Madeline Orlowski Anderson

Madeline Anderson sounded much younger than her 110 years when John Campbell of RNZ interviewed her two days before her birthday on 4 May last year.

The oldest person in New Zealand told John how “terribly lucky” she felt, how she still enjoyed communicating with people and that during her life New Zealand had become a “wonderful country.”

John called her “sharp as a tack.” I agreed and thought I could take some lessons from her positive attitude. When I saw a photograph of her on the Polish Embassy website with Polish Ambassador Zbigniew Gniatkowski and his staff, and realised she had a Polish father, I hoped she may like to tell her family story for this site.

Franciszka and August Orłowski, stepped off the palmerston in Port Chalmers in December 1872 with their baby, Mary. Their two-year-old, Franz, died on the voyage.

Franciszka and August settled in Waihola and had nine more children. Madeline's father, John Andrew, was the fourth and the second son.

When I spoke with Madeline at her Upper Hutt home she had just come out of hospital. We arranged that her daughter, Heather List, would be her voice but was not needed as much as we expected: Madeline still contributed strongly.

Madeline is the oldest and last surviving of four sisters, who remained close throughout their lives.

Madeline now lives in Masterton with Heather and her husband, Robin List. One of the many callers wishing Madeline a happy 111th birthday was her second cousin, Ken Luskie, who visited her earlier this year from Australia and took this photograph. Madeline had shown them the doll that she received for her fifth birthday. Apart from a second dress, the doll, Dorothy-May, has weathered her years as well as her owner.

My appreciation and best wishes to Madeline and Heather, who scanned numerous notes and photographs and who read my draft to her mother, whose failing eyesight caused her to stop playing bridge at 102 (she could see the cards in her hands but not those on the table).

—Barbara Scrivens

CENTENERIAN CONFIDENCE

by Barbara Scrivens

Her failing eyesight forced Madeline Orlowski Anderson to stop using a personal computer shortly before her 100th birthday a decade ago.

During her 110 years, Madeline allowed few things get the better of her, but when that machine failed, she accepted that her eyes were nudging her to retire gracefully from the digital technology she had embraced as seamlessly as she had the newly installed telephone in her maternal grandmother’s home in the early 1900s.

A relative employed as a maid was afraid of the brown machine on the wall. She used to lift Madeline on a chair so the little girl could reach and hold the device for her.

“You had to ring it on the wall. She was afraid of it, so she made me handle it.”

Fear did not feature in Madeline’s vocabulary, nor that of her younger sisters, Rayena Hazel (born in 1909 and named after her father’s maternal grandmother), Mavis Ethel (born in 1911) and Gertrude Jeffrey (born in 1914 and named after Mrs Jeffrey the midwife).

Builder John Andrew Orlowski adored and indulged his four daughters. They loved him back.

When he happened to be building a house in Wanaka, and had already employed 15-year-old Mavis to cook for the workers, Madeline took a break to join them and also visit two friends who lived in Wanaka.

One day the four girls used John Andrew’s car, a Crossley, to visit one of the friends’ relatives at a station in Glenorchy, on the far side of Lake Wakatipu. They planned to take the steamship tss earnslaw from Queenstown.

Mavis, the bossiest and most capable of the sisters, took the wheel and drove through the Crown Range towards Arrowtown. The brakes failed on the way down the treacherous road, but Mavis managed to control the car, driving it to Arrowtown, and then Queenstown.

The sun had set by the time they started their return trip, this time through the longer route following the slightly less winding Kawarau Gorge road. They were not put off by the man who, when he found out that the four planned to return in the dark told them, “If you're going to drive through the Kawarau Gorge you've got the courage of Ned Kelly!”

Madeline: “I don’t think the car could have gone back over the Crown Range. The battery was low, the headlights were low and I had to walk in front part of the way so they could see where they were going.”

Madeline took this photograph of John Andrew with his Crossley. His gun and mud-splattered trousers and the quiet country road suggests he had been hunting, probably for ducks. The girl in the background is probably Rayena.

The Orlowski girls’ ability to work through obstacles reflects the self-confidence John Andrew instilled in them. Madeline has no memory of admonishment from her father for returning his car without brakes or lights, rather of how they worked together to get themselves and the vehicle back to him.

What she does remember is that she could not get to sleep that night. Like the others on the building site, the girls slept in tents. Whether it was the cold of the tent or a reaction to the events of the long day, she could not stop “shuddering” until Mavis took the rug that had been the dog’s bed and put it around her sister.

_______________

John Andrew was the sixth child and third son of Polish settlers in Otago, August and Franciska Orłowski. (It is not clear when the diacritical ł in their name was dropped, but it did not appear on the passenger list.) Their first child, Franz, died aged two aboard the palmerston during the 130-day voyage from Hamburg to Port Chalmers in 1872. By the time John Andrew was born in 1880 August had established himself in Waihola as a farmer and builder. August junior, born in 1878, took over the family farm. John Andrew left home and made his own way as a builder.

John Andrew moved his young family three times in North East Valley, Dunedin, as he constructed each house better than the previous one. His third, below, had an especially high roof in preparation for a second-storey ballroom for his girls.

Madeline, Rayena and Mavis outside 377 North Road, North East Valley, Dunedin. John Andrew used his homes to advertise the latest building trends and techniques, such as the angled corner, the square bay window and the intricate wrought-iron fencing. Apart from the front door and part of the fence removed for a driveway, the exterior features, even the gates and their iron frames, remain the same more than 100 years later.

John’s wife, Jane (née Robinson), was also the child of early Otago settlers. Jane’s Scottish mother, Madeline McKenzie (the beloved grandmother after whom Madeline was named), and English father, Robert, arrived separately in 1852 and had settled in Berwick, about 10 kilometres from where the Orlowski family lived in Waihola.

_______________

Madeline remembers her father telling her that her Polish grandparents, farmers living near Gdańsk, had been ordered out of their house by Prussian soldiers. The palmerson records their daughter, Maria, as a month old, so Franciszka would have either been heavily pregnant or had just given birth.

The family walked to Hamburg, and at one stage hid in a haystack to escape other soldiers. They survived mainly on “black bread.” August could well have been able to grab some savings before leaving his house but he was listed under New Zealand’s Assisted Immigration Scheme, which suggests he signed a promissory note to secure their place on the ship.

After France’s capitulation in the 1870–1 Franco-Prussian War, Prussian-occupied Poland became a volatile place for local Poles.

When August and his six siblings were born, between 1837 and 1852, Poland had already ceased being a geographical entity: A series of occupations by its neighbours culminated in 1795 with former Polish citizens being ruled by Prussian, Russian or Austro-Hungarian powers.

At first the foreign rule did not make much difference to the lives of serfs, previously at the mercy of Polish nobles and landlords, but as the occupation continued in north-west Poland, Prussian authorities started to germanise geographical names, then Polish Christian names in baptism certificates, then surnames in marriages, and started to conscript Polish men into the Prussian army, August among them. Knowing there were other Poles fighting for the French in 1870 exacerbated the ‘Prussian’ Poles’ reluctance to fight for their occupiers. To add to the insult, the soldiers who returned home found Polish schools closed and their language banned.

After Otto von Bismarck’s victory over France in 1871, he accelerated his drive towards forming a single German republic. At that time, emigration was at its height. Keen to relieve himself of those Poles who refused to be absorbed into the Germanic Lutheran way of life, Bismarck allowed them to leave.

There is little doubt that most of the Poles would have heard about the various opportunities available in Britain’s expanding colonies. Immigration agents spread the word, buoyed by the opportunity to earn ₤1 for each statute adult landed in New Zealand. News travelled fast among the small villages, where many people shared dwellings. If not also forced to leave, nearby villagers would have soon found out about the Prussian soldiers’ visit to August and Franciszka, and others like them.

_______________

August’s younger brother, Johann, his wife, Anna (née Maślak) and their 18-month-old daughter, another Maria, joined August and Franciska as Assisted Immigrants.

According to a report, dated 23 December 1872, by immigration officer Colin Allan and health officers Dr David O’Donoghue and Captain William Thomson, scarlatina and typhoid had broken out “principally among the children” but had not been fatal. The ship’s surgeon-superintendent stated that three adults and 10 infants had died from “other diseases” such as pneumonia and dysentery.1

Readers of the otago daily times on Saturday, 7 December 1872 read a slightly different story:

The long looked-for four-masted ship Palmerston, or, as she may be called, a shipintine, as she has her mizen polacca rigged, and her fourth mast as a barque, was sighted off the Ocean Beach on Thursday evening, from Hamburg, with the first batch of German [sic]2 immigrants under the Government auspices. The tug Geelong having towed the brigantine Swordfish, for Hobart Town, to sea early yesterday, perceived the vessel in the offing, took her in tow, and brought her up to an anchorage in the quarantine ground, a-head of the Christian M'Auslaud. Previous to the Palmerston entering the Heads, signals were made, “All well on board;” but on being communicated with by the Health Officers, Captain Thomson, Dr O'Donoghue, and Mr Monson, H.M.C., on arrival, it was found that a number of deaths from typhoid fever and scarlatina had occurred during the passage, and that there was one patient still suffering from scarlatina. The vessel was therefore placed in quarantine till further orders…3

Under the headline, Fever Ships at Port Chalmers, the newspaper reported on the same page that the palmerson was quarantined at the entrance to the harbour, and her passengers allowed on shore at the Spit.4 The report does not mention that the day the immigration officers visited the ship was the same one as the 228 statute adults eventually disembarked at Port Chalmers and brought into the Dunedin immigration barracks.

Two weeks after the palmerson landed, three immigration commissioners “minutely examined the ship and found her scrupulously clean.” They had “no hesitation” in declaring that “no emigrant ship entered this port better fitted in every respect for the conveyance of emigrants…” and that the “space allotted for purposes of airing and exercising was far in excess of that required by the Imperial Act.” They noted that the ship’s “expedient employed in flushing the water closets” was “worthy of imitation in [other] immigrant ships.”5

Five weeks after that, Mr Allan reported to the immigration office in Wellington that the palmerson’s single men and women were “easily disposed of” but “farmers and runholders are generally disinclined to employ men with a family and children” especially when they were “entirely ignorant of the English language.”6

Mr Allan said it had been “rather imprudent” to send out 100 families in one shipment. Only 28 had gained employment. He suggested the balance be “located together in a special settlement, as their plodding habits and fertility of resources would enable them to overcome difficulties; and their ambition being less extravagant than that of people from the Home country, their wants would be more easily supplied.”7

Rather than keep the unemployable immigrant families in the barracks at the government’s expense, Mr Allan arranged a contract for them to lay the Southern Trunk Railway through the Taieri valley, about 15 miles south of Dunedin. He deputised two from the immigrant group to join him and an interpreter to investigate the “nature of the work they were expected to perform” and, after the parties agreed on the terms, paid for “conveying them and their families in waggons” and bought timber to make frames for their tents.8

Mr Allan told his Wellington superiors that the “chiefly Danes, Norwegians and German-Poles… appeared to belong to the poorer classes, as was evident from the scantiness of their wardrobe.”

Despite his prejudicial and sweeping assessment of the palmerson immigrants, he seemed to want to help them make as good a start as possible. He reported that those working on the railway were soon “doing well and making good wages,” that he had heard “equally gratifying” reports from other employees, and asked the government to sell them land in the nearby Greytown township with the view of forming a “Scandinavian settlement.” The area was then known locally as “Scrogg’s Creek” after its surveyor, Samuel Scroggs. To stop confusion with both names (North Island also had a Greytown), Greytown, Otago, was renamed Allanton in 1895.

_______________

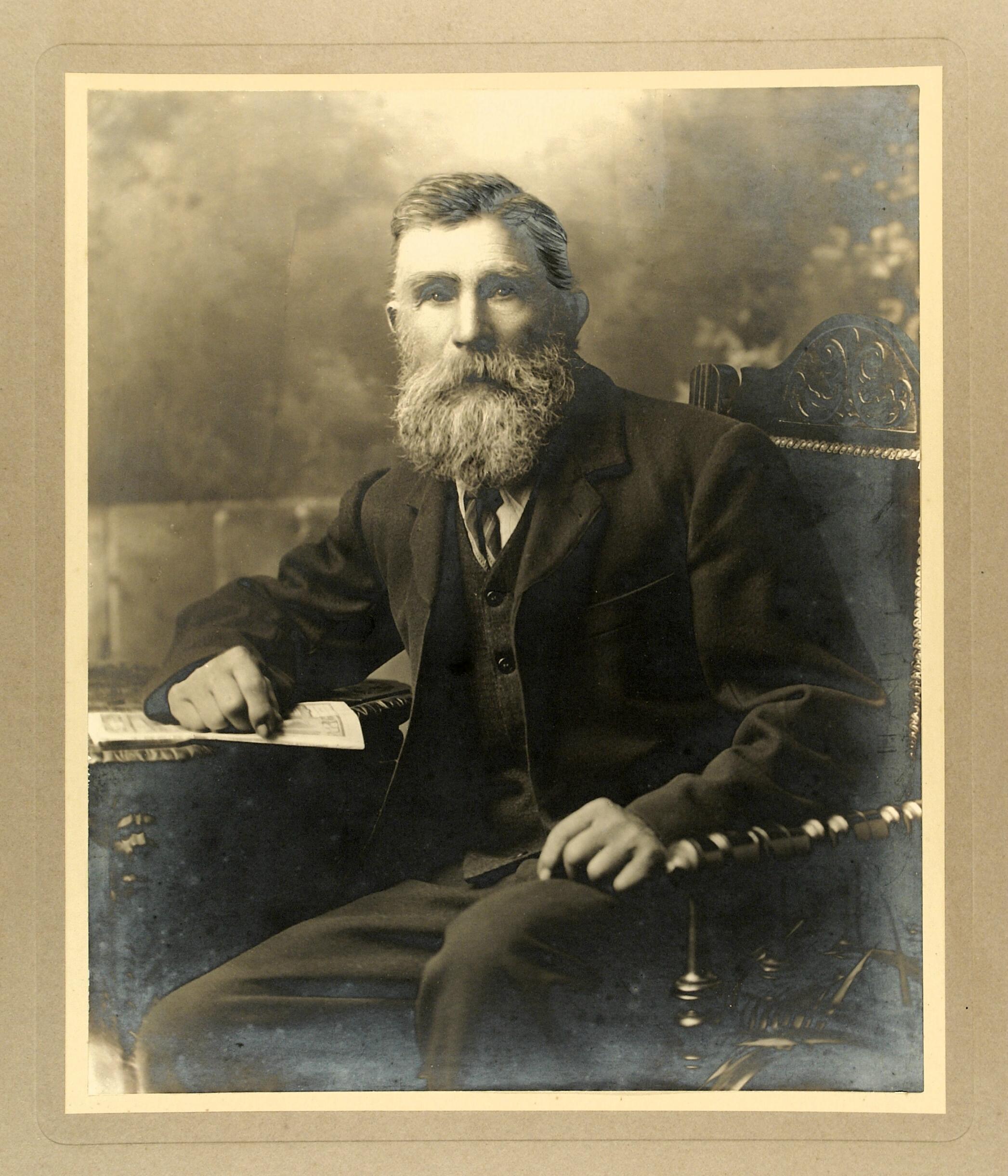

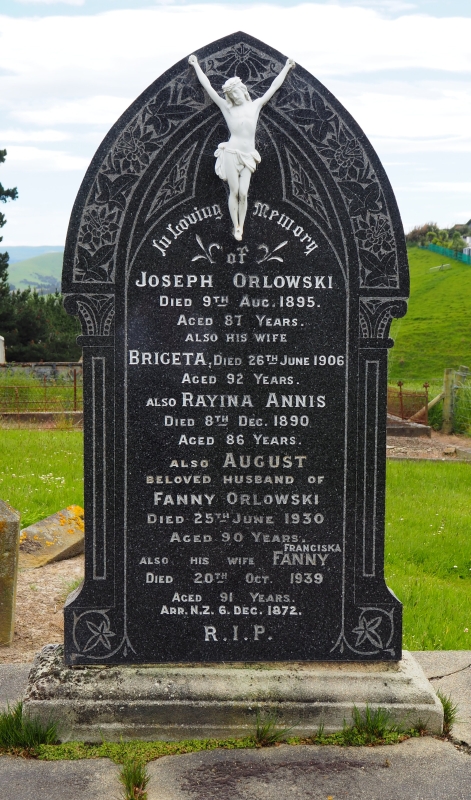

August, right, and Franciszka (née Anis) and Johann and his wife Anna instigated the immigration to New Zealand of their extended families.

According to Polish historian Paul Klemick, August and Johann’s parents, Joseph and Brigeta, had four children in Pszczółki (Anna Maria, August, Marianna, who died as a baby, and Johann) and three in neighbouring Skowarcz (Vincent Valentin, who died as a baby, Maria Rosalia, who died as a child and Joseph, born in 1852).9

Pszczółki and Skowarcz lie on the road between Tzcew in the south and Pruszcz Gdańsk in the north. Anna, August and Johann Orlowski were married in 1859, 1869 and 1870 respectively at the St. John Nepomuncen church in Godziszewo, about 15 kilometres west.10 Because none of their children had been born there, one may assume Godziszewo was one of the few places where a Catholic church still remained in Prussian-occupied Poland.

August and Franciszka’s first two children were born in Trzcińsk, south of Godziszewo. August’s sister Anna and husband Michael Wiśniewski’s first surviving child, another August, was also born in Trzcińsk and their last surviving children, Antoni and Bernard in Małe Turze, the same birthplace as Maria, Johann and his wife Anna’s first surviving child.11

In 1872, August and Johann left behind their parents, sister Anna and brother, Joseph. Franciszka Orłowska left behind her widowed mother, Rayina Rosalia Anis, her married sister, Marianna (Maria) Gręca, and a brother, Franz Anis.

The Wiśniewski family arrived in Dunedin on 6 August 1874 aboard the reichstag. Franz Anis was also aboard with his wife, Weronika, and their four children, Maria (4), Franz (3), Franciszka (2) and baby Anna, his mother ‘Regine’ Anis (then aged 63) and his sister, Marianna, with her husband Martin Gręca and Anna (11). The Gręca surname had by then been changed to Grenz and also appears as Grinz.

The Anis/Annis/Gręca/Grenz/Grinz family left for Hamburg from Małżewo, as did the Świtala family of eight, also listed on the reichstag. Franz Anis left with his family from Małe Turze, as did 17-year-old passenger Francisca Chilkowski. The Franz Anis and Martin Gręca families, with Franz’ mother, were listed as “Full Fare Paying Passengers” on the reichstag, the others as “Assisted Passengers.”

A year later, on 24 August 1875, Joseph (62) and Brigeta (55) Orłowski, landed in Port Napier. They had travelled on the same friedeburg that bought Poles to Lyttelton three years earlier. How the mature Polish-speaking couple found their way from the upper east of the North Island to their children in the lower South Island remains a mystery. They may have used the very railway that their sons helped build to link the previously isolated Taieri valley to Dunedin and the rest of New Zealand.

Brother Joseph was the last Orlowski to arrive in Waihola. The oamaru listed him as a 25-year-old labourer from Middlesex. The 1,306-ton vessel sailed from Glasgow on 24 October 1877 and berthed in Bluff on 13 January 1878 and Port Chalmers on 18 January.

_______________

Madeline recalls a family story of August buying land in Waihola, sight unseen, after an old Scottish woman living in Poland drew his and Franciszka’s attention to an advertisement offering the land for sale. That land, which looked so good on the map, in reality was a hill too steep for the farming it promised.

Although property ownership played a large part of the new colony’s lure, it is unclear whether August coincidentally bought land before he arrived in New Zealand in the exact area where immigration officer Allan steered them in 1872. However, by noon on 14 July 1873, August Orlowski had bought sections 10 and 11 of Block 21, Waihola township, for ₤3 each. On the same day Poles August Plewa and Johann Dysarch also bought two sections each and Paul Baungarat [sic] three.12

In 1878 the Waste Lands Board heard applications to buy land in Waihola from several of the palmerson Poles: Johan Halba, Franz Rekowski, Paul Baungardt, August Resewski, Johann Orlowski and Johann Dysarsh. (Names as spelt in the otago daily times’s newspaper article.)13

Although the early Polish settlers strove to buy land, it was not always easy:

August Orlowski appears in the government’s Return of the Freeholders of New Zealand, October 1882, as a Waihola carpenter owning three acres valued at ₤220. However, when he applied in 1886 to buy 50 acres of bush reserve in nearby Clarendon, he was turned down after a ranger named Hughan reported to the Land Board that “there was good firewood and land” and recommended that August’s application be declined.14

August’s great-granddaughter, Heather List: “And yet at the same time my other grandparents were getting land all over the place. They accumulated a lot during their time.”

The same freeholders list shows John Andrew’s future father-in-law, Robert Robinson, as a farmer in Berwick, with 2,247 acres in Taieri county, valued at ₤4,330. Besides the Berwick farm, Greenbank, he bought Granton farm and a sheep run extending 30 kilometres towards the Waipori river where for a time his youngest son, Christopher, joined Chinese diggers prospecting for gold. In 1882 Robert junior, also listed as a Berwick farmer, held land valued at ₤100.15

When August Orlowski discovered his land was too steep for productive farming, he turned to his profession in Prussian-partitioned Poland—carpentry—and was soon in demand for the many new buildings needed in the Taieri area, including a substantial woolshed and other out-buildings in Berwick for the Robinsons.

Madeline: “It’s still there, in good order.”

Heather: “The house is long-gone but the woolshed is still there. He didn’t build the house.”

The woolshed and out-buildings that August Orlowski senior built on the Greenbank farm in Maungatua Road, Berwick.

New settlers often built their first homes from material available on site. Johan Świtala, for instance, built a two-roomed sod cottage on the acre he bought in Greytown.16 He replaced the original thatch with a galvanized iron roof used to collect water. Fresh straw on the earth floor kept the home warm and dry during winter. The cottage outlived Johan, who died in 1913, and his widow Franciska when she moved later into a Dunedin retirement home.17

_______________

Immigration officer Allan may have presumed that the Poles would be happier living among themselves, and there is no doubt that until they learnt English, they would have found it hard to communicate with the predominantly British settlers.

By the time John Andrew was born, August had established himself as a builder, as had his brother, Johann, by then also known as John.

The Polish community in Waihola valued being able to practice their religion freely. After 20 years’ travelling to Milton or Allanton for Masses, marriages, christenings and funerals, they built their own church.

John Philipowski donated the land. August Orlowski helped the official builder, a Mr J Agnew from Balclutha, and kept the building in good repair. It became a place where the Poles would stop on their way past and say a prayer.

Once the old Poles died and the Catholic community in Waihola dispersed, their church was moved in 1948 to Broad Bay in Dunedin.

August’s early forays to the Resident Magistrate’s court show he had a clear idea of the value of his craftsmanship.

He took fellow palmerson passenger Franz Jankowski to court when he felt he had been under-paid. August had charged at 12s a day for building Mr Jankowski’s house, yet Mr Jankowski said they had agreed to 9s. That time August lost.18

August had a reputation for being “pretty tough” and John Andrew appreciated his maternal grandmother living with them.

Heather: “When he was a little boy and in trouble he would hide in his grandmother’s long skirts. He loved her very much. When Franciszka came to tell her eight-year-old son that his babcia had died, he said, “I know. She came to see me.”

Rayina Annis died in 1890, aged 86. She shares her grave in Waihola cemetery with her daughter, who became known as Fanny and who died in 1939, her son-in-law August, who died in 1930 and Joseph and Brigeta Orlowski, who died in 1895 and 1905 respectively.

_______________

August and Franciszka Orlowski’s nine children’s marriages reflect the assimilation of the early Polish settlers into New Zealand society. Only August junior married a Pole, Julia Dysarski, daughter of palmerston passengers Juliana and Johann Dysarski, and born on 2 July 1878. Her official name in birth records, Dysarch, is the same misspelling as the one recording her father’s land purchase the same year.

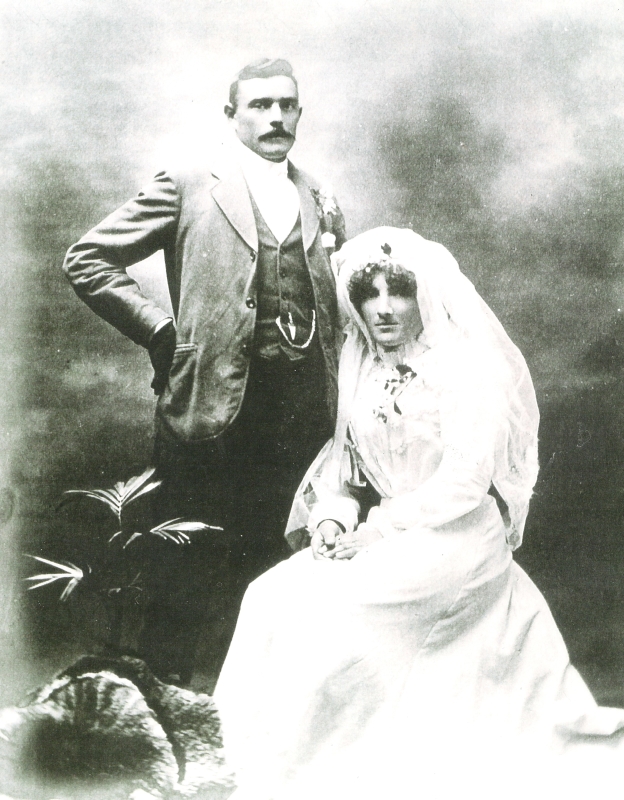

August and Franciszka’s great granddaughter, Clare Aston, found this Orlowski wedding photograph. If anyone can help with identification, please contact us through the home page.

August and Franciszka’s children:

- Maria, aged about five months when she landed in Port Chalmers with her parents. She became known as Mary, married Robert Anderson in 1893 and had four children.

- Anna, known as Annie, was the first Orlowski child born in New Zealand, in 1876. According to the family story, she married a Harry Clark and had three children.

- Martha, seen here, married Robert Storie in 1900 and had a daughter, Irene, who Madeline remembers as a “very pretty girl.”

- August junior was born the same year as his wife. He and Julia had six children. Julia died in childbirth on 2 July 1917 and Aunt Mary Anderson raised James Joseph, below. August remarried the following year to Elizabeth Hampstalh. When James enlisted in WW2, he was advised to change his surname to Anderson.

- Madeline’s father, John Andrew, was born on 3 October 1880.

- Bernard (Bertrum, Bert), born in 1882, changed his name, surname and religion, apparently after becoming annoyed with his father. According to the family story, the two were cutting down pine saplings when August told his son to take more care or he may lose his hand. Bert ignored the warning and when he accidentally cut off two fingers from his left hand, August laughed. His son left home, became Herbert Luskie, married Edith Wates in 1905 and had five children.

- James, born in 1884, married Hannah Moriarty in 1905. According to family story, they had 10 children.

- Thomas Alexander (Alex) was born in 1885. He apparently married and had two children but remains a family mystery.

- Michael Francis (Frank) was born in 1889 and married Ivy Yarrow in 1913. They had two children.

- Frances Clare (Fanny) married Robert Tisdall in 1910 and had nine children.

Another unknown Orlowski from Clare Aston’s collection. If anyone can help with identification, please contact us through the home page.

_______________

Madeline knew no prejudice resulting from her Polish name, although as a six-year-old she refused to go back to North East Valley School after children teased her.

“I started school there. I was always a well-dressed child. That may be why they picked on me. Coming home from school, about four or five boys and girls walked behind me singing, ‘Mad-e-lean, lean-chop, Mad-e-lean, lean-chop…’

“I didn’t like it. I didn’t know them. I refused to go to school. I started at the farm school in Clinton.”

Heather: “Grandad didn’t come across as Polish. He had no trace of an accent because he’d been born in New Zealand, and was just a normal fellow with an unusual surname. I don’t think he had any problems with prejudice at all.”

Madeline: “We didn’t have much to do with [the senior Orlowskis] because my father’s father preferred his oldest son. He managed to teach my father to be a builder but he had to make his way on his own.”

Franciszka Orlowska once borrowed a sovereign from John Andrew to put in the ballot for five plots of land. She won two but John Andrew saw none of the benefit. The family story is that Franciszka then gave John Andrew ₤100 to “look after,” which he refused to hand over to his father when August visited John Andrew’s Clinton farm.

_______________

John Andrew was living in Henley and working as a carpenter when he tweaked his age to join the two-year-old Boer War in South Africa. New Zealand’s Prime Minister Richard Seddon had committed the dominion’s support of the British Empire early and had already sent out seven contingents to quell the South African Republic in the Transvaal and its Orange Free State ally.

John Andrew joined the South Island Regiment’s G Squadron and gave his mother as his next of kin. He shipped out with the Eighth Contingent on the ss cornwall on 8 February 1902.19 Their commander, Brevet Colonel RH Davies, had already served in the First and Fourth Contingents.20

Madeline: “Wars weren’t like they are now. I think he went for a sense of adventure. He was fairly sympathetic with the Boers actually. He said he always shot over their heads.”

During the late stages of the war Boer leaders such as General Koos de la Rey “did not seem to be in the mood to negotiate,” said DOW Hall in his book the new zealanders in south africa 1899 to 1902.21 This despite the Afrikaners’ “increasing difficulties in maintaining themselves in a country stripped of stock or crops.”

The New Zealanders landed in Durban, went by train to Newcastle, northern Natal, and were sent to occupy some of the passes in the Drakensberg ranges:

Two squadrons of the South Island Regiment were sent to search the Klip River valley in the Orange Free State… occasional Boers were seen but not engaged. Some stock was bought in.

…the contingent marched by Charlestown to Volksrust in the eastern Transvaal. On 12 April, after passing through Potchefstroom, the second of the three trains carrying the South Island Regiment was run into by a goods train at Machavie. Sixteen members of the contingent were killed… eleven more were seriously injured.22

John Orlowski, soldier, pictured here on the far left. Standing behind him is Christopher Robinson, his future best-man and brother-in-law. The other men are unknown. The New Zealanders dressed more casually than the British in South Africa during the Boer War, in khaki with puttees and a slouch hat in the Australian style of the time.

By 1902 an estimated 20,000 armed Boers remained “in the field.” The drive to flush them out in the Klerksdorp area began on 7 May 1902. By 11 May 360 prisoners had been taken, some by the New Zealanders, who had also gathered 280 cattle, 200 sheep and a few horses. By 16 May they were following Colonel Davies towards the Transvaal border:

This march was interrupted on 20 May by orders that the New Zealanders were to go to Klerksdorp to meet Mr Seddon, who was then making a tour of South Africa while en route to England… it was still at Klerksdorp on 31 May 1902 when peace was signed.23

The family story says John Andrew picked up what he thought may be a diamond, a clear stone that could cut glass, but “was relieved of this back in New Zealand by a man who offered to have it tested.”

_______________

John Andrew Orlowski engineered this balanced draw-bridge over the river out of Lake Waipori around 1903. Judging from the proximity of the Robinson farm and amount of land his future father-in-law had in the area, Robert Robinson could well have commissioned it. The river ran into the Taieri Mouth so the bridge may have been constructed to accommodate river traffic.

A scarlet fever epidemic cemented Jane and John Andrew’s romance. Jane, by then in a long-term engagement, decided to help her younger sister, also a Madeline, when she and her two young sons caught the disease. Madeline’s husband, William McKegg, had left the family home in Taieri Mouth so he could continue running his general store and bakery.

Newspapers in late 1902 and 1903 regularly reported on the scarlet fever and the need to remain within infected sites until they were certified safe. “The penalty provided by law for such offences is heavy,” said the evening star on 31 January 1903. Three weeks later the otago daily times reported:

“Taieri Resident,” who has not sent his name, refers to a suspected case of scarlet fever at Momona, reported to the health officer at Dunedin by the chairman of the local school committee, the case being that of a child whose father is connected, with an important industry. “Taieri Resident” has no doubt that the heath officer gave the necessary instructions to the parents as to isolation, etc., but he urges that the father should not go backwards and forwards between his residence and the factory at which he is employed, and which deals with an article of food of daily consumption. He should send his complaint to the health officer.24

Heather: “Madeline’s husband took off, leaving his wife and children with scarlet fever. Jane moved in to help her sister and the two little boys, and caught it too. Enter the handsome hero, Jack, who moved in as well and nursed all of them… He was in love with Jane.”

John Andrew had years earlier joined his father on various building sites, such as the Robinson’s, and had become a close friend with Jane’s brother, Christopher. There is no doubt John Andrew and Jane knew each other socially by the time the “hero” stepped in to help.

His scarlet fever patients all recovered. Jane broke off her engagement and married John at a lavish function at the Robinson’s Berwick farm on 10 February 1904.

Jane née Robinson and John Andrew Orlowski on their wedding day. Jane’s bridesmaid Madeline, far left, was her older brother Robert’s daughter. John Andrew’s best man, far right, was Jane’s youngest brother, Christopher. Heather found 17 Madelines in the immediate family tree, named after their Robinson matriarch Madeline, née McKenzie.

Guests at the Orlowski-Robinson wedding feasted on a “wedding breakfast of turkey, chicken, ham etc served in a large marquee” at the Greenbank homestead in Berwick.

“My father said he would shoot himself if Jane didn’t marry him. He wouldn’t have, of course…”

Madeline doubts her father’s estrangement from his family resulted from his marriage to a non-Catholic non-Pole. August and Franciszka Orlowski attended the ceremony and festivities.

“I think his parents would have been very happy about his marriage because my mother was the daughter of a very well-to-do farmer.”

The young couple settled in North East Valley, Dunedin. The houses John Andrew built for his family—each a bit better than the one before—advertised his newest building techniques and trends. He became known as “Honest Jack.”

The notation at the back of this baby photograph suggests that Madeline McKenzie Orlowski was born in Frame Street, Dunedin.

Madeline’s earliest memory occurred soon after Rayena’s birth. By then they had moved to Queensbury Street, next door to Jane’s mother.

The Orlowski’s second home, 10 Queensbury Street, North East Valley, Dunedin, in 1960. Rayena was born in the room on left on 7 August 1909. Mavis and Gertrude were both born at the North Road property.

Heather: “Mum was standing on the veranda and her mother was nursing the baby inside and wanted mum to take a message to her grandmother. Mum didn’t go, and her mother called out through the open window, ‘Why didn’t you go with that message?’ and mum said, ‘Because I didn’t want to get wind like baby.’ It was a windy day.”

Madeline: “I was two years and three months old.”

_______________

Fortuitously for Madeline the after-school teasing coincided with her father meeting a Mr Peart, who had a 350-acre sheep farm in Clinton which he was keen to swap for the several unsold houses that John Andrew had accumulated by that time.

John Andrew loved being a farmer and his girls loved it too.

“We had a band of beautiful blue-gum trees right round the house. When the wind blew, you thought it was the sea making the noise.”

Years ago Madeline wrote a memoir about Clifton Park. She recalled the rustling of the leaves and waking in the mornings “to the song of a hundred birds. There was a high swing hanging from those tall trees… each year there was a wonderful children’s party when children arrived in buggies or horseback and a feast was spread in the billiard room where a cascade of cream roses fell from the ornate kerosene lamp hanging from the ceiling.”

Madeline wrote how she and her sisters loved to listen to their mother’s stories of her own childhood and her capable and hospitable Scottish mother, who “dressed with care” for the evening meals, kept “embroidered and starched and spotlessly clean drapes over the beds” and—in the absence of doctors—delivered babies and gave First Aid to neighbours.

“There was a macrocarpa hedge closer to the house. It was our playhouse. It had a little doorway to it. The trees were so close together, you could almost walk across the roof.

“We used to play housekeeping… I don’t know whether my mother ever knew that we used to light a little fire there, because that was terribly dangerous.”

Clifton Park, about five kilometres north of Clinton, taken from SH1 in 1992.

The homestead was not built by John Andrew and these people are not his family.

Madeline and Rayena started school in Clinton in February 1914.

“We were too young to be seriously affected by the shadow of World War I and the years we spent at Clifton Park were happy ones.”

John Andrew kept two cows. Jane refused to allow the girls to do any milking but they did help make butter. A washerwoman came once a week and boiled up the water in the copper, which stood in the wash-house, a shed separated from the main house. Modern washing machines then had a handle to agitate the load.

The “colourful characters” from Berwick still get Madeline animated.

“Waicher Mackay was always calling out to passers-by, ‘Wait-yer, wait-yer, what’s the news o’er west the day?’

“Another character, Dan Heenan, had a gadget built over his grave with a glass front and a suit of clothes in it, there for him to use when he returned. He was coming back. It was a box with a door. I’ve seen it. It was quite a good suit waiting for him.”

Daniel Heenan’s tomb in the West Taieri cemetery. Records describe him as a farmer who died on 9 December 1898, aged 59, with no next of kin. He does not share his his elaborate memorial.25

_______________

Madeline remembers Mavis risking her life to save their dog at a summer outing to Taieri Mouth. They walked to the island at low tide but waited too long to return. The strong current caught the dog and Mavis jumped after it.

“She was such a brave person. She was nurse aiding in a hospital when she was involved in an aeroplane accident. Doctor Blanc asked her to go with him to Alexandra.”

Heather: “They had to collect some serum because there was an infantile paralysis outbreak. The weather was bad and they had several messages, ‘Don’t come, don’t come.’ Then there was, ‘It’s all right, weather cleared,’ and they left. Only after they were in the air, there was another message, ‘No, weather’s worse than ever, don’t come.’ There were three of them because although Mavis and the doctor were taking flying lessons, they didn’t have their pilot’s licences.

“Mavis knew the countryside they were flying over—near the Lambhill Station at Hindon where Uncle Chris farmed—because she had holidays there. She knew when they turned into a blind valley that they would come to a sticky end, but she couldn’t make herself heard above the noise of the engine and the noise of the storm, and sure enough, the plane crashed.

“She was temporarily knocked out and her foot was caught. When she regained consciousness a few moments later she saw that both the pilot and the doctor had stepped over her and were out of the door.

“‘The age of chivalry is past,’ she said as she picked up the serum and got herself out of the plane.”

Mavis’s farm experience showed a few years later when the family was again living in Dunedin.

Heather: “In those days the drovers used to drive the sheep or cattle through town to the freezing works.

“Mavis happened to be in town when some city dogs had gone yapping at these cattle. Five or six broke away from the herd and were hurtling down a street. Mavis stood in front of them and yelled, ‘SHUT UP, THE BLOODY LOT OF YOU!’ and the cattle came to a shuddering halt. That was typical of Mavis.

“I can’t be sure of her exact words. My father told the story with much gusto and minimal clarity.”

Seven years of idyllic life on the Clinton farm ended for the girls when Madeline fell from the gig taking them to school.

Heather: “It was driven by the farm hand, Bob Robinson, a cousin of mum’s.

“The girls all sat in a row on the seat, but the seat overhung the wheels on either side and they think perhaps the horse stumbled. It had stumbled before. In fact, mum had fallen out of the gig before. It is possible that the wheel might have gone over her face…”

Madeline: “Where you put your feet was very narrow, so it was quite easy to fall under the wheel…”

Heather: “They called the doctor from Balclutha and he came and at this stage she had a tooth hanging down…”

Madeline: “On a bit of skin…”

Heather: “He cut the tooth off, bandaged her face and ordered her to be ‘raced’ to Dunedin by the fastest possible means, which was of course the afternoon train. It was the only time she saw her dad cry. She tried to comfort him.”

The hansom cab that took Madeline to the private hospital on Royal Terrace greatly impressed her.

Madeline: “I had two operations, one six hours and seven hours the next night. The surgeon who did them had war experience, Baron was his name.”

Madeline’s cousin, Amos McKegg (whose father or grandfather commissioned the Wanaka house), attended the Dunedin Dental School at the time and was invited to watch the procedures.

Heather: “They did such a good job that she had no scarring.”

That accident became the reason behind the family’s return to Dunedin, although it may not have been the only one: The need and lack of a hospital in south Otago had been prominent in the newspapers in early 1920 and Madeline had not been the only one to fall out of a gig. This appeared in the bruce herald on 10 April 1920:

Whilst driving a horse attached to a gig down a steep hill near Clinton the other day two ladies met with an accident that had painful results for one of them. The ladies—Mrs Orlowski and Mrs Anderson (a visitor from Dunedin)—were precipitated out of the gig on account of the horse falling, Mrs Anderson sustaining a badly fractured wrist. Mrs Orlowski escaped injury.26

After Madeline’s accident Jane Orlowski rented a house in Clinton so that the girls did not have to travel to school by gig. She took them home to the farm at the weekends.

Heather: “Grandad wasn’t impressed with that arrangement so they moved back to Dunedin.”

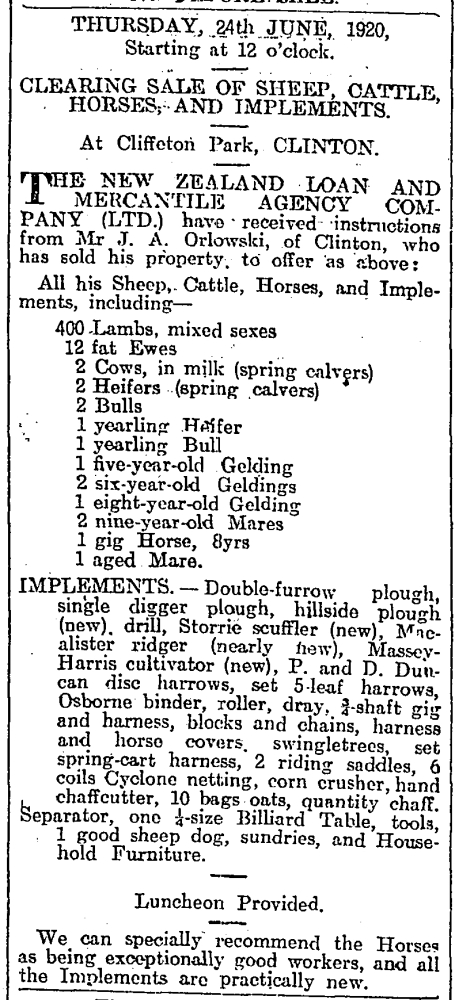

John Andrew’s advertisement in the otago daily times:27 Madeline remembers the gig horse was named Billy.

This time John and Jane chose Dunedin’s seaside suburb, St Clair. John Andrew built the family’s final house at 173 Victoria Road. The address may have had something to do with the Forbury Park Raceway about 500 metres away.

The December after John Andrew advertised his sheep, cattle, horses and implements, he made the sporting pages of the mataura ensign:

Cliffeton Chimes, who won the Second Amateur Handicap at Forbury on Saturday, was bred, broken in, trained and ridden by his owner, Mr J. A. Orlowski, Clinton. He is by Four Chimes from a King Harold mare. The dam was previously owned by Mr J. M. Peart, Waimumu, who sold a farm at Clinton with some stock, including the King Harold mare, which was then in foal to Four Chimes. A lot of money came to Clinton supporters as a result of Cliffeton Chimes’ success.28

The Mr JM Peart who sold a farm at Clinton “with some stock” may well have been the same Mr Peart who exchanged his farm for John Andrew’s Dunedin houses.

John Andrew loved his horses, fishing and shooting. He regularly made trotting news, in June 1933 sharing the copy with indefatigable Mavis:

At a recent meeting of the Forbury Park Trotting Club an amateur license to train only was granted to Mavis Ethel Orlowski, her father John Andrew being granted a similar license to train, drive and ride. This must be the first occasion on which a lady enthusiast has been approved of a privilege to train at Forbury Park and the incident has aroused a good deal of interest. The person in question has always been fond of horses and is able to ride as well. Her father has long been connected with the light-harness horse, one of his own possessions being Spring Note who raced at the pacing gait and finished second at Forbury Park a few years back. At present a rising three-year-old by Adioo Guy is one of Mr Orlowski's claiming most attention. Kolmar is now also in the stable.29

The “person in question,” Mavis Orlowski. Her gleaming riding boots and groomed horse suggest she may have been preparing for an event. The location could have been taken her Uncle Chris’s farm near Hindon, which she visited often, or the Lowe farm near Ashburton.

Back in Dunedin John Andrew, Champion Shot for seven years before he moved to the Clinton farm, became a life member of the Dunedin Gun Club. He continued competing and was in the team that won the prestigious Bodkin Shield in 1949.

Madeline finished her Standard Six at St Clair School, and from 1922 to 1925 attended Archerfield School for girls, created “For the Education of Young Ladies” by Sarah Nisbet after her husband, the Rev Dr Thomas Nisbet died.30 The curriculum included First Aid, nursing, history of art, current events and swimming and Madeline loved it. She finished her schooling at Brown’s Secretarial College.

Rayena, the family’s thespian, went to Otago Girls High School. At 16, she entered the elocution division of the Dunedin Competitions “Recitation, 12 and under 17 years—Own selection, not humorous” and lost the first prize by only three points.31

Madeline: “Rayena won the Shakespeare prize and was a devotee of Shakespeare for the rest of her life, taking dramatic parts such as Lady Macbeth and Joan of Arc. She had a great love of literature and was widely read, deploring the fact that I was not similarly equipped.”

During her four years at Otago University, Rayena took top prize in English, sharing the first year with future war correspondent Geoffrey Cox. In 1929 Rayena won the institution’s Gilray Memorial Prize for English. She also studied French at the university and loved art, taking up painting in her retirement.

“She always took her turn as voluntary helper at the Art Gallery and was very pleased when one of her paintings was selected for display and got a good write-up.”

Madeline remembers that Rayena paid for her to have singing lessons.

Heather: “Before the second term started, the teacher phoned and asked Madeline if she had been practicing. She hadn't. Did she have the courage to sing in public? She didn’t. ‘Well, don’t bother to come back!’ he said. She didn’t.”

Gertrude had a flair for dancing. At nine she entered and won the Dunedin Competition’s dancing section “Dance Duo, other than dramatic, under 12” with her partner Bettie Collie.

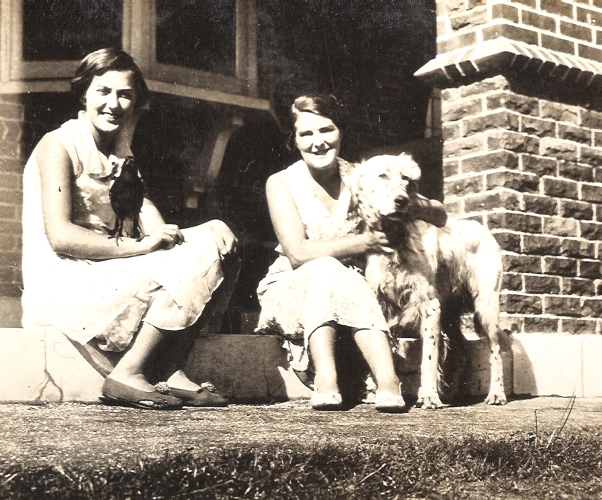

Gertrude in the Victoria Road back garden with Kelvin Grouse the family dog.

On the front steps of the Victoria Road house, Mavis holds Shot, the dog she rescued at Taieri Mouth, while Maggie the magpie rests on Gertrude’s arm.

Gertrude, Madeline and Rayena at a party held at the Hinds homestead of John Andrew’s friend, Mr Lowe. Mavis, known as a wonderfully efficient cook, was probably in the kitchen.

While the girls settled into school life in Dunedin John Andrew re-established his building business.

Heather: “He built houses all through the Depression and kept his men in employment when so many were unemployed. He used to claim he built most of St Clair.”

While doing a door-to-door survey in North Road about 30 years ago, Heather mentioned to one owner that she thought his house was one of the ones her grandfather had built and lived in.

“He said, ‘Yes, that’s right,’ and he took me to the back. The stables were still there… and you could still read, very flaky paint, you could still read ‘JA Orlowski’ on the stable wall.

“This man said he could remember watching the building of the house when he was a small boy living next door. On one occasion the workers had left their teacups on the unvarnished windowsill, leaving rings. With one swipe of his arm, John Andrew sent all the cups out into the yard.

“Another time he was berating a labourer for not using four hits per nail when fixing floorboards. You had to get into a rhythm: Three was too few—you'd bruise the wood—and five showed you didn't know how to use a hammer.”

Mavis told Heather she had been puzzled about the time her father sported a black thumb he refused to explain. A former apprentice told Mavis that John Andrew had objected to the wood being bruised when nailing a mantelpiece.

“THIS is what you hit!” said John Andrew putting his thumb on the nail.

_______________

The Victoria Road house backed onto the St Clair sandhills. Madeline celebrated living so close to the sea by swimming every morning.

“I did it for a year. I heard someone at St Kilda had done it so I did the same. In winter I’d go out and there’d be frost on the ground. I got tonsillitis so I didn’t do it again.”

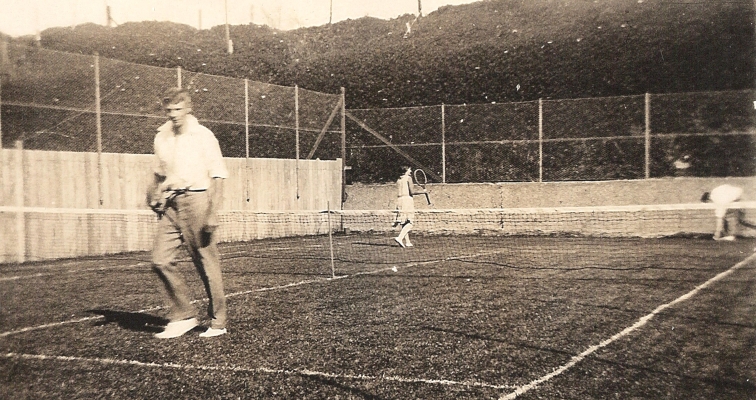

John Andrew tempered his ballroom idea but did set down what proved to be a well-used tennis court in the back garden.

Heather: “Jane broke off her engagement with Don Sinclair but it didn’t end the friendship. His son, also Don, became very friendly with the four girls. He and many young people would come and play tennis, one of them Jack Lovelock, who won the gold medal at the Berlin Olympics. He was very sporty and they knew he was in training, but of course they didn’t know then that he was going to win the gold medal.”

At the Victoria Road tennis court, from left: John Lovelock, Madeline, Rayena, a neighbour, Gertrude and Don Sinclair junior.

The Orlowski tennis court and St Clair sandhills with John Lovelock in the foreground.

_______________

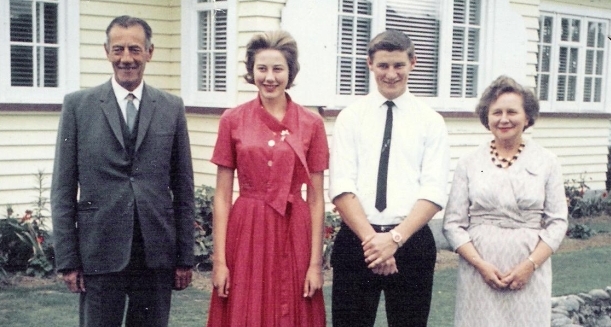

The sisters married in reverse order of their births. Gertrude married James Macassey (Pat) in 1935 and lived on the farm Pat’s father bought him and his brother in Dacre, Southland. A year later their son John was born at the Victoria Road house “besides the sand dunes and close to the sea, which was one of the first sounds I heard.”

John: “When my mother returned with me to the Dacre farm, one of her sisters-in-law and her mother-in-law came to stay. Rather than assist my mother they treated her like a servant so my mother returned to 173 Victoria Road and refused to return until the sister-in-law and mother-in-law departed.”

Pat left New Zealand in 1940 with the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force and Gertrude again moved back to Dunedin, this time also with baby Patricia, born in Invercargill. Mavis had by then married Douglas May and lived a few houses away from her parents. Madeline and Harry lived opposite John Andrew and Jane and John Macassey, first grandchild, basked in the adult attention of his affectionate and loving extended family.

Gertrude played modern and classical piano, introduced her son to the cinema and kept the lightest of reins on John as he explored the beach and cliffs and created adventures with his friends.

Pat survived the war. John returned to the farm with his mother, sister and a single shot .22 rifle that his Aunt Mavis gave him to hunt the thousands of rabbits on the farm. Gertrude taught him “safe use” of a firearm. For his 10th birthday John was allowed to go hunting alone.

“For several years I made more than the adult minimum wage from selling rabbit skins.”

_______________

Like her mother, Madeline had a lengthy first engagement.

Heather: “It was the depression and she had a job as a stenographer and he was always struggling and went to Christchurch thinking prospects might be better but they weren’t and the engagement eventually fizzled out.

“By this stage Rayena had married Don McRobie and moved to Auckland so mum went up to keep her company.”

John Andrew went to Auckland in the summer of 1935–36 to check on the welfare of his elder daughters and took Madeline to Rotorua. Here she is with her father, centre, probably at the hot pools in Whakarewarewa.

Sisters in Auckland: Madeline with Rayena and her husband Don McRobie, whom she married on 10 December 1940. Dressed in uniform are, far left, Rev Alec McDowell, who had been Madeline’s minister in Dunedin, and Dick Hood.

“Mum was staying at a boarding house called The Mansions. Boarding houses were quite the thing at the time. All the young people stayed in these boarding houses and dad’s version of the story is that she and a friend, one of the other female residents, were going up the stairs and dad was coming down the stairs and remarked to his companion, ‘I’ll have the one with the blue eyes and the golden hair.’

“I’ve been going through photos and I there are quite a few ball photos and quite a few different partners. I gather that the competition was quite keen at the time… Eventually she got fed up went back home and talked it over with her mother saying, ‘I’ve got these young men courting me…’ In the end, she decided that she preferred Harry, who had come to Dunedin with the hope of getting engaged.”

Madeline’s white fur jacket from Dunedin became useful for the many balls she attended while living at The Mansions. With her here are Flo and George Bonny standing at the back, her room-mate Mary Wakelin and Jack Martin.

“It’s amazing that mum had several young men courting her because it was wartime and so many of the young men were overseas. Dad didn’t go because he had varicose veins in his legs although the veins didn’t affect him at all. He competed in marathons and was a red-hot tramper.

“Later they did call him up because he let them know that he had done Stage One German for his Bachelor of Commerce degree. They sent him to Auckland for training but his employers phoned and said they needed him. By then he was married and working for the Transport Department re-organising milk collections.

“So mum went back to Auckland to get married and because it was wartime the only people there were mum’s sister, and dad’s best friend—the witnesses—Ray’s husband and a woman that mum had sat next to on the train. No parents. They hadn’t met brothers or sisters or anything like that.”

Madeline McKenzie Orlowski married Henry Anderson on 6 September 1941. They lived in Auckland for a few months but Dunedin beckoned and the young couple settled opposite John and Jane.

Madeline with Brian Anderson, born on 26 September 1943, on the occasion of his baptism.

Heather was two and Brian five when the family moved to Upper Hutt in 1947. Jane had her first stroke after Brian was killed in a bicycle accident, aged seven, on the road outside the family home. In those days it was Main Road. It has since changed to Fergusson Drive.

After Brian’s death, Madeline and Harry fostered four-year-old Graeme Wayne O’Connor. His mother never allowed him to be adopted but he was very much a member of the family. He died, aged 20, when he fell asleep at the wheel of his car.

Harry, Heather, Graeme and Madeline outside their home in Upper Hutt circa 1965.

After Jane’s stroke, Mavis, who still lived nearby, cooked midday dinner for her parents and husband Doug, who worked at Dalgety’s in Dunedin. Madeline and Rayena went down twice a year to help. Jane lived for another 10 years and died on 28 June 1961, aged 89. Gertrude died suddenly a year later.

Heather: “Grandad grew gladioli and carnations commercially in that very large back garden and had a glass house and a hen house with two or three compartments. He collected kelp from the beach and put it in with the hens. I think that was so that they could eat the bugs. Later he buried the kelp in trenches in the garden. He was pretty well set up. He kept himself and a lot of their friends in vegetables.

“He replaced the tennis court with a vast workshop arrangement. There were a couple of caravans inside the workshop, fully set up. We used to stay there at Christmastime because all the family descended there and so the kids were put out in the caravans. We thought it was fantastic of course.

“One May holidays Grandad offered me a job. I was to sit with him in a brick shed and peel gladioli corms, removing last year's shrivelled corm from underneath, and being careful not to remove the growing points when peeling the skins back. Mum and Aunty Mavis thought that this was no way to treat me, but I was happy enough to do this every day for a week for a shilling an hour.

“Grandad used to make jams and jellies out of the raspberries and black and red currants. When he moved in with us in Upper Hutt he continued to do this with fruit growing in our garden. Our garden was never better than while he was living with us. The soil was good but he claimed that between May and September there were only six days that it didn't rain.

“Dancing with him at social functions I noticed how soft his hands were, compared to the rough hands of one of Mum's friends, also a keen gardener.

“Grandad built their first fridge, and it worked quite well. When he moved up here after grandma died the fridge came too. He might have bought the mechanisms but it was made of wood—nearly everything he made was wood. That fridge lasted for years.”

The Crossley proved almost as indestructible. John Andrew converted it into a truck and took it to the Dacre farm in the 1950s where it lived out its life in happy usefulness.

The Victoria Road house decorated for a Royal visit in January 1954. The red, white and blue gladioli in John Andrew’s front garden caught the eye of Prince Philip, who waved to the people involved in the tableau as he and Queen Elizabeth passed.

John Andrew had been a staunch supporter of the Royal Family since he met then Princess Mary of Teck and her husband, the future King George V, the year after he returned from the Boer War.

On a visit to New Zealand the Royal couple had been taken on a trip down the Taieri river in Henley to a popular picnic spot overlooked by a much-photographed cliff, Governor’s Chimney (Te mai kau mai).32 Amos McKegg, father of the William McKegg who left Jane’s sister Madeline and their children with scarlet fever, owned the Whitehouse Hotel in Henley and several small steamers used for excursion parties along the Taieri. William skippered the steamer, so one may assume that John Andrew had been crewing for him.

The family story: “On arrival at the picnic spot, the Princess said to John, ‘Give me your arm young man. I want to climb up to the Governor’s Chimney.’” And so he escorted her.

Apparently William was so affronted that he refused to allow John Andrew back in the boat.

_______________

“I remember Grandad being genial and gentle. He was hard of hearing when he lived with us. Every morning he would listen to the news at high volume and then make loud angry comments about what fools the government (or whoever) were. He loved a good argument, but sometimes overstepped the mark, and I suspected that the occasional black eye that he sported was due to some episode at the bowling club rather than the medical explanations he was giving.”

John Andrew, second from right, with St Clair bowling colleagues around 1940. The four bars on his Orphans Club badge indicate 40 years’ membership.

“He was about 10 years younger than Grandma. It was obvious to me as a child how devoted he was to her. When she died, he said that she had had to be in this world for 10 years before him, so he should live for another 10 years without her. And that's what he did.”

John Andrew Orlowski continued playing indoor and outdoor bowls and until shortly before his death packed his car for the annual duck-shooting season and joined his friends, the Lowes, at their farm, Clarendon, at Hinds near Ashburton.

The family story: “He always returned with a bag of ducks and some walnuts gathered from the laden trees there. On the last occasion he gave his gun to young Billy Lowe who used to help him build the mai-mais and accompany him during the cold early hours of shooting.”

A few weeks before he died on 2 September 1971, John Andrew flew down to Dunedin to see his solicitor and spend some time with Mavis and Doug at their home in Karitane. He died there and is buried with Jane in Taieri West Cemetery. Mavis died in 1989 and Rayena in 2006.

John Andrew Orlowski reserved his forceful personality to those outside his immediate family. His consideration and compassion to his wife, his daughters and their families knew no bounds.

John Andrew with his daughter Rayena McRobie, his granddaughter Janice Goode and his great-grandson Robert Goode.

Madeline cajoled her father out of his sickbed to be part of another four-generation photograph. John Andrew, suffering from bronchitis, had “turned his head to the wall” and announced he was dying but Madeline knew he loved having his photograph taken. The sunny day and visiting granddaughter and great-grandson Heather and Daniel List did the trick: John Andrew “recovered quickly.”

Polish Ambassador to New Zealand Zbigniew Gniatkowski was one of Madeline's many visitors who helped Madeline celebrate her 110th birthday on 4 May 2017.

Madeline’s predominant memory of her father is the love he lavished on her and her sisters and his continual involvement in their lives.

“When you love a person, you know how to help them.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2017

Updated May 2018.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

PHOTOGRAPHS: Unless otherwise specified, all photographs come from the Orlowski collections held by Madeline Anderson, Heather List and Clare Aston. The tomb photograph is from Dunedin City Council. The former Waihola church and Orlowski headstone is by Barbara Scrivens, taken during a trip to Otago, for which the Polish embassy in Wellington contributed to travel costs. The studio photograph of August Orlowski senior comes from the website Poles Down South, cited below. The final photograph is from the Polish Embassy in Wellington.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1873 Session I, D-01, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND. MEMORANDA TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, page 36, Enclosure no. 41.

- 2 - The ODT writer of this article seems to have made the assumption that because the Palmerston arrived from Hamburg, the passengers were German. In fact they were mostly Scandinavian and, like the Orlowskis, Poles from Prussian-occupied Poland.

- 3 - Otago Daily Times, 7 December 1872, page 2, SHIPPING NEWS, Papers Past, through

the National Library of New Zealand,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT18721207.2.6 - 4 - Otago Daily Times, 7 December 1872, page 2, FEVER SHIPS AT PORT CHALMERS, Papers

Past, through the National Library of New Zealand and the Creative Commons New Zealand BY-NC-SA licence,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT18721207.2.12 - 5 - Ibid.

- 6 - AJHR, 1873 Session I, D-01, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND. MEMORANDA TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, page 49, enclosure 1, no. 52.

- 7 - Ibid.

- 8 - Ibid.

- 9 - From Poles Down South, the website of the Polish Heritage Trust of Otago and Southland,

https://polesdownsouth.wordpress.com/in-new-zealand/early-polish-settlers/annis-family/l-o/orlowski-family/ - 10 - Ibid.

- 11 - Ibid.

- 12 - Bruce Herald, page 4, 15 July 1873, Advertisements Column 6,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/BH18730715.2.8.6 - 13 - Otago Daily Times, page 3, 8 August 1878, WASTE LANDS BOARD, Papers Past, through

the National Library of New Zealand and the Creative Commons New Zealand BY-NC-SA licence,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT18780808.2.21 - 14 - Bruce Herald, page 2, 18 June 1886. Nemo me impune lacesset. TOKOMAIRIRO, Papers

Past, through the National Library of New Zealand,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/BH18860618.2.6 - 15 - A Return of Freeholders of New Zealand, October 1882, page 36 of section “R.” A CD of the

return is available through the New Zealand Society of Genealogists,

https://www.genealogy.org.nz/ - 16 - A Return of Freeholders of New Zealand, October 1882, page 101 of section “S.” A CD of the

return is available through the New Zealand Society of Genealogists,

https://www.genealogy.org.nz/ - 17 - From Poles Down South, the website of the Polish Heritage Trust of Otago and Southland,

https://polesdownsouth.wordpress.com/in-new-zealand/early-polish-settlers/annis-family/r-s/switala-family/ - 18 - Bruce Herald, page 3, 25 July 1879, RESIDENT MAGISTRATE'S COURT, AUGUST ORLASKI V FRANK

JANKOWSKI, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/BH18790725.2.11 - 19 - Ministry for Culture and Heritage, ‘john andrew orlowski,’ updated 8-Oct-2008.

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/soldier/john-andrew-orlowski - 20 - Hall, DOW, The New Zealand in South Africa 1899 to 1902. War History branch, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 1949. This and the following quotations about the Boer War from chapter 11, pages 72–75.

- 21 - Ibid.

- 22 - Ibid.

- 23 - Ibid.

- 24 - Otago Daily Times, 21 February 1903, page 8, CORRESPONDENCE CONDENSED, Papers

Past, through the National Library of New Zealand and the Creative Commons New Zealand BY-NC-SA licence,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19030221.2.89 - 25 - Photograph supplied to the Dunedin City Council by the Cemeteries Trust, Dunedin branch,

http://www.dunedin.govt.nz/facilities/cemeteries/cemeteries_search?recordid=56365&type=Burial

Other Dunedin cemetery searches available through

http://www.dunedin.govt.nz/facilities/cemeteries/cemeteries_search - 26 - Bruce Herald, 10 April 1920, page 4, CLUTHA NEWS ITEMS, Papers Past,

through the National Library of New Zealand,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/BH19190410.2.10 - 27 - Otago Daily Times, 22 June 1920, page 10, Advertisements column 2, Papers Past, through the

National Library of New Zealand, and the Creative Commons New Zealand BY-NC-SA licence,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19200622.2.85.2 - 28 - Mataura Ensign, 7 December 1920, page 7, SPORTING NOTES, Papers Past,

through the National Library of New Zealand. This newspaper digitised in partnership with the Gore District Historical

Society.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ME19201207.2.40 - 29 - Alexandra Herand and Central Otago Gazette, 28 June 1933, page 3, SPORTING, NOTES FROM

THE TROTTING SPHERE, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand. This newspaper digitised in

partnership with the Central Lakes Trust and used through the Creative Commons New Zealand BY-NC-SA licence,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AHCOG19330628.2.8 - 30 - https://www.ajswriting.com.au/archerfield

- 31 - Otago Daily Times, 28 September 1925, page 8, DUNEDIN COMPETITIONS, Papers

Past, through the National Library of New Zealand, and the Creative Commons New Zealand BY-NC-SA licence,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19250928.2.67 - 32 - For more about Maori lore in South Otago and Governor’s Chimney, NZETC, New Zealand Electronic Text

Collection, through the Victoria University in Wellington,

nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-TayLore-t1-body1-d21.html