POLISH ANCHORS 1872-1876

The first large groups of Polish settlers to New Zealand arrived between 1872 and 1876 as part of the new colony’s assisted immigration scheme. Their work on infrastructure and the land helped shape colonial New Zealand. By the 1880s, their number grew to nearly 1,400.

Three ships—the friedeburg, the palmerston and the reichstag—carried the bulk of the Poles from Hamburg to Christchurch and Dunedin between 1872 and 1874.

The friedeburg made a second voyage to New Zealand in 1875, docking in Napier. The fritz reuter, on its first voyage to New Zealand, arrived the same year, at the same port. Together, they carried fewer than 20 Polish families. By then Wellington was the preferred place to process new immigrants.

The humboldt and the lammershagen carried Poles to Wellington in 1875. The shakespeare and terpsichore followed in early 1876. The fritz reuter made a second passage to New Zealand, and arrived in August 1876. Its passengers were not allowed to disembark—the colony had ceased “foreign” immigration from continental Europe. Despite this, Poles continued to join their families in New Zealand, but travelled through London or Liverpool.

FAITH IN A SAFE ANCHORAGE

by Barbara Scrivens

Conscription into the Prussian Army was Albert Watemburg’s breaking point. The Pole cut off his trigger finger to ensure he did not kill other Poles he knew were fighting on the French side against the Prussians in the 1870–1871 Siege of Paris.

Poland had been under Prussian rule for 45 years by the time Albert was born in Rytel, part of the Czersk parish in the Kaszubian region of Prussian-partitioned Polish Pomerania. Between 1772 and 1795 the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s neighbours, Russia, Prussia, and Austro-Hungary, dismantled their shared enemy and divided her land. Geographically, Poland did not exist, but her citizens were tougher to subdue and remained staunchly Polish at heart.1

On the sandy, terminal moraine soils of a long-departed glacier, Rytel’s inhabitants relied on planting, maintaining, and milling mainly pine from the nearby Tuchola forest (Bory Tucholskie).

At first, the Prussians imposed their culture subtly but persistently, but by the time that Albert was born in 1840, his Polish name, Wojciech Watembach, stood no chance of being recognised by Prussian civil registers, no matter what a Polish priest may have uttered at his baptism.

Albert’s grandson, Ray Watembach, president of the Polish Genealogical Society of New Zealand: “My [maternal] grandmother should have been ‘Marysia’ [Neustrowska] but she was registered as ‘Mariane.’

“The Prussians found some of the ethnic Polish surnames a bit difficult to change, but the short ones like ‘Haftka’ became ‘Haftke.’ I found one set of Haftke baptismal records with the spelling ‘Haftkowski,’ which tells me that when the Germans tried germanising the name ‘Haftka’ to ‘Haftke,’ the family tried to protect themselves by connecting to Polish nobility who at that time were still not under pressure to change their names. The suffix ‘ski’ was usually attached to a noble estate, so the serfs started using ‘ski’ to indicate that the Germans shouldn’t touch them.

“When they returned home a year later they found the Polish language had been officially exterminated by an act of parliament…”

“By 1863, after the Polish Uprising, that protection disappeared, and conscription of Polish men into Prussian army units started. There was a Prussian military base in Starogard, in the middle of the Kaszubian territory, as well as one in Gdańsk. In 1870, the conscripted Polish men became involved in the Franco-Prussian war in which the Siege of Paris was the last battle that France lost. When they returned home a year later, they found the Polish language had been officially exterminated by an act of parliament, all Polish schools closed, and priests jailed or deported.”

Albert left for the Franco-Prussian War as a 30-year-old struggling to retain his Polishness in a place that held little hope for the future of his young family. He had married Katarzyna Roda in Rytel in 1865, and they had two children, Józef, three, and Marianna, a year old.

He returned at the height of Otto von Bismarck’s influence as Minister President of Prussia. In 1871, Rytel and its surrounds became part of the German Empire. Along with a worsening situation for Poles as a whole, Albert’s less than patriotic Prussian war record made him and his family even more of a target than some of his other Polish neighbours.

Speaking, reading, and even being in possession of Polish documentation of any sort had long been illegal, but then German soldiers began to roam the villages and search Polish houses for anything written in Polish, or associated with Catholicism. Some Poles lowered their lintels to force those soldiers to unknowingly bow their heads to the hidden crucifixes inside their front doors.

_______________

Stories extolling the virtues of a new colony in New Zealand caught Albert’s attention.

Positive descriptions of the new colony came from German agents employed by the New Zealand government to find labourers to build much-needed roads, railways, and bridges under the Colonial Treasurer Julius Vogel’s 1870 Immigration and Public Works Act. Emigration from the Prussian empire had already increased under Bismarck, and New Zealand was not the only colony vying for immigrants: America, Canada, and Australia offered attractive incentives through agents of varying degrees of honesty.

The New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863 had already given then-Governor Sir George Bowen the funding to create “special settlements,” and the ability to offer settlers the opportunity to buy any land previously ‘acquired’2 by the new colony.

On 5 July 1871, under the regulations for the introduction of assisted immigrants into the province of canterbury, New Zealand’s Agent-General in London, Dr Isaac Featherston, received instructions to invite “any person residing in Europe who had the necessary trades to receive assisted passage.” Those who did not have the money, signed a promissory note requiring repayment at £5 every three months until the debt’s “discharge,” the first repayment due six months “after landing.”3

Potential immigrants had to “be of sound mind, good health, and good character.” Other stipulations included: “No single man above the age of 40 years, no person above the age of 50 years unless a member of a large family, and no person above 60 under any circumstances.”4 The candidates had to come from rural districts, the men needed to show previous employment as agricultural labourers, and young married couples were encouraged.

Free passage was provided to single women “accustomed to domestic service, who can bring satisfactory proof of good character, and who are between the ages of 15 and 35.”5

The colonists already in Canterbury must have been desperate for extra home help—or potential wives—because only three days after the original invitation, the Superintendent of Canterbury, William Rolleston, sent a telegram:

I wish the number of single women increased to one hundred more than originally recommended; or if that number cannot be taken, as many more as the ships that have not left when your advice reaches England can bring out.6

The New Zealand government approved his request.

_______________

… two small farmers in Cornwall who wanted to immigrate could not because they “had not the means to do so.”

In 1871, Julius Vogel, then New Zealand’s Secretary of State, had to cast the net for his expansion plans outside Britain.

Until then, advertising for immigrants had been targeted at England and Scotland, but these countries suddenly experienced their own “general revival of trade.” A substantial increase in the price of tin lead, for example, produced a corresponding demand for miners in Cornwall during a time when the more established and geographically closer United States and Canada offered cheaper fares—and a much shorter transit—than New Zealand.

The new prosperity in Britain did not reach everyone. An immigration agent told Dr Featherston that two small farmers in Cornwall who wanted to immigrate could not because they “had not the means to do so.” Their furniture, farming implements and stock had been “distrained upon” to pay the rent. Another “hard-working general labourer” had saved a fraction of that needed to comply with New Zealand immigration costs and confessed that not only could he not hope to immigrate, but in old age would “have to seek relief from the parish.”7

… single men—because of their independence from family ties and potential to renege—paid £8…

The single women who received free passage to New Zealand were employed as cooks, housemaids, general servants, or dairymaids.

Prices charged to “assisted immigrants” fluctuated. Agents—who received a commission of at least £1 for each landed adult immigrant—bargained for trade. Married couples with two children paid £5 per adult. Those with more than two children had to pay a full adult fare for each child older than 12 and half fare for children younger than 12. Infants younger than a year were not charged but single men—because of their independence from family ties and potential to renege—paid £8 and, if they signed promissory notes, repaid more than married couples.

Immigrants made their own journeys to the ports of departure. For the Poles, until 1876, this was Hamburg. They were expected to arrive with “suitable and sufficient clothing for the voyage” and pay for their “outfit for bedding and mess utensils” aboard ship. In Germany, this payment was not to exceed 10 thalers. Their British equivalents paid 25 shillings.

Even with promised free passage, single women were tough to find. Featherston made a trip to Scotland and had a meeting with “ladies and gentlemen connected with Industrial Institutions” who said they could supply him with “suitable female domestics.” He soon found out that this was a ploy by the said “ladies and gentlemen” to “get rid of the inmates of their Reformatories.”8

With expenses mounting, Dr Featherston devised a plan to accommodate another necessary import—railway plant—on the emigration ships. The human cargo would reduce the cost of freight of the industrial cargo and vice versa, Dr Featherston told Colonial Secretary William Gisborne in November 1871.9

In a letter dated 7 March 1872, Dr Featherston said that he had arranged a contract with German emigration agents Messrs Louis Knorr and Company, who advertised that two ships would sail from Hamburg to New Zealand that May. Once Poles like Albert Watembach found out about the opportunity to emigrate, they had no time to lose.

“In some places there were opportunities to catch a canal boat, but they talked about walking and walking.”

The distance from Rytel to Hamburg is about 600 kilometres on today’s roads. Debate among Ray’s fellow members of the Polish Genealogical Society concluded that the wealthier people from the district would have taken the most direct route of the day—to the port city of Gdańsk, by sea to Kiel, and then south along the Kiel Canal to Hamburg.

“Poorer migrants like the Gierszewski, Borkowski, Watembach, Grochowski, and Szymanski families went the cheaper, overland way. It was impossible to go all the way by train, as the tracks stopped in Poznań. In some places there were opportunities to catch a canal boat, but they talked about walking and walking.”

The star, the evening edition of the lyttelton times, published a story about the friedeburg on 2 September 1872:

Amongst the married couples, one immigrant was pointed out as having walked from the Russian frontier to Hamburg (a distance of about 800 miles) with his wife and five or six children, sleeping at farm houses and oftentimes in the open air on their way to join the ship.10

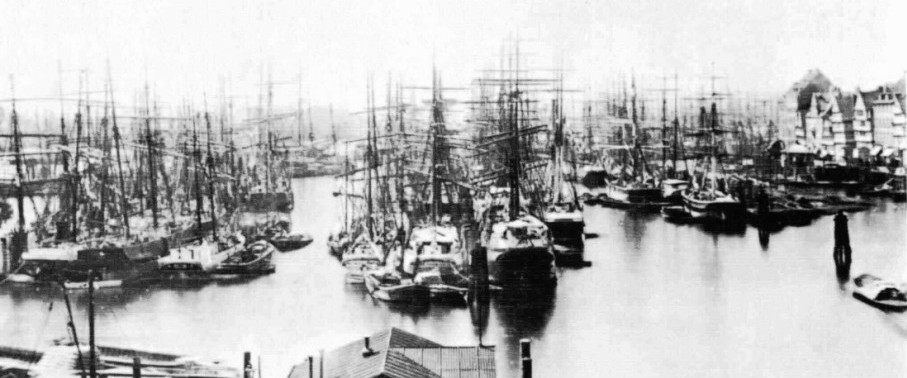

In the 1870s, Hamburg’s busy port hummed with ships arriving and departing. Among the throngs, immigration agents coerced potential passengers. For rural, illiterate Poles, the hustle and babble of their forced second language must have been bewildering. It is no wonder that some had the impression that they were going to America.

Hamburg harbour in 1875.11

Ray: “Many untruths were told. Some German agents offered free travel and free land in America, and some of the families who arrived in New Zealand sincerely thought they were joining their relatives already in America.”

Those who embarked on the friedeburg waited in lodgings at the port while agents gathered up sufficient passengers. A Mr Slomon is mentioned several times in official correspondence between agent-general Featherston and his New Zealand superiors. Slomon, described by Featherston as “one of the wealthiest merchants and the largest shipowner in Hamburg,” took “personal responsibility for the venture.” He seemed keen to create a favourable precedent with Hamburg’s first immigrant export to New Zealand.12

… the inadequacy of the medicine chest and … the “nature of the medical comforts” were “absurdly chosen.”

The friedeburg dropped anchor at 4pm on 30 August 1872, at Godley Head, outside Christchurch’s Lyttelton harbour. It had left Hamburg on 19 May. Captain Kopper commanded the three-masted 784-ton iron vessel, described as “commodious, sufficiently ventilated and in fair order” and “undoubtedly admirably adapted for the conveyance of emigrants.”13

All the passengers were vaccinated. One 10-month-old died of marasmus. The six births included a son to 26-year-old Marianna Groszyńska (named Groskowski on the passenger list) travelling with her 35-year-old husband, Piotr, and two-year-old Józef. They named the baby Marian Piotr.

In his report, the ship’s surgeon-superintendent, Dr J de L Temple, pointed out the “injudiciousness” of providing salted fish with a limited supply of “decidedly bad” drinking water. The doctor complained about the inadequate medicine chest, and the “absurdly chosen… nature of the medical comforts.” He had had no use for the 240 bottles of gin or the 55 “dozen of beer” but would have liked more “pails, brooms, mops [and] scrapers.”14

The friedeburg carried 241 “statute adults,” including Albert Watemburg’s family and nearly 100 other Poles. The 297 people on board comprised 53 families, 33 single men, 61 single women, 82 children younger than 12 and, in the end, 15 infants.15

Immigration officers noted there had been no schoolmaster for the “unusually large” number of children, and the doctor complained that there was no matron for the single women, who had given him “much unnecessary trouble” thanks to their being “destitute of any employment of amusement.”16

Dr Temple advised against shipping Scandinavians and Germans together again, after he heard that memories of the 1864 Denmark-Prussian war had caused the friction between them.

Scandinavians made up the largest ethnic group on the friedeburg, Poles the second. Temple described the few “real” Germans as “well-meaning, industrious, sober, and honest” but took a dislike to the Poles.

Temple: “The Poles, who also speak German, on the contrary are lazy, indolent, and dirty in their habits. I am afraid they will, with few exceptions, be found comparatively useless, and I should certainly not consider it desirable to import any more of them.”17

Featherston noted that Temple “speaks German as fluently as a native.” Perhaps the doctor experienced Polish reticence towards someone who represented the same German authority they were escaping.

According to the star, 2 September 1872, on arrival:

[T]he large group of immigrants presented a somewhat novel spectacle. Three or four nations were there represented…the Germanic, the Germanic Polish, the Norwegian, and the Danish, all chattering away in the language and dialects of their respective countries…

…It was a curious fact, that while those on one side of the vessel (Polish-Germans) complained about the insufficiency of food; those on the opposite side (Norwegians and Danes) expressed entire satisfaction. The former were asked how they could account for this, and their reply was that the latter were richer than themselves, and besides bringing more comforts with them, had money enough to enable them to procure what they wanted. The same thing, however, was noticeable in the single men's compartment; here the Danes and Norwegians were perfectly satisfied with their treatment on board, while a few of the Germans and Polish-Germans complained of the quality of the water and the insufficiency of the dietary scale.

The captain and doctor speak very highly of the conduct of the Norwegians and Danes and most of his own countrymen during the voyage from Hamburg. We were pleased to observe the cleanliness of the ship in every part, and it is doubtless owing to the care taken in this respect that the health of the passengers has been so successfully maintained.

In contrast to Temple’s assessment of the new immigrants, a writer from the star described the entire group as a “very good selection” who would “have no reason to regret coming to New Zealand.”18

_______________

After 102 days at sea there is no doubt the friedeburg passengers appreciated their first few nights on land. Trains took them to Christchurch’s Addington immigration barracks, which received more than 90 applications for domestic servants. The custom was to “throw open” the barracks to employers after three days. The star of 6 September 1872:

There was a large attendance of employers, and the barracks wore a very busy aspect from the hour of opening to the close. The proceedings were also of a somewhat more animated character than usual, owing to the extra talking, which had to be done in consequence of all business negotiations being conducted through interpreters.19

The single women’s lack of the English language did not deter English employers from engaging 42 of them on the first day. Little more than a week later, all the single women had jobs as cooks, general servants and nursemaids. Their annual wages respectively were £30, £20, and £12–£18, with board. Twenty-eight of the single men picked up work as general farm servants (£30–£40 “and found”) and labourers (£25–£30 “and found”). A tailor, a 19-year-old single man, was employed at £52 “and found.”

Men with families did not get jobs as quickly, and by 9 September 1872, fewer than half had taken up positions as carpenters and blacksmiths (£45) or farm labourers (£40–£45). Both types of employment promised a bonus of £10 a year.20

Ray: “Some of the Polish families went to Pigeon Bay. A Mr Holmes came one day with a Herr Rudenklau, the German engineer on the Lyttelton tunnel, to offer accommodation and work for 14 family men to ‘stump’ the land to make it arable. They got there by small ship. Others were sent out onto Banks Peninsula to cut trees and, in season, to collect cocksfoot grass seed, which returning sometimes as much as ₤30 for two months’ work—almost a years’ income—and which meant they could repay thier loans quickly. They planted potatoes, vegetables, and herbs close to the cottages everywhere they worked, as in Poland growing their own food was a necessity for all working people.”

The Watemburgs and other Polish families later moved to Marshland, north of Christchurch city. The name of the area is self-explanatory—it was a swamp, predominantly owned by Messrs Reece and Rhodes, who were looking for men to build drains and break in the land. Reece found the Poles at the camp on the Banks Peninsula and offered them land leases of £1 an acre for 30 years, for five- and 10-acre blocks. (See marshland: the place where flax grows profusely.)

The Ōtukaikino reserve north of Marshland is one of the few remaining original wetlands in Christchurch. An on-going restoration project controls the raupō (reeds) by cutting it back and curtailing its spread by planting native sedges, grasses, ferns, flax and trees.21

Descendant of the Borkowski and Gierszewski families, Margaret Copland, shows the raupō’s natural height. Springs of varying depths still abound and a person walking among the raupō could still be swallowed. Visitors to the Ōtukaikino reserve are warned to remain on the boardwalk.

_______________

The Poles may have left their Prussian oppressors, but their names still carried their German baggage. Ships and immigration manifests in New Zealand under the heading “place of birth” often listed “Germany” or “Prussia.” This was theoretically correct—it would be another 46 years before the Second Polish Republic emerged out of the First World War—but it gave the wrong impression.

Below is a list of the surnames of the Poles on board the friedeburg, with some spelling variants after the most likely original Polish spelling.

- Arczikowska/ Archikowska/ Arezikowska/Arozikowska/Otrazikowska (single woman)

- Borkowski/Burlowski/Boloski (husband and wife)

- Borezenski/Borezinski/Borcinski/Borczinski (single woman)

- Burchard (family of six)

- Burysek/Burgsiek (family of five)

- Cierzinska/Cierzinka/Cierczicka (single woman)

- Felski/Feetsku/Feltsku/Falska (family of three)

- Gierszewski/Gierzewski/Georgewski (family of four)

- Grochowski/Grockowski (family of three)

- Groskowski/Grockowski (family of four with fourth member, Marian Piotr, born at sea)

- Gurni/Gerki (family of three)

- Jablonski/Jablowski/Jablinski/Fuklinski (family of three)

- Jakochowski/Jackshowski (single woman)

- Jaroszewski/Jarozewski/Jarozwski/Jarosgewski (family of six)

- Kaczorowska/Katzarowska (single woman)

- Kotlowski/Kottlowski/Kattlowski (family of six with sixth member, Antoni, born at sea)

- Kurek/Kurck/Knurek (family of three)

- Liserka/Lisiecka (single woman)

- Piekarski/Pieharski (family of three)

- Szutkowski/Shulkowski/Schulkowski/Schilkowski (family of three)

- Szymanski/Schimanski/Schiemanski (single man)

- Tuszynska/Tuschinska (single woman)

- Warczynska/Warezynska/Wurezinska (single woman)

- Watembach/Wattembach/Watemburg/Wartenbach (family of five – by then Franciszek was six months’ old but he did not survive the journey)

- Wischniewski/Wischniewzki/Urschniewski/Wirthniewski (family of four)

- Wischnowski/Wischniewzki/Urschnowski/Wirthmowski (single man)

- Woszewiak/Woczewick (single woman)

- Zdonek/Indonek/Dunick (family of five)

- Zulkowski/Inlkowski (family of three).

Several of the families were related, or were neighbours in Prussian-occupied Poland, but even if that were not so, they would have made friends during the weeks they spent together getting to and in Hamburg, and on the friedeburg. They shared a common language and background, and it was inevitable that when they first arrived in New Zealand, they created their own communities.

Some of the friendships turned into marriages, and their family stories and names intertwined. They form the basis of our searchable database of about 1,400 of the early Polish settlers in New Zealand in the 1870s and 1880s, list of early polish settlers. We welcome input. Please let us know if a name is missing.

Twelve ships carried those Poles to New Zealand. By the time the last, the fritz reuter, arrived from Hamburg for the second time, New Zealand had ceased its assisted immigration. After 114 days at sea, those passengers had to remain on board until their passage was paid.

A German diplomatic intervention ended the impasse, but the Poles had tasted what life was to be like in a new colony where they were needed for their labour, but where they were not particularly wanted.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2016

Updated August 2024

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

All Papers Past citations from newspapers and the Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), are through through the National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - I have taken gender inspiration from Jan Matejko’s 1864 painting, Polonia, which depicts Poland and Lithuania as two women being shackled by a blacksmith as Russian officers and soldiers look on.

- 2 - The single quotation marks are deliberate, to show that the methods used to extracted land from Māori by the government of the new colony, and dubious opportunists like Edward Gibbon Wakefield of the New Zealand Company, remains a contentious issue.

- 3 - This and the extracts in the following two paragraphs from AJHR, 1871, D-3, PAPERS RELATING TO IMMIGRATION. 1– GENERAL REPORTS AND CORRESPONDENCE, p 37.

- 4 - Ibid.

- 5 - Ibid.

- 6 - Ibid, pp 38 & 39.

- 7 - AJHR, 1872, D-01a, CORRESPONDENCE – LETTERS FROM THE AGENT-GENERAL, PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, WELLINGTON, pp 5 & 6.

- 8 - Ibid, p 4.

- 9 - Ibid, p 3.

- 10 - Star, 2 September 1872, p 3, IMMIGRANTS BY THE FRIEDEBURG. Papers Past,

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/4823950. - 11 - Image from: http://orsted-jensen.weebly.com/scandinavians-in-pre-1914-australia.html

- 12 - AJHR, 1872, D-01a, CORRESPONDENCE – LETTERS FROM THE AGENT-GENERAL, PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, WELLINGTON, page 12.

- 13 - AJHR, 1872, D-01b, FURTHER CORRESPONDENCE WITH THE AGENT-GENERAL, LONDON, p 3.

- 14 - AJHR, 1873, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND: MEMORANDA TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY BY COMMAND OF HIS EXCELLENCY, p 8.

- 15 - AJHR, 1872, D-01b, FURTHER CORRESPONDENCE WITH THE AGENT-GENERAL, LONDON, p 3.

- 16 - AJHR, 1873, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND: MEMORANDA TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY BY COMMAND OF HIS EXCELLENCY, p 2.

- 17 - Ibid, p 8.

- 18 - Ibid, Star, 2 September 1872, p 3, IMMIGRANTS BY THE FRIEDEBURG.

- 19 - Star, 6 September 1872, p 2, LOCAL AND GENERAL: THE SCANDINAVIAN IMMIGRANTS. Papers

Past,

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/4826324. - 20 - AJHR, 1873, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND: MEMORANDA TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY BY COMMAND OF HIS EXCELLENCY, p 3.

- 21 - This 13-hectare freshwater reserve is accessible off Main North Road, between Chaney's Corner and the Belfast end of Christchurch's northern motorway. Photographs: B Scrivens.