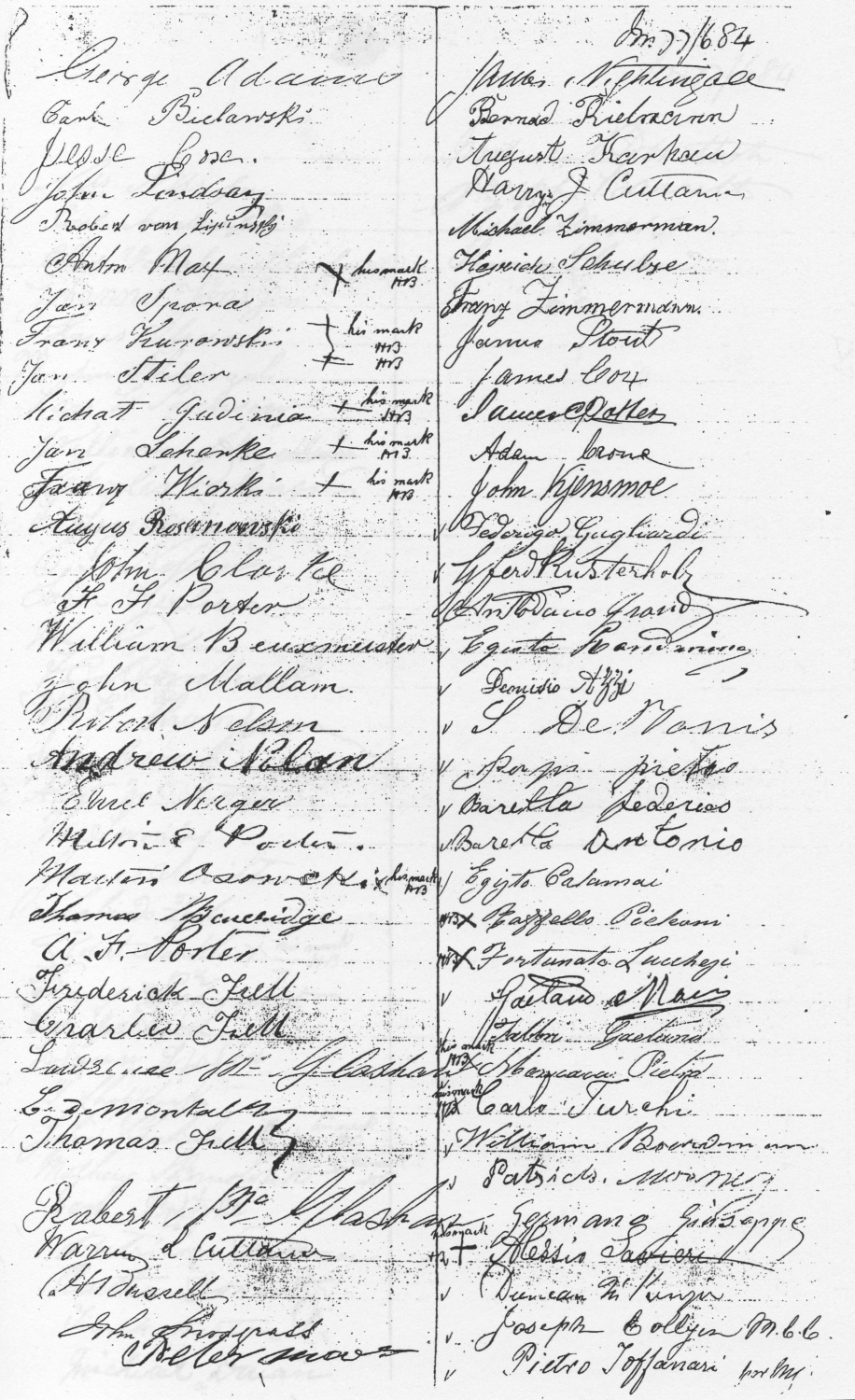

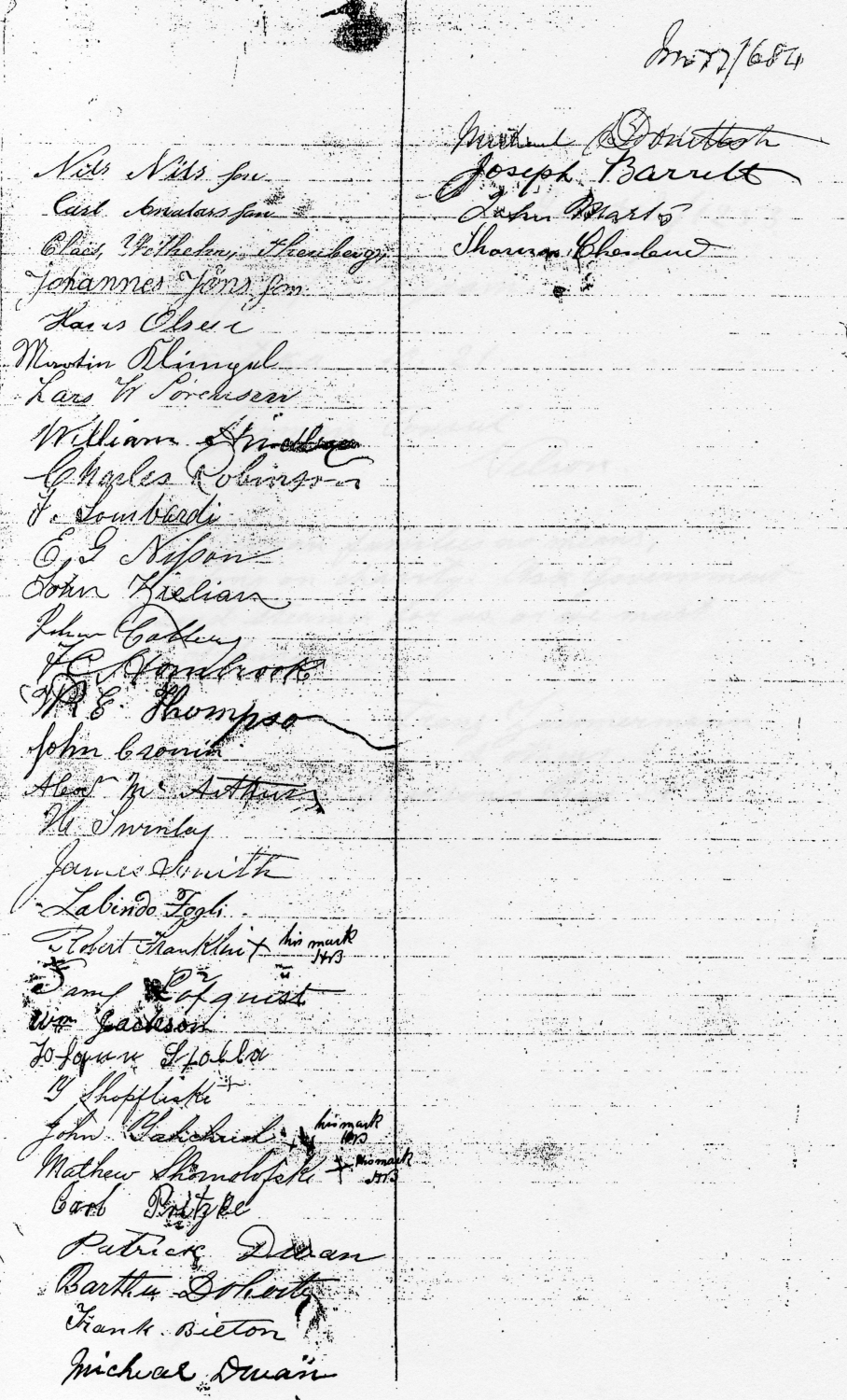

This story has been possible because the English-speaking settlers who felt they had been exploited and unfairly treated, had the courage to protest. They wrote to newspaper editors and drew the attention of Hokitika’s House of Representatives member for Hokitika Edmund Barff. They petitioned the colonial government.

In researching this saga, I made extensive use of the Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives and put slightly less weight on anonymous individual letters to editors. I noted that those with grievances who spoke at the inquiry, held at the Hokitika courthouse, had to have the means to attend. For those who left Jackson’s Bay destitute, and who lived far from Hokitika, travelling there would have been beyond them—even if they had known such an inquiry was happening.

Today Jackson Bay has lost its possessive.

—Barbara Scrivens

Jackson Bay in 2010.

THE END OF THE ROAD

by Barbara Scrivens

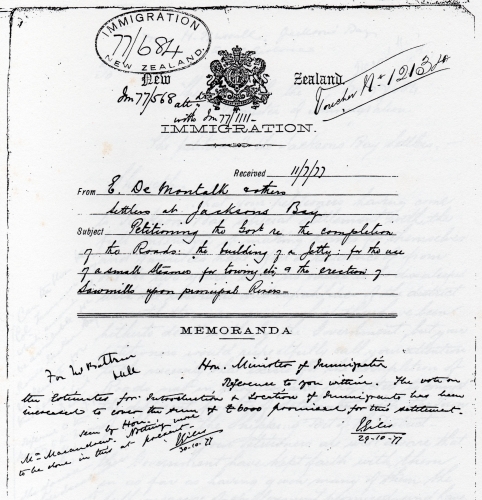

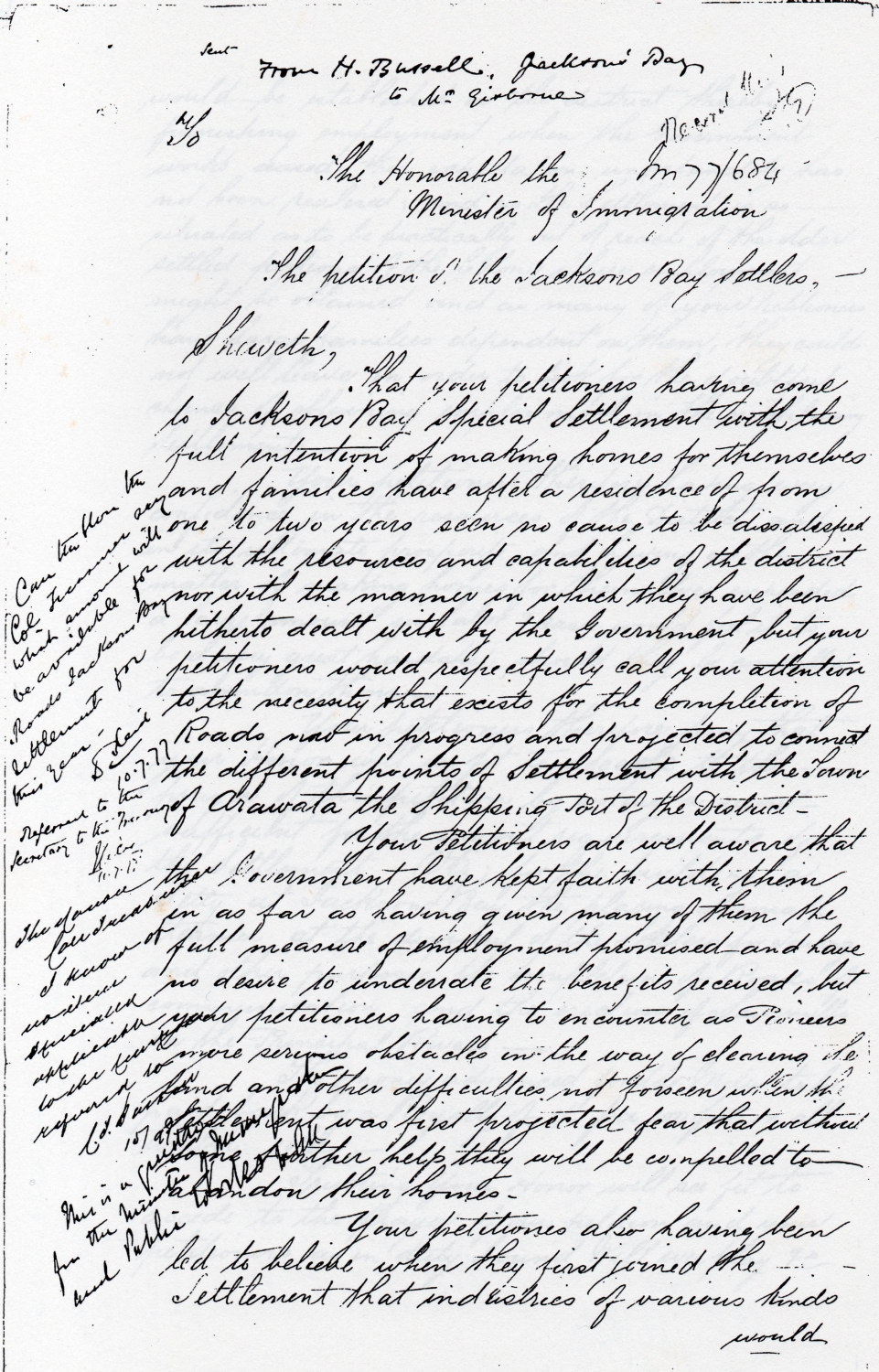

Resolution of the House of Representatives, 20th August 1878.

That the Government be requested to take immediate steps to cause a public and impartial

inquiry to be held into the working of the Jackson’s Bay Special Settlement, and that any persons who may feel themselves

aggrieved may have ample opportunities afforded them of giving evidence on oath before any tribunal which may be

appointed.

(—Mr. Barff)

European settlers first waded through the chilly summer waves of Jackson’s Bay on 19 January 1875.

We know the date. We know the names of the 23 men—many with families—who stepped onto its rocky shore. We know they were promised a bright future. We do not know whether that particular day contributed to the more than 300 centimetres of rain that fell on 186 days that year.

Originally from Scotland, England, Scandinavia, Canada and Germany, those first settlers were chosen for their experience as colonists in New Zealand, and were expected to pass on their knowledge to future immigrants.

During the next four years, at least another 122 single and family men joined them, including 26 Polish men with wives and children, two single men related to the Polish families, and one single Polish woman—Marianna Bielawska, who was Carl Bielawski’s sister, but who travelled to New Zealand earlier than her brother and arrived in Jackson’s Bay with others off the Lammershagen in August 1875.1

Those who arrived in 1878 still trudged through the same water, but had an increased probability of being drenched from above as well as by the sea. Rain fell on 212 days that year, which pushed the annual precipitation to nearly 350 centimetres.

By the time the commission of inquiry sat in March and April 1879, 95 surnames had been erased from the list of inhabitants. Of the 174 men on that list, the word “left” appeared against 113, and seven were dead.2

Five men—two from out-of-town—and a 10-year-old boy drowned in one incident off Big Bay in 1878. Rosalia Wicki’s death a year earlier was profitable for a West Coast Times correspondent. At least six newspapers repeated the “horrible accident” that befell her:

…the wife of one of the Polish settlers at Smoothwater, named Wietzki [sic]. A coroner’s inquest, presided over by D. Macfarlane, Esq, R.M, elicited the following:—On the 30th June, Wietzki [sic] was cutting down a tree which he had already been admonished two or three times to remove, because it was close to the house, when suddenly the tree, which was rotten in the middle, fell down upon the roof of the house, crushing to death, in its sudden and unexpected fall, the poor woman who was at the time engaged in household duty, and had her infant child in her arms. The latter, however, was providentially saved from the horrid death of her mother. The jury returned a verdict of “Accidental death.”3

The “infant” was two-and-a-half year old Franciszek (Frank) Teodor Wicki. In a letter dated 27 July 1877, resident agent for Jackson’s Bay Duncan Macfarlane told Westland superintendent Edward Patten: “I have the honor [sic] to report that on 29th June a settler’s wife at Smoothwater met with her death through the falling of a tree on his house.” Macfarlane’s official explanation omits to say that the tree was rotten, that he ordered Franz Wicki to cut it down, or that it was so close to the house:

The circumstances were as follows:—The husband of the deceased was cutting down a tree in the neighbourhood of his house, and he told his wife to keep outside until such time the tree was down, as it might fall on the house. She expressed great fear about the tree, but, for some unaccountable reason, just before the tree was cut through, she went inside, and before she could get out she was caught by the falling tree and was killed on the spot…4

Macfarlane: “The accident threw quite a gloom on the settlement.”

If Macfarlane did find out Rosalia’s or Franz’s names during the coroner’s inquest he presided over, he did not mention them in his report. Of the 16 recorded burials and deaths transcribed in the Arawata Pioneer Cemetery records in 1980, Rosalia’s entry is: “UNKNOWN Polish settler’s wife, killed by falling tree, 29 June 1877, Polish Settlement, Jackson’s Bay.”

The Wicki family of five had arrived in Jackson’s Bay in July 1876. Franz left with his children—Julianna (8), Bernard (5) and Franz junior—six months after the accident.

_______________

The first group of settlers arrived in Jackson’s Bay with framing for 20 government houses. Offloading in the choppy surf would have been more problematic than deciding where to erect them—the area adjacent to the beach provided the only flat ground. The cottages became rent-free accommodation for them while they cleared their own land and built their own houses.

Colonial surveyors had praised the area for its potential. They maintained that the mountains surrounding Jackson’s Bay held gold, silver, quartz, and coal; that the dense timber waited to be cut and sold to a ready market; that the harbour teemed with fish.

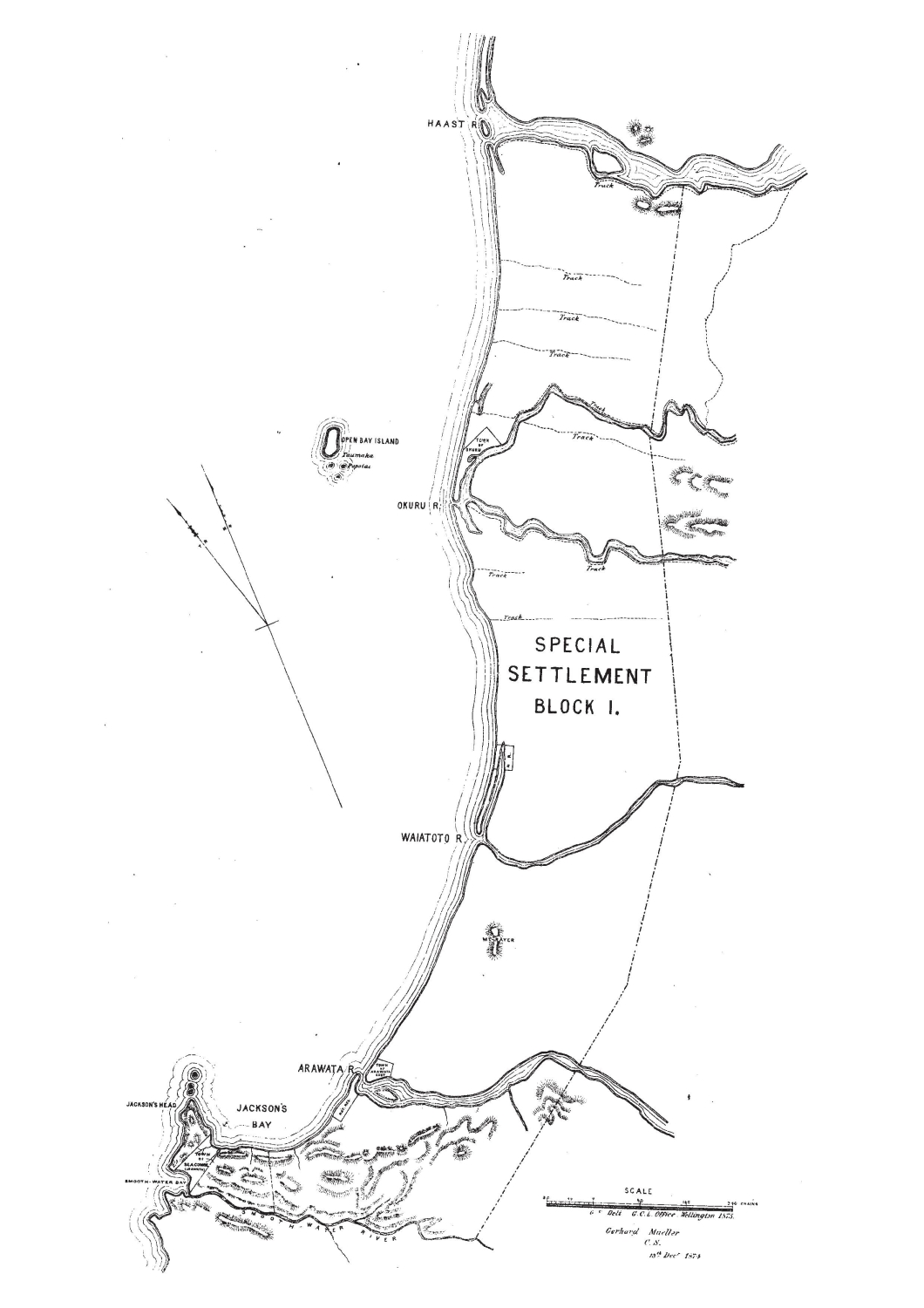

While written reports by Westland’s chief surveyor and provincial engineer, Gerhard Mueller, brimmed with positivity, maps that bear his name clearly show its geographical challenges: five rivers south of the substantial Haast cut up the land. The Okuru (north) and Turnbull rivers met at the Okuru estuary, the Waiatoto and the Arawata (now Arawhata) ran through the flatter land, and the narrowest Smoothwater River—where the Wickis lived on 50-acre block number 111—was south of Jackson’s Bay and butted against a range of hills, all shown in the map below.5

Gerhard Mueller’s map dated 13 December 1874.

The Arawhata River, north of Jackson Bay, in 2010.

Transport overland was never going to be a viable option. Jackson’s Bay itself may have provided the best natural harbour on Westland’s coast but the hills and the rivers hemmed it in, and all provisions had to be delivered by steamer.

_______________

The men and women who came and left between 1875 and 1879 bore the brunt of the blame for the settlement’s inevitable failure. They arrived with hope, fuelled by the promises of the government’s advertising pamphlet. They left, often destitute, their efforts thwarted more by an unpredictable and unreliable bureaucracy than anything the terrain or climate threw at them.

New Zealand’s colonial government allocated £20,000 for Jackson’s Bay, a site chosen by a Westland Select Committee. Decision makers either did not consider negative aspects of the area, or glossed over them. Government ministers and their advisers in Wellington seemed unaware of the brutal and unrelenting climate, the density of the forested interior, and the obstacles facing anyone building anything on such a craggy terrain.

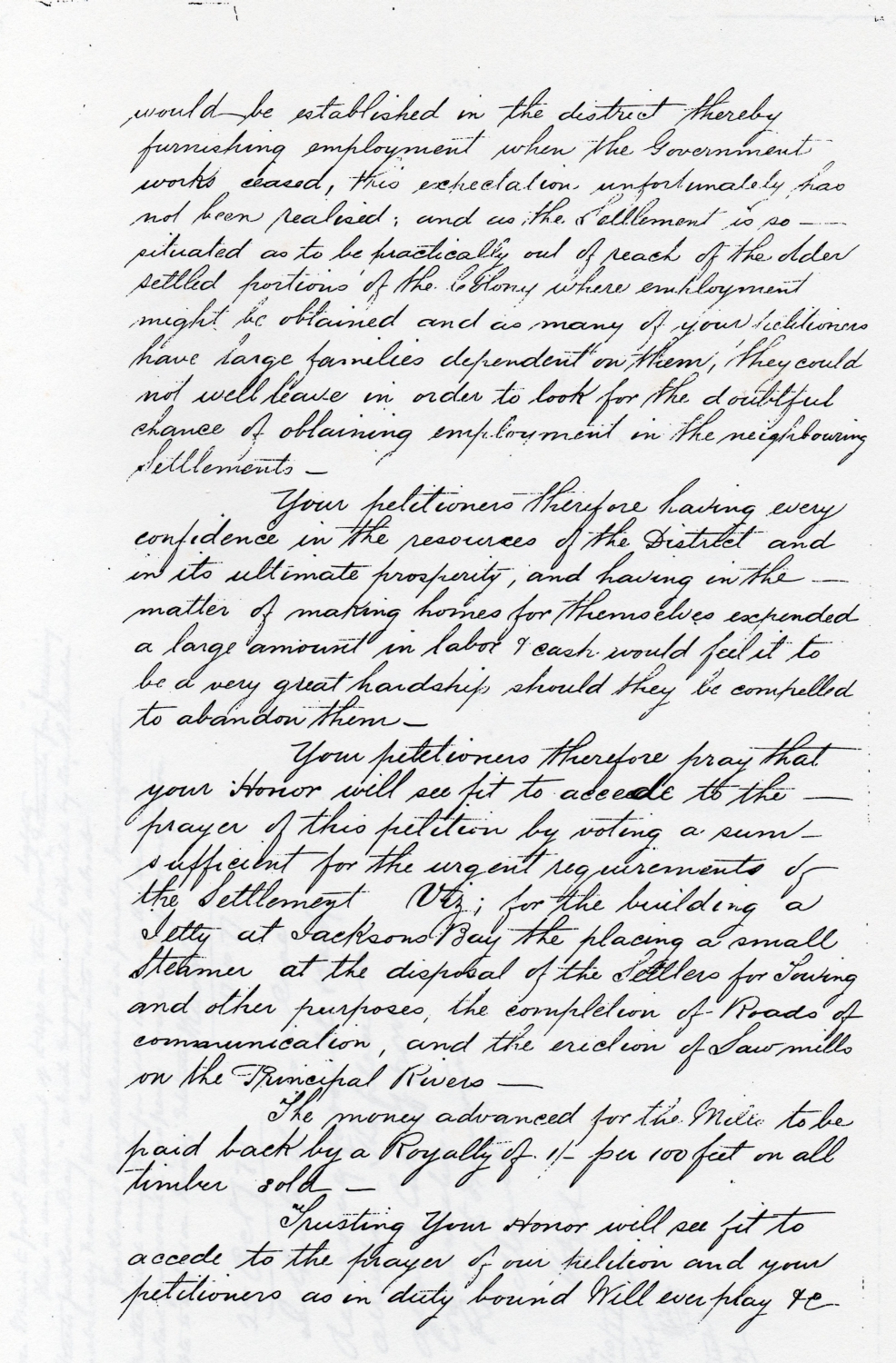

The government promised the prospective settlers employment, land under “extremely reasonable conditions” and provisions “at cost”. Sections sold to settlers were to help repay the government’s advance to the settlement.6

At first, the inducements created more applicants than positions. Westland’s “first and only” superintendent, James Bonar, wrote to immigration minister Harry Atkinson telling him of the “great care” he had taken in selecting suitable candidates.7

The Grey River Argus printed out the extensive conditions in its 21 January 1875 issue, two days after the first settlers arrived. (See the full conditions accompanying this story.)

The last point, number 16:

16. The money to arise from the sale and disposal of lands within the said settlement shall be applied for the following purposes:—

- – In defraying the expenses incident to the formation and laying out of such settlement:

- – In making and constructing roads and any other necessary public works within such settlement:

- – In establishing, endowing, and maintaining public schools and any other necessary institutions within such settlement:

- – In maintaining communication, either by sea or land, with such settlement:

- – In constructing harbour works, wharves, &c, for the settlement.

By the time they reached point 16, earlier statements may have already seduced potential settlers: the settlers were to be “landed free of cost” and allowed to live “free of rent for a period sufficient to enable them to get dwellings erected on their own sections.” Seven years’ rental payments on those sections entitled them to permanent occupation. Another statement assured employment at “half time during the first two years of settlement” for public works such as the construction of a “main road” from the Jackson’s Bay township to the Haast River.

Mueller told the commission of inquiry on 5 April 1879: “It was thought likely at first that discoveries of minerals would give the district a start, and that those settlers who had cleared their ten-acre sections would be able to sell them, and go on to their [50-acre] rural sections. But a mistake was made at first in sending the first settlers before the surveys had sufficiently progressed.”8

According to the General Conditions, the quarter-acre town sections were to be sold for cash at auction. Any adult male settler was entitled to “take up” one suburban section of 10 acres and one rural block of 50 acres. Suburban sections cost six shillings an acre per year, and rural blocks three shillings an acre per year.

At first, Mueller suggested that each settler receive a town, a suburban, and a rural section, but the General Conditions do not mention settlers buying land in the town, and not one settler was recorded as living there—apart from during the initial settling-in rent-free period.

The free government cottages occupied the flattest quarter-acre sections. Within four months, the settlers had built shops for a blacksmith and a carpenter, and a toolhouse on one side of the flat beachfront, and on the other side a government store, and surveyor and resident agent’s offices.9

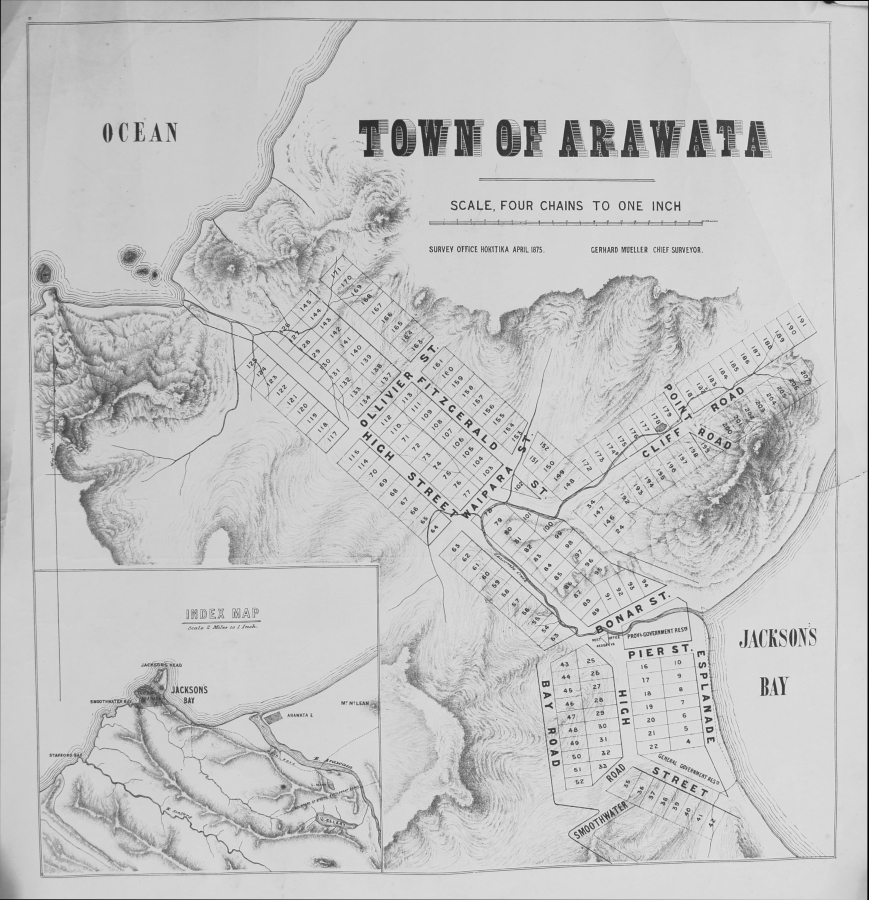

Mueller’s ambitious map of the proposed Arawata township, dated April 1875.10

Mueller drew 207 “town” sections, averaging 900 square metres, between Jackson’s and Smoothwater Bays. His map shows that his geometrical divisions of the town sections bear little connection with the terrain. He conceded the “hilly nature” of the township made it “peculiar” and that the roads for these sections would have to accommodate the contours11 but placed roads and sections over significant streams running towards both shores.

Who would have bought the steeper town sections? Or those on—or between—the bends of such streams? Living in the town might have appealed to employees of timber and fishing industries, but those industries did not materialise. Diggers tended to live in tents close to the sources of their claims, and used hotels when they came into a town.

The town had at least one permanent family—the Macfarlanes. They lived on the provincial government reserve, north of Pier Street in the map above, and shown in more detail below.

The Macfarlane house was on the inner side of the reserve on Pier Street, on section 15, and the store was built on section 11, facing the beach, its number on the map partly obscured by the ‘m’ in the word “GOVERNMENT”.12

At a £3 yearly rental for a suburban 10-acre section, and £7 10 shillings for a rural block, it is not clear how the writers of the General Conditions envisaged the settlement ever being able to fund its own infrastructure—never mind pay back loans—without many more settlers.

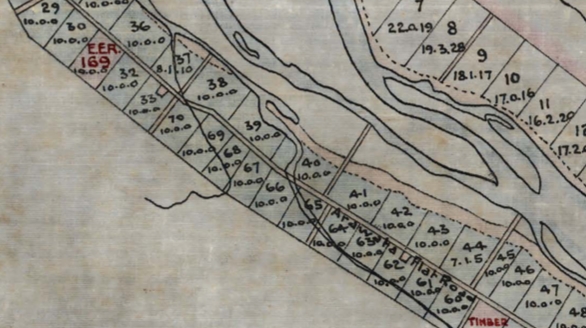

Surveyors’ maps of the rest of the settlement show a similar disconnect with the terrain, especially the vicinity and possible impact of rivers. A map signed on 23 October 1880 superimposed sections over tributaries of the Arawata, Waiatoto, and Smoothwater rivers.

The year after the inquiry, the General Crown Lands Office in Wellington appointed former resident agent Duncan Macfarlane Crown Lands Officer for Jackson’s Bay. In November 1880, Macfarlane wrote to then Commissioner of Crown Lands in Hokitika, Joseph Giles, to advise him of his appointment and that his salary would be sent through the Hokitika office. (Giles had been controversially appointed Under-Secretary of Crown Lands, Goldfields, and Immigration in 1877, and had been one of the three commissioners appointed to the Jackson’s Bay inquiry.) In his letter, Macfarlane referred to the settlement’s Land Return, which he had apparently been asked for, to identify the settlers who had fulfilled their contractual conditions and who were therefore due to receive the promised Crown grants. Macfarlane said that Giles would have “no difficulty in comprehending the positions of every section in the settlement” if he referred to the maps in the Hokitika office.13

The Land Return was divided into the eight blocks outside the main township and listed the positions of the sections, their size, the original occupant, the current occupant, the date of the original occupation, the date of abandonment, the rent paid, and the improvements made.

Arawata South was the only area that provided 10-acre sections—47 of 70 occupied in March 1875—and had a school reserve. The first seven Polish families recorded as settling there all arrived in Wellington off the Lammershagen on 11 July 1875, and all took possession of their sections five weeks later: Czaplewski (the return spelt the name Shaplifski); Czepanski (the return spelt the name Shamlifski); Gdaniec (the return spelt the name Donitz); Jakusz (the return spelt the name Jacques); Pricki (the return spelt the name Pritzki); Różanowski (the return spelt the name Rosanofski); and Tobian, whose son Rudolf also qualified for a section and took the one next door to his parents’ one.

According to the map, the five sections recorded as “unoccupied” all promised issues with the Arawata River’s tributaries, which ran through or on either side of at least 17 of the sections farthest inland.

Most of Arawata North’s 29 sections, which ranged from 15 to 50 acres, remained unoccupied in 1880. Four people took on two smaller sections each in November 1877, and one person took on the only 50 beachside acres in December 1876, which was next to two ferry reserves.

In Waitoto, 58 of the 77 sections remained unoccupied in 1880. The earliest occupation was 29 February 1876.

Out of 20, Okuru River South had four sections occupied, the earliest being taken up in June 1876. No one was interested in any of Okuru River North’s 32 rural sections. Settlers occupied 12 out of 21 sections in Turnbull River South, which also provided an education reserve, a school reserve, a general reserve, and a timber reserve. North of the Turnbull River, 19 of the 34 available sections were occupied from September 1876.

Smoothwater first opened on 13 March 1876 and had 42 predominantly 50-acre sections. According to the list, 24 of these had never been occupied, most of the others had been occupied for a time by Polish families, and all were abandoned by 1880. It is not clear what happened in the intervening seven months to the eight families off the Lammershagen who did not receive Arawata sections, but two did get Smoothwater sections: the Gudyniak family (Boddinach on the return), and Joseph Max (Maskrunski on the return).

Omitted completely from the return were the families Gorowski, Kreft, Max (two of Joseph Max’s uncles) and Stoba, plus their fellow-passenger, Frederich Brzeszki, aged 24, who arrived on 28 May 1875, and left three months later. They were most likely also steered towards Smoothwater, and were joined at Smoothwater by the recorded Ofsoski and Belecki families, who arrived at Wellington Harbour in January 1876 off the Shakespeare. The list omits Shakespeare passengers Franz and Anna Czuglewski (spelt Zylifski on other Jackson’s Bay returns).

The next nine Polish families arrived in Jackson’s Bay in July 1876 off the Terpsichore. The Bielawski, Karków, Spora, Sztela, Wicki, and two Zimmerman families apparently officially occupied their Smoothwater sections just two days after arriving at the settlement. One presumes that the entry for Franz Lehrke occupying his section on 13 March 1876 is an error, as he and his family were then still aboard the Terpsichore. The list omits the Klempel family, also off the Terpsichore.

The last two Polish families to settle in Smoothwater arrived via the Fritz Reuter, which sailed into Wellington Harbour in August 1876. Records show that Franciszek Kurowski took up his 50 acres at Smoothwater on 7 November 1876, and that his neighbour was Robert Lipinski, whose entry is again dubious, because the Fritz Reuter was not in New Zealand at the time he is said to have taken up his section.

_______________

When selling the idea in 1874, Mueller enthused about the area’s untapped value to the new colony.

The wild environment loomed large in Jackson’s Bay then, and still does. The heavily timbered hills and gullies plummeting towards rocky shores and narrow beaches continue to reflect the sometimes unrelenting rain.

Weather observations did not seem to feature in the chief surveyor’s December 1874 report yet he later placed the “exceptionally bad seasons” high on his catalogue of the settlement’s impediments.

When selling the idea in 1874, Mueller enthused about the area’s untapped value to the new colony. He declared that it contained “the very best description of agricultural land.”

He proclaimed the creeks would “prove of the utmost advantage to the settlers.” He brushed aside the same creeks’ steep banks of three to six metres, saying they would provide “natural main drains” for the entire block and that the “settlers’ work of drainage [would] extend to the cutting of small ditches only.” He did admit the area between the rivers north of Jackson’s Bay held a large proportion of “very swampy land” but asserted that settlers with “experience” could easily drain it, and be rewarded with a “great depth” of good-quality soil.14

Mueller’s opinion that a “very large extent of superior land… is ready for the plough as soon as cleared” summarises his tenuous linking of the area’s apparent potential and its major drawback: any arable land lay beneath bush that needed clearing. Mueller, like other officials, underestimated the difficulty of the process.

Superintendent Bonar surveyed the then-proposed settlement on 22 November 1874 with a group including Mueller and another surveyor, John Browning. They imagined a flourishing timber industry, supported by the “practically… unlimited demand” in New Zealand and its neighbouring Australian colony. The prospect excited Bonar to such an extent that he stressed in a letter to immigration minister Atkinson that “no time should be lost” in procuring a tramway with light rail for the project. He predicted sawmills employing many immigrants.15

The Polish families who settled in Smoothwater discovered too late that the benign-looking river with an amiable name had a tendency towards regular and destructive flooding.

In the same letter, Bonar enclosed Mueller’s glowing report, and that of the chief harbourmaster for Westland, Thomas Turnbull. The difficulty in landing supplies presented the largest obstacle for settlers in Jackson’s Bay, said Mueller. He recommended building a jetty running into the deep water. Turnbull said that the anchorages at Jackson’s Bay were “perfectly safe” for shipping.16

The surveyor Browning was “favourably impressed” with the Smoothwater area, and what he overestimated as 6,000 acres of viable land—it was little more than 1,000. The Polish families who settled there discovered too late that the benign-looking river with an amiable name had a tendency towards regular and destructive flooding.17

Mueller expanded on explorer and geologist Dr James Hector’s writings, Geological Survey of New Zealand During 1866 and 1867, in which Hector associated gold with the grey quartz and black iron sands along the beaches near Jackson’s Bay.

Mueller said that gold had been found “on every beach and in almost every water course” in the district and he was “absolutely certain” that the discovery of gold would “at once attract a large population” to the district. Heavier gold, he said, “has become a fact.” His message:

There is moreover the work of ‘beach combing,’ which has been successfully carried on… Whenever black gold-bearing sand is covering the beaches, the settler may leave off cultivating his ground for a few days and take to beach combing—one of the easiest and withal most remunerative descriptions of gold working, and, so earn a few pounds in a very short time.18

In the end, backtracking on the most basic of necessities—the jetty—became the insurmountable hurdle that helped Nature win the 1875–1879 battle at Jackson’s Bay. Without that jetty—estimated to cost £1,500—industry could not develop, and without that industry any anticipated private employment vanished.

_______________

If the surveyors had spent more time in the area’s forests and rain, in differing seasons, they may have recommended slower-paced development. They may not have underestimated so severely the harsh terrain, the climate, or even the never-ending supply of sandflies, always ready to feast on new skin. Captain James Cook mentioned the annoying insects in his May 1773 journal, when HMS Resolution sheltered in Dusky Sound about 250 kilometres south of Jackson’s Bay:

The most mischievous animal here is the small black sandfly which are exceeding numerous… wherever they light they cause a swelling and such intolerable itching that it is not possible to refrain from scratching and at last ends in ulcers like the small Pox.19

A hundred and two years later The West Coast Times wrote about the:

…good men… accustomed to the exigencies of such a life as they may be expected to lead in a bush-covered country… If there could only be discovered a panacea for sandflies, many in Hokitika would have good reason to envy the prospects of the pioneer settlers of Jackson’s Bay.20

Official niggles emerged within three weeks of the first settlers landing. Bonar’s urgent and positive letters to Atkinson pressing for haste in constructing roads, the tramway and a jetty did not receive a reciprocal response. The establishment of sawmills depended on a tramway to remove logs, Bonar said, and he reiterated the need for a jetty: off-loading steamers directly onto the beach in “even a moderate swell… would be a work of considerable risk, both to boats and cargo.”21

Fifty years later “work of considerable risk” continued at Jackson’s Bay. A Weekly News photographer captured this image of Paddy Nolan leading a Hereford stud bull ashore in 1926. The Jackson's Bay resident had bought the bull on a trip to the Southern Sounds and transported it on the government steamer Tutanekai, still anchored. (Photograph 002146 from the Hokitika Museum.)

Bonar responded that those labourers already in the settlement were “barely sufficient” for the “most urgent works required.”

Bonar’s desire for haste may have stemmed from his aspirations for his Westland province, little more than a year old when he wrote his first letters to the colony’s immigration minister.

Atkinson dampened Bonar’s enthusiasm. The government’s initial agreement with Westland to advance “a sum not exceeding £20,000… for settling and locating immigrants” turned into “only £12,000… available for all expenses connected to the settlement…”22

In the same letter, Atkinson told Bonar to stop sending any more settlers to Jackson’s Bay than were “actually necessary,” and that Westland’s shortage of labour at the time meant that losing men to Jackson’s Bay would “necessarily increase the cost and difficulty in carrying on the public works now in hand.” Bonar responded that those labourers already in the settlement were “barely sufficient“ for the “most urgent works required” as he was already “pushing on” the surveys and the road construction.23

Atkinson’s attitude reflected the settlement’s status during the next four years, which lurched from crisis to crisis until the commission of inquiry was established, and afterwards, settled into an inconspicuous existence.

_______________

In 1874, Bonar knew exactly the type of immigrants needed to tackle the steep hills and dense forests, and help set up timber, agricultural and fishing industries. As part of the ongoing Immigration and Public Works scheme, Bonar requested 250 families, the first 50 to be “experienced hands” from the West Coast. He wanted a “large proportion” of another 150 immigrant families from the UK to be members of the Agricultural Labourers Association. He requested Shetlanders specifically for their fishing knowledge and experience.

…recent gold rushes in the vicinity added a tantalising glow to advertising pamphlets… attempting to entice immigrants…

Pomeranians were to fill the final 50 places. Bonar heard they were “especially suited for such a settlement” from a local Pomeranian, Julius Matthies, who had spent a “considerable” amount of time exploring “our southern country,” and who seemed keen to encourage his own countrymen and women to follow him.24

Matthies’s report to Bonar oozes enthusiasm. Matthies believed the “proved failures” of previous settlements in Martin’s Bay and Stewart’s [sic] Island stemmed from “great inducements to acquire land” that depended “on only one branch of industry” and extolled Jackson’s Bay for its “advantages of successful agriculture, comparatively a near market, and riches of the sea.”25

Besides opportunities for agriculture and timber industries, recent gold rushes in the vicinity added a tantalising glow to advertising pamphlets written by government officials attempting to entice immigrants from the UK and continental Europe.

New Zealand’s agent-general in London, Dr Isaac Featherston, arranged a German translation of “books of general conditions of the settlements” for Matthies.26 It is unclear whether any of the Poles who arrived in New Zealand between 1872 and 1876 ever read the books—or met Matthies, who died in 1875.

… the 1879 commission listed those Poles as: Stobo, Shoplifski, Jaques, Pritzki, Shamlifski, Tobian, Rosanoski and Donitz.

Settlers trickled into Jackson’s Bay far more slowly than Bonar had anticipated. He waited in vain for his 150 British families with agricultural backgrounds and continued to complain about having “scarcely any immigrants for the settlement.”

A month later, eight Polish families and at least two German families landed in Jackson’s Bay. They had all arrived in Wellington aboard the Lammershagen on 11 July 1875. The Return of Settlers presented to the 1879 commission listed the Poles as: Stobo, Shoplifski, Jaques, Pritzki, Shamlifski, Tobian, Rosanoski, and Donitz. (Corrections and variances of their names are on the accompanying List of Polish Settlers in Jackson’s Bay.)

Bonar’s messages to Atkinson must not have been clear—or were ignored—because in March 1876 Atkinson used Westland’s “apparent inability to take more than a limited number” as his reason for not providing Bonar with immigrants. The immigration minister, however, said he “had reason to hope” that he could dispatch 400 adults there by the end of that year.

Bonar said he was “quite willing” to take German families if there were none from the UK and suggested 30 families from the Shakespeare be forwarded to Jackson’s Bay as “the German [sic] families already located are getting on very well.”27

By July 1876 immigration officers in Wellington admitted that although they were sending down nearly 40 “Prussians” to Jackson’s Bay “at their own request” the general demand for labour had dwindled, and “the foreigners… not nearly so readily absorbed and provided for as the British.”28

The settlers at Jackson’s Bay disputed the notion that there was a shortage of work. The promised jetty was not built, and neither were roads. (The light rail had long since been dismissed.) The unfinished track through Haast Pass, planned to link the South Island’s west and east coasts, still offered contracts. The settlers saw the logic of building sawmills among the timber. With their own sections not yielding much in the way of edible crops, they became desperate for jobs.

Rather than a shortage of work, the settlers believed that resident agent Macfarlane allocated the work unfairly.

Scotsman John Murdoch, who arrived on the first 1875 steamer with his wife and four children, testified at the commission that he averaged one and a half days’ work a week over three years:

Instead of the settlers getting work, it was withheld from them until their store account had run up… Work was given… to those settlers who were most indebted to the store… One of the reasons given by Mr. Macfarlane for not employing me was that he must employ those most indebted.29

Other settlers shared his frustration: Bartholomew Docherty asked Macfarlane for “equal justice” for the settlers in exchange for their withdrawing a petition against the settlement. Bartholomew said that for him, “equal justice” meant “equal work” but Macfarlane’s replied: “You can do your worst.”30

_______________

Wellington’s assisted immigration scheme from continental Europe collapsed 11 weeks after the Fritz Reuter left Hamburg with 292 immigrants when, on 30 June 1876, Atkinson wrote to Featherston in London: “I have now issued instructions that in future no foreign nominations are to be accepted except under very special circumstances.”31 On the day the Fritz Reuter arrived in Wellington—4 August 1876—Atkinson sent a telegram no agent-general could misinterpret: “Send no emigrants Jackson’s Bay special settlement.”32

Learmonth made a blatant admission that Jackson’s Bay provided the solution to Wellington’s difficulty in providing “foreigners” with employment.

Atkinson may have sent Featherston previous instructions, but the latter, then with failing health, may not have taken much notice. He resigned from office on 17 June 1876, and died in Brighton two days later. Sir William Powell, former director-general of the War Office, replaced him temporarily.33

Would Jackson’s Bay have succeeded if it received the promised 250 families, or if its administration honoured its pledge to provide two years’ part-time work for the settlers it did get? One cannot say, because neither happened.

Bonar’s plan to populate Jackson’s Bay predominantly with British people unravelled when he received a letter from immigration officer FA Learmonth in July 1876. Learmonth made a blatant admission that Jackson’s Bay provided the solution to Wellington’s difficulty in providing “foreigners” with employment.34 He blamed the continental Europeans for their inability to speak English, yet did not seem to question why his own government, when it first opened the colony to those same immigrants, had not considered more highly the ability to communicate in a common language.

Learmonth informed Bonar that of the 301½ adult immigrants who arrived in New Zealand the previous year, three-fifths were foreigners, with 124½ “German” (some were indeed German, but most were Polish). Bonar’s hoped-for British immigrants, Learmonth said, “were all of a very superior class to what was formerly sent to Westland, and soon found suitable employment [elsewhere] at fair rates of wages.”35

Clearly, Jackson’s Bay did not have the appeal that Bonar, his surveyors, and supporters like Matthies expected.

(The fractions above represent the method used to calculate fares under the assisted immigration scheme. Immigration officials classed anyone younger than 12 as equivalent to half a “statute” adult. They did not count anyone younger than a year, whom they classed as “souls” who received free passage.)

_______________

Would the Poles in Jackson’s Bay have fared better if Matthies had not died? The chief emigration agent in Prussia, a Mr Kirchner, reported to Featherston in August 1875 that his Berlin agents told him:

… notwithstanding all their caution, [Matthies] allowed himself to be entrapped by the Prussian police, and that, having acted in contravention of the laws, a bill was filed against him, and he was to have been committed to prison… the excitement produced apoplexy by pressure on the brain.36

Matthies left a widow and four children in New Zealand. With his death, the Poles in Jackson’s Bay lost an interpreter who seemed on friendly terms with administrators such as Bonar. They also lost a vivacious spokesperson.

Matthies’s September 1874 report to Bonar regarding the Pomeranians reveals his natural ability to persuade—and to stretch the truth. Among general praise for his compatriots, Matthies claimed that they came from a similar coast to Jackson’s Bay, and that they were accustomed to agriculture and fishing. He declared that the Pomeranians’ “great resemblance in manners and otherwise to the British nation, [and] close connection of language, would soon cause them to be amalgamated with the present population of the Coast.”37

Pomerania’s smooth coastline on the Baltic Sea in no way resembles the rugged West Coast and it was fanciful to insinuate that Pomeranians living under Otto Von Bismarck’s intense germanisation drive could speak English. Although the Polish translation of their collective name, Pomorzanie, means people from the coast, those those who arrived in New Zealand had lived inland and had been mainly farming serfs.

In 1876, the then immigration agent Theophilus Daniel of Riverton, Southland, begged Wellington to jettison the assisted immigration scheme in favour of a nomination system. Daniel, who later become mayor of Riverton and a member of the House of Representatives from 1881 to 1884, believed that overseas agents “considerably misrepresented” conditions in the new colony:

I have found recent arrivals… landed almost destitute of anything resembling suitable clothing for the colony, the articles brought out with them altogether useless… they appear to be under the impression that the colony was much further advanced than it really is.38

Under their contracts, emigration agents in Europe, such as Kirchner and Matthies, received £1 for every “statute” adult who arrived in New Zealand.

_______________

It was no coincidence that several of the first Polish settlers at Jackson’s Bay chose Smoothwater: those were the sections “thrown open” soon after they arrived in August 1875. Macfarlane told the 1879 commission that he had been “prepared to give them every information” and that he had called for tenders to build houses for them. It was also in Macfarlane’s interest to move new settlers from the free government cottages into their own sections as soon as possible—he could charge rent from the day a settler selected his own piece of land.39

“We did not sell the land, we simply left it… Mr Macfarlane was scolding my father for going away from Jackson’s Bay… I said the land was flooded, and we could not grow crops.”

Macfarlane contracted Canadian settler Albert Porter to build Franz Max’s house. Max, who described himself as “a farmer from my youth” but “no builder” asked another settler, the Scottish carpenter and plumber Robert Crawford, to inspect the workmanship on his behalf. Crawford found “bad” shingling on the roof, insufficient roofing battens, “badly” attached angle bracings, “badly” nailed weatherboarding, and—according to Joseph Max’s testimony at the 1879 inquiry—said that the house would “blow down when the bush was cleared” after which Macfarlane had “had some battens put to it.” Franz Max refused to accept the house. Macfarlane seemed surprised at Max’s fuss and told the inquiry. “I consider the house was worth worth the money charged for it.” Franz Max apparently sold the house to his neighbour Robert Lipinski and by November 1876 had left the settlement for Hokitika. Lipinski said he paid Mcfarlane for the house, which Macfarlane denied.40

The Smoothwater River soon showed its penchant for flooding. Mueller blamed the settlers for the stream’s “frequent overflows” that were caused by their felled trees falling into it.41 Macfarlane told the commission, “… the strip of good land was too narrow, and the fallen trees in the river caused the lands on the banks to flood; and besides it is very heavily timbered.”42

Flooding caused many settlers to abandon their sections, among them John Tobian and his son, Rudolf, on 10-acre sections 61 and 62 in Arawata South on 19 August 1875. They had a two-room house built on one section and, according to Macfarlane’s Land Report, had each paid £6 in rent. A tributary of the Arawata River flowed through both sections and Tobian senior told the commission that by August 1876, “We left the house because the land flooded and we could not get crops.” Two days earlier he had testified: “I could not keep occupation of it because of the water on it.”43 (Tobian’s wife and other four children are not mentioned in the reports.)

Rudolf Tobian testified: “We did not sell the land, we simply left it… Mr Macfarlane was scolding my father for going away from Jackson’s Bay. He said it was not right for him to go. I said the land was flooded, and we could not grow crops.”44

Mueller’s perverse criticism of the Poles for the flooding of their sections reflected the trend of those with vested interests in Jackson’s Bay: Surveying for the special settlement was lucrative; surveyors’ bills amounted to more than twice the resident agent’s salary. Number 13 of the General Conditions had assured the settlers that “experienced surveyors” would lay out sections. Those surveyors should have taken more notice of the terrain, and identified potential flooding problems.

Settlers had to clear land to create space for their homes and crops. Mueller’s chastising the Poles for doing exactly what they needed to do made little sense. The felled trees had to go somewhere. Some settlers used them to build dam walls. Floodwater scooped up the logs and created havoc on the narrow strip alongside the river. Mueller admitted to the commission that he had been “in a hurry” and had not visited Smoothwater until after the survey was nearly completed. He told the inquiry that “Browning’s recommendation was too hastily given” but would not admit his own role in encouraging settlement on what was clearly unsuitable land.45

_______________

Settlers’ submissions at the commission portrayed a haphazard granting of contracts by Macfarlane, not necessarily to the cheapest tender, nor to those best qualified, and several repeated the Scotsman Murdoch’s assertion that Marfarlane chose who would get contracts by how much they owed to his store.

Substandard engineering resulted from different people working on the same sometimes small contract, coupled with Macfarlane’s apparent inability to listen to settlers’ complaints or suggestions.

Another of the first Scotsmen, Thomas Beveridge, was also frustrated by substandard engineering work. On 9 March 1875, he had the misfortune to take up section 70 in Arawata South. Pole Michael Gdaniec became his neighbour on section 69 five months later. An 1880 map shows sections on both sides of Arawata Flat Road, and numbers 69 and 70 not far downstream from where a significant tributary of the Arawata River crossed the road, built in 1878. A smaller tributary ran across an intersection adjacent to Beveridge’s property and through both pieces of land.

A close-up of the 1880 map that shows Thomas Beveridge’s and Michael Gdaniec’s sections among others south of the Arawata River. The Arawata Flat Road headed towards the bay, and joined an unnamed road along the coast that led to the township.46

Beveridge had paid £7 10 shillings in rent, had had a house built, and had cleared at least an acre. Macfarlane’s Land Return shows that there was also a house on the Gdaniec property, and that half an acre had been cleared. Beveridge told the inquiry that he had paid particular attention to a bridge being built across the creek above his property because it affected not only his land, where he lived with his wife and six children, but also his access to the road to Jackson’s Bay.

Beveridge to the inquiry: “The road to Arawata is not as it should be. A great many chains are being washed away for want of a culvert. Next to that there is a bridge across the creek stopping up the water from the creek, and destroying the road and my section as well. … There is a two-foot drain that takes away the water about forty chains along the road, not half big enough for the purpose.”47

One chain covers a distance of about 20 metres. The bridge, instead of allowing water to flow under it, became an unwanted and unstable dam upstream of Beveridge’s section.

Antonio Max’s testimony to the inquiry showed that he took up a section at Arawata South after he heard that land in Okuru was prone to flooding—but problems with flooding were just as bad in some of the Arawata sections. The small amount of drainage built in the settlement seemed to do no more than move a flooding problem from one place to another. A drain built through Antonio Max’s neighbour’s property, for example, ended at their common boundary, flooded Max’s land, and denied him access. After three years, he gave up. He told the commission:

I thought I should get good land. I was told so before I came to Wellington and Hokitika. That was the reason I came… I have tried to make my home here, but I cannot see that I can. If I were certain of getting work here I would remain. I am married with five children. If I can get a passage [back to Hokitika] I will go. I cannot stay unless I can get work to provide myself with necessities for my family.48

Redoing work became a matter of course. Mueller distanced himself from the wire bridge across the Turnbull river that was carried away by flood. It is not clear who received the contract to retrieve the material and rebuild it, but again, the structure did not last49

_______________

Some Hokitika residents clashed publicly with officials at the town’s wharf on 5 February 1876, in support of Poles who, after hearing negative reports, did not want to be forwarded to Jackson’s Bay.

Those Poles had spent 109 days at sea aboard the Shakespeare, which sailed into Wellington Harbour on 23 January 1876, and quarantined on Matiu/ Somes Island until immigration officials passed them fit eight days later. On 9 February 1876, The West Coast Times reported that 56 Shakespeare passengers were transferred to the steamer Wallace, bound for Hokitika, and were “at once transhipped” to the Waipara and Jackson’s Bay.50

Peter Helming, a mechanical engineer living in Hokitika, happened to be at the wharf that Saturday evening. He told the inquiry that he saw that he saw “women and children were crying and wishing to go on shore” but not allowed. (Helming and another witness, Herman Meyer, recalled the steamer from Wellington as the Murray and not the Wallace. Both were used on the route by the Anchor Line.)

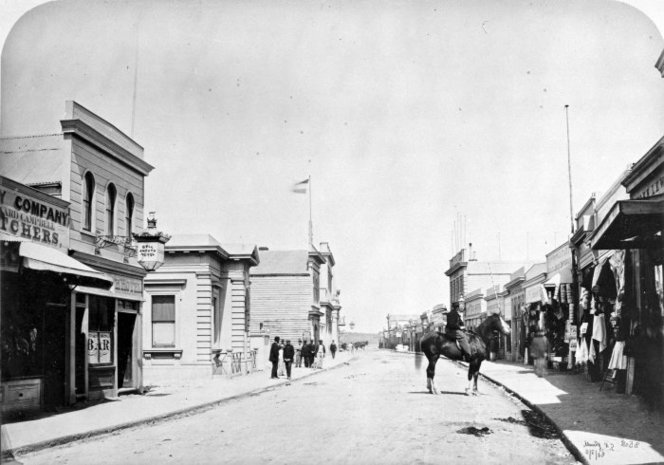

Daniel Lewis Mundy took this 1868 photograph of Gibson’s Quay, Hokitika. West Coast New Zealand History says that by 1866 it was one of New Zealand’s “most populous” centres, and that on 16 September 1867, there were 41 vessels alongside the wharf.51

… his reason for giving evidence… was “[T]o show that compulsion was put upon the immigrants… to try to force them to go to Jackson’s Bay.”

Judging by events on the evening of 5 February 1876, the Waipara was alongside the wharf behind the steamer from Wellington. Learmonth and Bonar were on the wharf. Bonar told Herman Meyer, a hotelkeeper in Hokitika who acted as interpreter, “to tell them that they were not bound to go [to Hokitika]; that they could go on shore and stop here, but they had to provide for themselves but, if they went to Jackson’s Bay, the Government had built houses for them, and they would get work, as was in the pamphlet which they had, and also fifty acres of land.” Meyer testified that the new immigrants had started to move their luggage into the Waipara when they were stopped by “several other Germans [who] came up and tried to dissuade them from going to Jackson’s Bay, as the settlement was no good.”52

Eight single men, aged between 21 and 35, abandoned any luggage they may have had in the steamer’s hold, “threw the small swags they had” towards the wharf, and disembarked despite an order not to. The captain of the Waipara noticed them, and moved his vessel between the Murray [or Wallace] and the wharf to block other passengers from following. Helming saw the last man jump off the steamer as the Waipara was “slewing around [and] her stern touched the wharf. Bystanders on the wharf reached their hands to help the man coming ashore, to prevent him going overboard.”

Hokitika drapist, a Mr Davidson, and tobacconist, a Mr Apple, both asked Bonar to allow the men into the immigration barracks, but he refused. Helming questioned the men, who told him that they wanted not land, but a share in the “plentiful employment” they were promised in Hokitika. Peter Helming discovered that among the eight were a shoemaker, a baker and a butcher, and that the only Pole to make it ashore—labourer Frederyk Grazewski, 34—moved on to Greymouth. The commission spelt his name “Grafansky.”

Helming: “They asked me if they were compelled to go [to Jackson’s Bay]. I said, ‘You are in a free country, and you can do as you like.’” After finding out that the men were refused entry to the immigration barracks, Helming invited them home for dinner.

Helming, at one time an inspector of works for Mueller, said his reason for giving evidence at the commission was: “[T]o show that compulsion was put upon the immigrants… to try to force them to go to Jackson’s Bay.”53

Herman Meyer, a hotelkeeper in Hokitika, acted as interpreter that evening on the wharf. He told Learmonth that the Poles were under the impression that they would each receive 50 acres of land in Hokitika. Meyer said they seemed satisfied regarding his explanation that Jackson’s Bay was “only another part of the province” and they agreed to continue south.

Once the Poles on the Waipara got to wharfless Jackson’s Bay—so different from Hokitika—it did not take them long to confirm what they heard in Hokitika of their compatriots’ wretched lives there. If this was freedom in New Zealand, it seemed worse than what they had left behind in Prussian-partitioned northwest Poland.

It is not clear how The West Coast Times counted the 56 Poles involved, but the newspaper reported that 24 “statute adults” returned to Hokitika. The Osiowski (Osofski, Offsoski) family of seven was among the few who landed in Jackson’s Bay and stayed. Several other men and Anna “Zylifski” (Czuglewski) ventured ashore and spoke to people there.

The Shakespeare Poles’ refusal to land in Jackson’s Bay led to an immediate inquiry chaired by Bonar and Learmonth in Hokitika.

_______________

Polish settlers already living at Jackson’s Bay were on beach when the Waipara arrived that February, and told Józef Stachurski they had no doctor, and it was “impossible” to live there. Pushed by Learmonth at the inquiry, Stachurski said that the settlers told him “everything was very dear” that they “could not do more than pay for their provisions” and that they “must live like wild beasts.” Another told him that “it was quite impossible to cultivate mountains, which for half the year were covered with snow.”54

Stachurski, through a translator: “We expected to see a town or village, and, on account of not seeing one, we got frightened.” Stachurski, husband of Anna (née Szreder) and father of Maria (5), Józef (2) and Rosalia, born at sea, nearly did not make it back to the Waipara. The West Coast Times reported that, “Coming back, he jumped into the water, and was nearly drowned.”55

In Hokitika, Bonar asked Stachurski what he expected to do.

I will do anything. I do not want to stay in the barracks. I would rather go away to-day than to-morrow if I could only get work. I am willing to work at once.56

Bonar to the interpreter:

Tell him he has thrown away a very good chance of getting a permanent settlement in the country, and that they cannot remain here [Hokitika immigration barracks] more than a few days. If they refuse the Government offer, the responsibility must rest with them.57

The interpreter replied that Stachurski’s impression from officials in Wellington was that the settlers would find accommodation and work in Hokitika, and that they had never heard of Jackson’s Bay.

Bonar:

The Government had gone to great expense in order to send them where there was work to do, and they have deliberately refused it. That is what I want them to understand.58

Bonar did not appreciate Stachurski’s response that people in Jackson’s Bay told him they worked there, and starved there:

You may tell him that there are 200 or 300 people there, and that there are plenty of applicants from the Coast who would be glad to go on the same terms, but we have been keeping it for the foreign immigrants coming into the country. We have refused hundreds.59

Stachurski said he spoke to settlers who wanted to leave but could not, and told Bonar and Learmonth that he saw women crying.

The rest of the inquiry into why the Shakespeare immigrants refused to land at Jackson’s Bay became a repetition of the above exchange, those presiding over it generally disbelieving the immigrants’ statements.

Mueller participated in the Hokitika inquiry in his capacity as provincial engineer. He disputed the statement of another Pole the newspaper named Schardrovski—possibly one of the brothers Joseph or Anton Szczodrowski—through the interpreter Mr Robeck.

According to The West Coast Times summary of proceedings on 9 February 1876:

Those that were down there were running about badly clad, and they thought they could not have earned sufficient to provide sufficient clothing for themselves. Some of them had seen some whom they knew at home, and they were going in rags. They got provision from the overseer, but it was not enough; they had nothing to buy clothes.

Mr Mueller remarked that there must be something radically wrong in the [witness’s] statement. The Germans [sic] had not been working three days, but six days, receiving 48s, and as their expenditure could not be anything equal to it, they must have pounds in Mr Macfarlane’s books. They must have from 28s to 34s per week.60

Mueller seems to have been the only person to believe that the settlers had six days’ employment per week.

Anna (née Fiatek) Czuglewski returned to the Waipara without her husband, Frederyk. (Spelling variations of their surname included Ziglefsk, Zilawski, Zyglensky Zylifski, Zylawsky, and Zyglewski.) She told the inquiry that the Shakespeare Poles had expected to stay in Hokitika and were “removed without being consulted” to Jackson’s Bay. She said that she was not used to “such a wild-looking country” and refused to return.

She knew that at Jackson’s Bay they got 8s a day for three days per week, but they must drink tea three times a day, and likely to get into debt. As soon as she went ashore she found a woman who had been in service with her, and as soon as the woman saw her she commenced to cry, and asked her if she was one of the unfortunates ones to come there. She then told her that they were in debt, and would never come out of it till they died. They did not say they did not get enough to eat, but clothes were such a price that they would not pay for them. What cost tuppence at home cost two shillings there. She repeated she would not go to Jackson’s Bay; her husband must come to Hokitika.61

Weronika (née Majewska) Bielski said that she and her husband, Walenty, immigrated to New Zealand “in consequence of the glowing accounts they heard of the country.” She did not go ashore with her husband and two of their three children, who were not allowed back on board the Waipara. She heard from other passengers about settlers in Jackson’s Bay being so much in debt that she “would die here” [Hokitika] rather than go to there.

Johan Senger did manage to re-board the steamer after he explored the Jackson’s Bay “mountain… The scrub you couldn’t get through, and you couldn’t look over.” He did not see any clearings or homesteads:

He was told that there were settlers that earned 24s per week for three days, but it just covered the cost of their provisions. He was told they could work on their land for the rest of the time, but that the settlers had not taken up their land, as they could see it was not worthwhile troubling. People in Hokitika told him not to leave the steamer… After that they formed the intention not to stay at Jackson’s Bay. They intended to stay in Hokitika… If the Government could not give them work here, they should send them back to Wellington, and, if not at Wellington, they should send them back to Prussia.62

The interpreter’s repeated use of the description “wild-looking” reiterates the assertion by immigration agent Theophilus Daniel that people arrived in New Zealand expecting a more progressed colony. The Poles may have come from a culturally oppressive society, but continental Europe lay within many hundreds of years’ civilisation, where people did not have to hew shelter from a surrounding forest, and where even the poorest peasant could cultivate basic vegetables.

Immigration minister Atkinson reported the Shakespeare incident to agent-general Featherston in March 1876, saying he enclosed a report from Bonar regarding the reasons for the refusal, but that report is not with the other enclosures in the parliamentary papers.63

Two photographs of beachfronts—Hokitika's Revell Street, above, in 1868 and below, Jackson's Bay, more than 300 kilometres south, in 1880. Daniel Louis Mundy photographed Revell Street64 (Photograph from the Alexander Turnbull Library) and James Ring took the one below, captioned “Jackson’s Bay looking north.” The Grafton is in the bay and the unidentified men and cargo would have come ashore on the dinghy.65 (Photograph 002147 from the Hokitika Museum.)

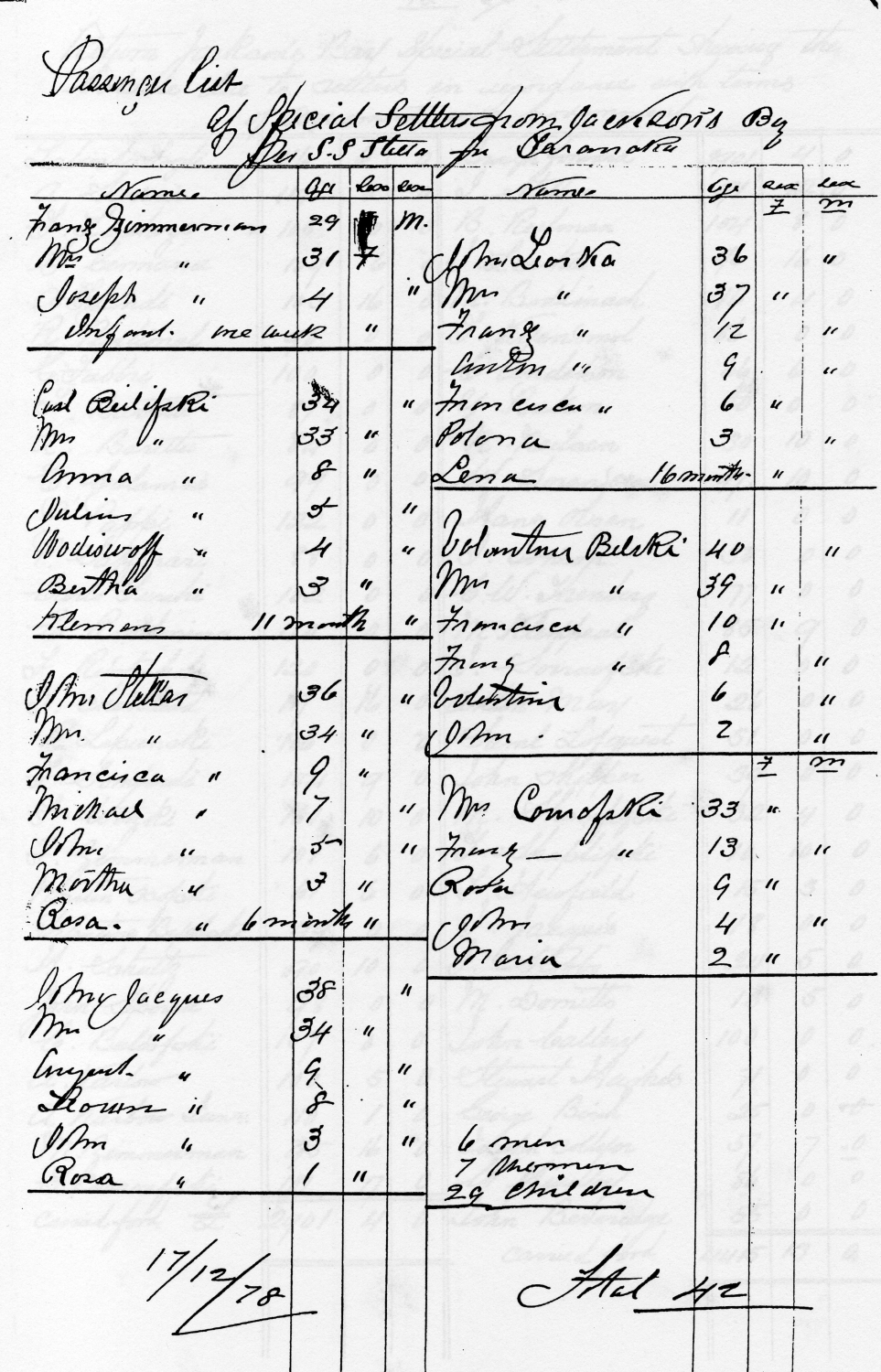

Despite negative rumours, more “foreigners” did arrive at Jackson’s Bay in 1876. These included two groups of around 25 and 35 Italians—off the Herschel, Shakespeare and Gutenburg—who had planned to grow grapes and vegetables in Okuru, the Polish immigrants off the Terpsichore, and the Kurowski and Lipinski families off the Fritz Reuter. Franciszek Kurowski drowned with five others on the way to a prospecting expedition south of Jackson’s Bay in June 1878. Their boat “deeply laden with crowbars and other mining tools, which had been taken to Jackson’s Bay for sharpening” was believed to have been swamped by a giant wave that formed off a reef between Martin’s Bay and Big Bay.66 His pregnant widow, Franciszka, née Kamińska, and their four children—Franciszek (13), Rosalia (9), Jan (5) and Marianna (2)—left Jackson’s Bay that December and settled in Taranaki. (See The Kurowski-Crofskey Family and The Fritz Reuter stories.)

Although both Anna Czuglewski and Weronika Bielski told the Shakespeare inquiry they refused to return to Jackson’s Bay, both did. Anna gained notoriety as the woman involved in an altercation with Macfarlane and his storekeeper, Scotsman Adam Crone. Macfarlane had given Crone instructions to refuse her provisions. When told she may not have a bag of flour, she went behind the counter to fetch one. It is not clear how many men it took to remove her from the shop, but she landed on the ground outside—without the flour, and the door closed.67

The official list of settlers shows that Frederyk “Zylifski” left Jackson’s Bay in December 1876, Martin Osiowski and his family left in October 1878, and Walenty Bielski left with his family in December 1878.

_______________

Diametrically opposing views regarding the Jackson’s Bay settlement continued to make headlines as protagonists wrote to editors. Officials like Macfarlane labelled the settlers who complained as lazy and ungrateful, and accused them of trying to cheat the system.

Macfarlane voiced his displeasure of his critics by calling them “scurrilous pens… used for the purpose of damning the settlement right through.”68

“Special Settler” wrote to The Otago Daily Times on 6 January 1876:

… we are for the last two months, owing to non-appearance of the S.S. Waipara, almost out of provisions. The S.S. Maori, from Dunedin, has been here four times since the Waipara, and only brought a few tons of goods, and the consequence is, we have had to live chiefly on flour and tea. A telegram was sent from Hokitika, via the Bluff per S.S. Maori, early in November, stating the Waipara would be here on the 18th of that month, but did not come. The Maori was again here on the 17th of December, and brought five tons of goods, including one bullock, for about 200 people, and also the news that the Waipara would be here in four days. From that date, which is three weeks ago today, and no steamer, and the only way we have of making our grievances known is through the Press. We have to pay a very high price for our things. Dunedin flour, £18 per ton, inferior potatoes, £14 per ton; meat, fresh, 8d per lb; preserved 10d, when attainable, which is very seldom—that is meat and potatoes. A great many of the settlers have land cleared for potatoes, but could not get them, and the ground lying cropless. Such is the state of things at this settlement. Captain Malcolm, of the S.S. Maori, informed me some time ago that he could land flour here at £14 per ton, and potatoes at £6 per ton; and he also sold some fresh meat to the settlers at 6d per lb. But most of the settlers are in debt to the Government store, and, receiving no money for their labour, could not avail themselves of the chance.

… We have regular steam communication between Dunedin and Jackson's Bay, and provisions are at least thirty per cent cheaper. This is a material item to settlers with families, who, by their agreement, only receive 24s per week for two years. Some of the settlers have been here now nearly one year, and the rural land was only open for selection on the 3rd inst., after taking nine months to survey for one hundred and twenty 50-acre farms, and, nine-tenths of them under water; in fact the whole block set aside for settlement. From the Arawata to the Haast rivers is nothing but a succession of lakes and lagoons. I do not think there will be ten sections taken up by the settlers here. They have most of them erected houses on their 10-acre sections, and the opinion of most of them is that they have nine acres too much now. The road that runs from the bay to Arawata river—a distance of seven miles—about five miles are cleared of bush, and 25 chains of it formed. This is all the work done in the settlement up to the present time. We have a fishing company started here, but it is expected to meet the same fate as the coal mine there was so much blowing about by the Resident Agent, but turned out nil. They did not get as much coal as would weld a pick, after six months' prospecting.69

The Grey River Argus, after the editorial below, published two more letters from settlers on 18 March 1876:

The Jackson's Bay Settlement is attracting considerable attention, not on account of its favorable [sic] condition, but on account of its entire unsuitability and alleged mismanagement. Of course its promoters and the Resident Agent endeavor [sic] to make the best of it, and generally deny the truth of the numerous complaints that have been made. This is but natural. It is not likely the Resident Agent would do otherwise, considering that his situation depends upon the continuance of the transport of deluded people to the place. An elaborate defence written by him, in reply to the letters of Mr Hoos in the New Zealand Times, appears in the West Coast Times of yesterday, which, with the private information in our possession, we cannot accept, unless with a considerable amount of salt. A person, not a settler, but who has been down to the settlement for purposes of his own, and who has just returned, gives as [sic] a truly pitiable account of the condition of the settlers. He says that there is no land worth anything; where it is not swamp it is sand or shingle, and that when cleared it is useless for cultivation. The case of the women and children is described as melancholy in the extreme. The heads of families can earn barely sufficient to procure the necessaries of life, and their wives and children are going about bare-footed and ragged, unable to purchase needful clothing, and are generally in a miserable condition. We have received two letters from the settlement, which we publish below. Some of the statements may be exaggerated, but it is patent that unless the settlers are to become paupers on the State, the settlement will have to be abandoned.

“One of the Deluded” wrote on 6 March 1876:

The wilful and disgraceful waste of public money in this place at present, ere long, will be something to be deplored. The whole settlement, from Jackson's Head to the Haast, for agricultural or any other purpose, would be dear at [£]5, bought in one lot. The whole is one mass of rivers, rocks, shingle, swamp, and impenetrable jungle…

… I say this place is wrongly represented. The man that wrote that pamphlet regarding the capabilities of this jungle and eel pond was like Tom Bowling, he could spin a good yarn. It is in every way calculated to deceive the public. The place is not fit to turn out wild pigs on. The most of us are heavy in debt for our tucker, and half starved at that, and how we are going to pay I don't know.

Part of another lengthy, undated letter from “A Settler”:

The pamphlet published by the authority of the Government stated that provisions would be supplied at cost price. Now, our interpretation of the word cost price was that provisions would be supplied to us at a lower price than Hokitika general retail price. No one would have attempted to come to settle and work at Jackson's Bay for one shilling an hour had they known that all their earnings would be required to keep them in the rough necessaries of life. Touching the description of the country given in the pamphlet, it is not the paradise that it has been painted. The land put aside for settlement was said to be clothed with the luxuriant growth of fern trees, whereas it is an impenetrable forest of red birch, and that it is of no earthly good, with a dense undergrowth of bush lawyers…

… we were hunted out of the Bay in the worst part of the winter, without a house to put our heads in, and compelled to build huts and clear bush on these small blocks of land that would not support one man throughout the year.

… the result of this arbitrary act of the Resident Agent in compelling us to make improvements on these small blocks of land, is that twelve months labor [sic] has been thrown away on useless land, and we are now too poor to take possession of the 50 acres and pay the rent.

… Had the settlers been treated with justice they would have been allowed to continue to work on the road till the 50 acres were open for selection, then we would have been in a different position to what we are now—that is, we would not be in debt.

… and those unfortunates that dared to insinuate that provisions were not sold at a fair price were punished that is, if we may judge by the small amount of money that they were allowed to earn in comparison to others.70

Edmund Barff was re-elected to the House of Representatives in 1876. As editor of The Evening Star, Hokitika, he received several letters from Jackson’s Bay settlers.

“A Digger” wrote, “There is favouritism here… Some men are always at work; others are not.”71

One of the earliest letters Barff received came from digger James Teer and referred to the Shakespeare incident:

… you have heard of the landing of the German “convicts,” as they are called here. The scene on board the “Waipara” was one of the most disgraceful ever witnessed in a civilized community, and will be a lasting shame to Westland, if not to New Zealand. It was very fortunate that the present officials here had not many friends on board, or I am afraid there would have been bloodshed in trying to force the deluded unfortunates on shore. The captain of the “Waipara” personally tried his utmost with his own hands to put them on shore, but soon found out that he had not strength enough, and was forced to let them remain. No doubt they have found out from some of their countrymen of the swindle—for this place is nothing but a complete public swindle, and a useless waste of public money…72

The settlers continued to write to Barff both in his capacity as editor and as their representative politician. One of the last letters came from “A Settler” who in April 1876 complained that “we are now denied writing material at the store; we are told there is none.”73

__________

Allegations of not only expensive but also inferior goods supplied to the settlers threaded through submissions. Irishman Bartholomew Doherty, another of the first settlers, complained about the “bad” oatmeal and flour.

Eighty years later Frank Heveldt remembered the state of the flour. His parents paid full passage from Hamburg on the Lammershagen. They moved to Jackson’s Bay independently a week later, and took up a section next to the Tobians in Arawata. Heveldt’s 1961 interview with Radio New Zealand features in Julia Bradshaw’s book The Far Downers, The People and History of Haast and Jackson Bay. Frank’s boyhood memory of the Jackson’s Bay store:

All the damaged cargo was sent [to Jackson’s Bay] and we had to take it or leave it. I remember going in, my mother and I, to get a fifty [lb bag] of flour and there was a lot of it on the counter… and you wouldn’t know it was flour—it was just a big heap of weevils. If it wasn’t for that I wouldn’t remember anything about it, but it was seeing these weevils rolling, that impressed my mind. We paid top price for it. We had to carry that stuff out six miles on our backs, there were no horses. When we tried to bake it—well, you might as well go out there and get the mud out of the gutters, there would be as much rising in it as there was in that flour. It wasn’t flour at all, it was just weevils and we had to take it or leave it.74

Newspapers regularly reported the sailings, expected arrivals, passengers, and “exports” taken to the various West Coast and Otago settlements. Steamers calling in at Jackson’s Bay often had to wait for rough weather to subside before coming in, but it is not clear why the store’s produce was sold in such bad condition, or why there seemed to be such a lack of goods. The West Coast Times reported on 1 April 1876, for instance, that the Waipara offloaded: “75 packages of ironmongery, 27 cases, 20 sheep, 5 pigs, 2 bales leather, 500 bricks, 5 bags salt, 290 [bags] flour, 6 [bags] oats, 10 [bags] wheat, 40 [bags] rice, 6 cases kerosene, 12 boxes candles, 29 pkgs groceries [no further description of what the possible packages may have contained], 19 bags sugar, 12 chests tea, 10 kegs butter, 2 cases gunpowder, 2000 caps, 2 cwt shot.”75

Settlers in Jackson’s Bay provided the government store with a captive market— thanks to having their salaries paid by cheques that were only redeemable at the store. Rivalry between provinces at the time contributed to higher costs for goods landed in Jackson’s Bay from within Westland than from Otago, but it was not in Westland’s interests to have Jackson’s Bay receiving goods at Dunedin’s competitive prices.

A surveying party in Hokitika employed Jakub Czaplewski and paid him £10 10s—by cheque. Macfarlane’s authority as “countersigning officer” for such cheques allowed him to retain any money settlers earned on surveys, and forced the earners to redeem their wages by buying goods from his store. This is exactly what happened to Czaplewski, leaving the Pole again without the ability to buy cheaper goods available from anyone else.76

The Pole soon became ensnared in the store’s accounting system and told the 1879 commission he was “surprised” when access to his own “pass-book” was denied him at the store.

I wanted clothing for my children. Mr Macfarlane refused to give me any, and their clothes were so ragged I could not send them to school. All the time I have been here I have not been able to get clothing for my children. All the covering I could get for them was old flour bags. I did not like to see my children going to school so badly clothed…77

Three of Czaplewski’s six children were school-going age when the family arrived in August 1875. (His surname in Jackson’s Bay was misspelt Shoplifski, Shaplifski, Chablaski, and Chabalaski.) The family lived on section 67 in Arawata, where they had a house and had cleared three acres, but where their potato crop had failed for three successive years. He told the commission:

… the provisions were charged for in the store too high… [goods] could have been got here for half the price. I wanted some potatoes. [T]hey were sent to the Arawata by the boat. I came to fetch the potatoes from the shed at the barracks. I emptied the bag and picked over the potatoes, and I had to leave half of them there rotten.78

Potatoes spoilt in the ground all over the settlement, and other produce, such as swedes, turnips, and oats, gave low yields. Settlers lost their first and second crops. The hurried hunt for more seed potatoes from Hokitika late one season became a blaming fiasco that covered many pages of the commission’s 1879 report. Bonar and others dismissed accusations from the settlers regarding attempts to fob them off with rotten, overpriced potatoes.

“The price of goods was so high that it was impossible to keep out of debt,” Robert Crawford told the commission. As well as food, Crawford referred to carpentry tools being more expensive in Jackson’s Bay than in Hokitika. Appointed postmaster of Jackson’s Bay in June 1875, Crawford resigned when his business became embroiled in Macfarlane’s accounting system.79

Nearly 150 years after the first settlers arrived in Jackson's Bay, its steep hills, thick bush and harsh climate still make this a tough lifestyle choice.

_______________

By 31 March 1877, resident agent Macfarlane had spent more than £17,500 of the original £20,000 allocated to the settlement (or had overspent by £5,500 if the revised allocation is used).

At more than £10,000, labour costs topped the expenses. Settlement accounts presented at the commission by Edward Patten—who took over from Bonar in July 1877—show spending for building Macfarlane’s house, offices in Jackson’s Bay and Okuru, 50 kilometres of roads, and the beginning of a jetty. Continuing surveys cost more than £3,000. Macfarlane’s salary “and all necessary tools and appurtenances for works” amounted to nearly £1,300.80

In his 21 May 1877 report to the (unnamed) Minister of Immigration in Wellington, James Bonar—as Executive Officer, Provincial District of Westland—stated his satisfaction with the settlement’s progress “in spite of the very great difficulties” resulting from its “isolated position” and its “natural disadvantages from its being unsettled bush country.”

Bonar placed the blame on the settlement’s not advancing at a faster pace on “above all, the fact that instead of being populated by the class of immigrants originally intended when the settlement was projected—namely agricultural labourers from England and Ireland, and men accustomed to fishing from the north of Scotland—it has become an outlet for Germans and Poles unable to find employment in other parts of the country, and Italians whom the Government had for months in the depôt in Wellington, all of whom were unable even to speak the English language…”81 He did not seem to consider that the rainfall and terrain would have prevented settlers from anywhere in the world from growing decent crops, that they would still have had to compete for the few available jobs, or that they would also have been hindered by the lack of a jetty.

Bonar’s 1877 balance sheet showed that until then, £15,159 had been “expended” on the settlement. A further £2,372 represented “unsold stores in hand and the amounts owing by settlers” but it did not give a value to the unsold goods, or state whether the settlers owed money to the store, or for rent.82

Bonar described a “settled population” of 376 people who he said lived at six different points within the twenty-mile length of the settlement, but his enclosure from Macfarlane mentioned four: “German Poles have settled in the Smoothwater Valley; the Arawata is occupied by a mixed community of English, Scotch, Irish, German, and Canadian; Waitoto by Scandinavians; and the Okuru principally by Italians.”83

The Macfarlane house, and “family group” with tennis rackets.

(Photograph no. 006599 from Hokitika Museum.)

Written on the back of this photograph are the words: “grandfather’s store at the left and the family home at the right with tennis court.” The “grandfather” was resident agent Duncan Macfarlane, and the two buildings were on opposite sides of Pier Street, the store on the left facing the sea. The government houses first built for settlers between the store and Macfarlane’s house in 1874 were long gone. Judging from the extent of the slips, and the fact that it is a rare elevated photograph of a remote region, it could well have been taken by a photographer who climbed the nearby hill after the landslips of December 1886, when five days of rain led to flooding, and the saturated mountains disgorged masses of trees, mud, and debris. (Photograph no. 006600 from Hokitika Museum.)

In January 1878, Englishman John Marks, who had previously run stores in Haast and Okuru, and who had 250 acres in Haast in 1877, took over the government store from Macfarlane and Crone. German John Malam, who had a beach-front section at Arawata South, was running a ferry service across the bridgeless Arawata River—a tenuous link between settlers in Arawata South and Waitoto. James Nightingale’s position as Overseer of Works kept him in permanent—and influential—employment. Butcher Charles Robinson supplied the store—yet another butcher, John Love, could not trade after he asked for payment in cash. Nightingale, Robinson and Love were all from England. At the time of the December 1886 rains, floods and landslips, Robinson was keeping the township’s Royal Hotel.

The Jackson’s Bay correspondent for The West Coast Times, who seemed to be staying at the Macfarlane house, wrote on 10 December that year about the four-day downpour that led to the hotel’s ruin, and the death of the Robinson’s eldest child:

The visitor to Jackson’s Bay, arriving before this catastrophe, could not fail to be improved

with the peaceful, pleasant appearance of this sheltered spot, with its neat and well tilled gardens and green paddocks,

which are now nothing but heaps of mud, boulders and logs.84

While Robinson and his 13-year-old son were trying to divert the flood away from the back of the premises, “an

enormous mass detached itself from the mountainside and swiftly bore towards them.” It knocked down Robinson and washed

the boy towards the “seething mass of foam” that was the sea. The correspondent noted that the area’s

“complete isolation” meant that settlers living just a few miles north had no idea what had

occurred.85 Years after Resident Agent Macfarlane criticised the Polish settlers for flooding their sections at Smoothwater, and

Beveridge for complaining about the damming up of the culvert above his property, this incident showed that no one was immune

from the effects of torrential rain on even the most benign stream. More from the same correspondent’s report: The only way we can account for such immense masses being carried down by such a small stream

is by supposing that slips occurring near the exit from the gorge had blocked up the creek till the accumulated waters at

length broke the barrier, carrying it along with them in their course. In the settlement’s early years, the Albert Porter who built Franz Max’s house in Smoothwater received a contract to build

other cottages for the Poles there. He also ran a “small store,” although it is not clear where. He and a Milton

Porter took up sections in Arawata South in March 1875, and a year later they both also had sections in Waitoto, adjoining

those of a Fred and William Porter. An Amos Nicholson, not on the list of settlers given to the inquiry and nor on

Macfarlane’s 1880 Land Return, became manager of the only sawmill. Englishman George Adams, a former miner who took up a