The Kurowski-Crofskey Family

In May 1990 nearly 900 people gathered in Bell Block, New Plymouth, to remember Franciszek and

Franciszka Kurowski who, with their four children, left Prussian-partitioned Poland in 1876 and sailed to New Zealand aboard

the fritz reuter.

Two of their great-granddaughters, Helen Hammond and Margaret Parker, first broached the idea to another cousin, Sandra

Singleton. They heard that Sandra’s husband, Richard, had written training manuals, and felt he could tackle the family

story. The gathering was the culmination of years of family collaboration and the book, the

kurowski family in new zealand 1876–1990.

Some of the descendants posed for this photograph. Seated at the front behind the children are some of Franciszek and Franciszka’s grandchildren, from left: Tom Ryan, Mabel Autridge, Lillian Raill, unidentified, Myra Cocker, Helen Meads, Elsie Crofskey, Arthur (Mick) Crofskey, Joyce Smillie, Lillian Hamilton, three more unidentified women, Gladys Crofskey, unidentified and Maude Seamark. If anyone can help identify others, please get in touch with us through the link on the home page.

Sandra, in the book’s introduction: “There was little solid information by way of

written material or photographs. There were several children of the two brothers and two sisters surviving at the time but

their information was limited, as anything they had been told was either forgotten or, in the case of photos and written

material, mainly lost. Time also meant the facts became vague.”

Sandra in March 2017: “Remember in those days the internet was in its infancy and even scanning photographs was only

just beginning. All correspondence was done by snail mail.

“Some of the older relatives were reluctant to share their memories. One man told us his grandmother, Rose Blake, took

him into the sitting room when he was quite young and served afternoon tea with crème wafer biscuits and told him the family

story. All he could remember was the honour of being in that front room and the crème wafer biscuits.

Mary Maddern (Rose Blake’s granddaughter), Doug Crofskey (Jack and Jane Crofskey’s grandson), Fay Evans and her mother Lill

Raill (Ryan family) and Shona Spelman (Joe and Barbara Crofskey’s granddaughter) joined Margaret and Helen in urging their

families to hunt through their bookcases, boxes and attics for information and photographs. Richard spent hours researching

written record in the local library and trawled through history books and helped Sandra compile the book.

Sandra gave me a copy of the family book in September 2013. That book, subsequent interviews with Sandra and another cousin,

Pat Alvis, and additional information now available to researchers, forms the basis of this story.

As with any large family I have no doubt that some stories have been left out, or remembered differently by different people.

In a sub-menu, kindness and courage, we have transcribed two letters that Mabel Autridge

(née Ryan) wrote to Sandra. If anyone would like to make a further contribution to this family history, please get in touch

with us through the home page.

—Barbara Scrivens

March 2017

STRENGTH IN ADVERSITY

by Barbara Scrivens

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

But two things stand like stone,

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own.1

—Adam Lindsay Gordon (1833-1870)

No one saw a boat, laden with newly sharpened prospecting tools, five men, a boy—and possibly a dog—disappear off the West Coast's Big Bay in early June 1878.

As the boat navigated the Jackson’s Bay reef on its way south a few days earlier, Franciszka Kurowska knew that at least one of its passengers, her husband, Franciszek, would have been suffering in the choppy seas. More than three months on the fritz reuter had not cured him of seasickness, but neither had nearly two wretched years in the “special settlement”2 blunted his determination to succeed in their new life as settlers in New Zealand.

… bracing himself in the boat’s cabin during the “fresh” mid-winter weather… Franciszek stood no chance.

Henry Fisher, a prospector hunting for kakapo and kiwi at Big Bay on 13 June, recognised the fly-sheet of a tent tangled among the rocks above the high tide mark. It belonged to a friend of his. Shortly after, in the dimming light, Fisher found a blanket and the corpse of “a stranger” on the beach and “hastened back” to the two other men in the area at the time. The next morning revealed two more corpses and the men alerted authorities to the probability of a boating accident. The subsequent search party found two more corpses but former soldier Franciszek Kurowski disappeared with the boat and the tools.3

Franciszek’s family believe that, embarrassed at his seasickness, he was bracing himself in the boat’s cabin during the “fresh” mid-winter weather. The expedition had spent two days in Jackson's Bay waiting for “heavy seas” to ease. If, as conjecture had it, the boat—once it finally got out—was swamped on a reef about three miles off Big Bay, Franciszek stood no chance.4

Topographical maps of the area show rocky outcrops and steep terrain along much of the coast between Jackson’s Bay and Big Bay. The modern spelling is Jackson Bay.

_______________

Less than two years earlier, Franciszek Kurowski’s faith in the promises he had heard about Jackson’s Bay made him determined to settle his family there. By the time he drowned, they were destitute, and his pregnant widow resolved to leave what is still one of the most remote places in New Zealand.

He met a fractious community, a rain-sodden climate in heavy forest… and a complicated store-keeping system that guaranteed indebtedness.

Franciszek believed the “special settlement” would provide his family with a better future than the one they faced in Prussian-occupied Poland, despite his employment with the Prussian military. The new antipodean colony offered freedom from Prussian prime minister Bismarck’s dominating authority—and the guarantee of a job, accommodation, and alluvial gold intermingling with sand on beaches.

Franciszek did not allow anything to sway him from his commitment to the southern west coast of the South Island and his family’s future there—neither the controversy that embroiled fellow passengers on the fritz reuter once they landed, nor the reluctance of other Poles to travel to Jackson’s Bay.

He did not expect to be met with a fractious community, a rain-sodden climate in heavy forest where crops rotted in the ground, and a complicated store-keeping system that guaranteed indebtedness. He had to build his own accommodation. Work was scarce.

_______________

When the fritz reuter arrived in Wellington on 4 August 1876 its passengers were not allowed to disembark. They believed that they were part of the government’s assisted immigration scheme—created for the new colony under the Immigration and Public Works Act of 1870—but it had become unaffordable and had ended.

The dispute involving the fritz reuter resulted from New Zealand’s agent-general in London sending the immigrants to New Zealand after an apparent order not to do so. The would-be immigrants had, in good faith before they embarked in Hamburg, signed promissory notes rather than pay directly for their fares. Only after lengthy negotiations and monetary assistance by the New Zealand consul for the German Empire, Frederik Krull, were the passengers allowed to disembark several days later.

“Send no emigrants Jackson’s Bay special settlement.”

Five weeks earlier the then-Minister of Immigration, Harry Atkinson, had instructed that “in future no foreign nominations are to be accepted except under very special circumstances.”5 By then the fritz reuter was 11 weeks into what became a journey of more than 16 weeks. The same day the ship docked, Atkinson sent a telegram to the agent-general: “Send no emigrants Jackson’s Bay special settlement.”6

More than 50 Poles from the fritz reuter went north to Taranaki. The Kurowski family joined the more than 70 travelling south to Hokitika. By October 1876, Franciszek and his family had joined other Poles in the Smoothwater settlement at Jackson’s Bay.

Franciszek (32) and Franciszka, née Kamińska, (30) arrived with their children Franciszek (11), Rosalia (4), Johan (2) and Maria (three months). The only other Poles from the fritz reuter to join them in Jackson’s Bay were the Lipiński family, who came from the same village, Riwalde, near Gdańsk.

Robert Lipiński (37), his wife Johana (38) and children Anastasia (9), Franciszek (5) and Johan (2) became the last Polish settlers in Jackson’s Bay, arriving more than a year after the first Poles off the lammershagen.

_______________

Franciszek Kurowski grew up in Prussian-partitioned northern Poland hearing about the adventures and exploits of Gustavus Von Temsky, a professional soldier fighting in New Zealand. Von Temsky had such a reputation for fearlessness and invincibility in battle that when Māori killed him in Taranaki in 1868, they apparently put his corpse at the bottom of the pyre to ensure the complete destruction of his remains.

Kurowski family stories tell of Von Temsky’s writing to Franciszek’s parents extolling New Zealand’s virtues and the opportunities that existed for new settlers:

Fay Evans: “Gran [Maria, then Mary Ryan] always said that her mother told her that Von Temsky encouraged Franciszek and his family to come to New Zealand… Franciszek had a lot of admiration for him as a soldier.”

At the time of Von Temsky’s death Franciszek, 24, had already followed him in one of the few careers available to Poles in their occupied country—the Prussian military. The Kurowski children were born in born in various military camps as the family moved with their father’s postings, Franciszek junior (Frank) and Maria in Riwalde, Frank on 28 July 1865, and Maria on 25 March 1876, less than three weeks before the fritz reuter sailed from Hamburg. Rosalia was born in then Dirschau (now Tczew) on 29 November 1871, and Johan in 1874 in Stargard (now Starogard Gdański).

A Polish historian told Fay that if the family had a piano, they would have had “means of some sort.”

Another of Franciszek’s great-granddaughters, Pat Alvis, believes he came from a noble family, because he was “permitted” to join the Prussian army at officer level, something that allowed his family a more comfortable lifestyle than most other Poles:

“In Poland they were fortunate enough not to be deprived of everything that mattered, like so many other Polish people. Great-grandfather had money and a salary. It didn’t sit well that he had to cow-tow to the Prussians, but he did earn a living.”

The extent of Franciszek’s monetary comfort is not clear. Pat believes he earned enough to engage the services of an English tutor. Fay understood that Franciszek, Franciszka and their two older children were fluent in German and had had piano lessons. A Polish historian told Fay that for the family to have owned a piano, they must have had “means of some sort.”

_______________

Bismarck’s quest for expanding the German Empire forced increased germanisation on Poles living in the territory. Polish schools closed, Polish books, Polish writing, and the Polish language were banned. Was a tutor Franciszek’s way of educating his children outside the Prussian school system? Many Poles refused to allow their children to be schooled in the German language, resulting after several generations, in mass illiteracy .

The consolation of a regular income and education for his children was not enough to keep Franciszek from pursuing an opportunity for a new life in the colony praised by Von Temsky.

Settlers could potentially “leave off work and make a few pounds on the beaches” by searching for alluvial gold.

The impetus came when Jackson’s Bay featured positively in an advertising campaign run in the UK and continental Europe. Emigration agent Julius Matthies circulated German translations of the “General Conditions of Settlement”7 in the Stargard area where Franciszek was stationed.

Pat: “[The agent] was looking for people from Europe who would be prepared to work in remote places in New Zealand. He described a wonderful place right down the west coast of the South Island… Jackson’s Bay… a planned settlement… everything a new settlement of people would need… a proper harbour and even gas lights on the streets… Each settler was allotted a certain amount of land for a house and a further allotment of land for farming—none of which existed.”

The special settlement’s promotional Jackson’s Bay handbook “circulated to induce persons to establish themselves at the settlement”8 promised government houses, 50 acres of land, work and provisions sold at cost plus freight. Settlers could potentially “leave off work and make a few pounds on the beaches” by searching for alluvial gold.9

In the end, the Kurowski family left Prussian-partitioned Poland in a hurry. It is not clear whether this happened because the Prussian military authorities discovered Franciszek’s plans and took offence.

Fay: “Gran said that German soldiers came to their house and told them to leave as quickly as possible. Rose [Rozalia] told Gran that she saw one of the soldiers breaking up her beloved piano. Their father knew one of the soldiers and he helped them get to Hamburg and arranged passage for them on the fritz reuter.”

_______________

Pat: “When they did arrive in Jackson’s Bay there was nothing—except sandflies of course.”

“My great-grandfather had a house built but the climate was so bad that when they planted potatoes, for instance, they rotted in the ground.”

The Polish custom of growing fresh produce for the family proved impossible. Franciszek added his name to the list of settlers forced to rely heavily on the settlement’s general store for basic necessities.

John Murdoch, a Scotsman and one of the first settlers to Jackson’s Bay in January 1875, told the 1979 Commission of Inquiry into Jackson’s Bay:

From the regulations we were entitled to three days work per week per annum for two years… Instead of settlers getting work it was withheld from them until their store account had run up… If the settlers laid out their own money in stores that was given as a reason for not giving them work… Work was given by choice to those settlers who were indebted to the store…10

Robert Crawford, another Scotsman who arrived in the same group as Murdoch, testified:

… the Government reports settlers’ work is valued at a very high rate on their own sections, and at a very low rate for Government work. The price of goods was so high that it was almost impossible to keep out of debt…11

Neither the Kurowski nor the Lipiński names are on the commission’s settler list but both appear on statements showing the amount they earned during their time at Jackson’s Bay, and their outstanding accounts.12

According to the government statement showing the amount paid for labour to each settler, between October and December 1876, “Franz Conronfoki” received £4 12s. In 1877 “Franz Conronfoko” received £11 7s as “day wages” and £110 12s 6d under “contract.”

Between January and May 1878, “F Conrofski” was paid a total of £11 7s for labour, and “F Couronski” £1 2s for contract work. In its summary, the commission used the spelling “Conrofski” and “drowned” so there is no doubt these are Franciszek's earnings.

The settlers had been assured of eight shillings a day for three days a week for the first two years of the settlement. Franciszek arrived six months before that deadline, but still earned no “day wages” in February, March and May 1877, and only six shillings in April. Settlers complained that even 24 shillings a week barely covered their provisions—but in August, September and October 1877, Franciszek received only eight shillings a month.

The more lucrative contract work Franciszek did in 1877—£110 12s 6d—is only five shillings less than the “Total Amount of Stores Supplied” to him at Jackson’s Bay. By the time he boarded the prospecting boat, he still owed £58 19s 1d. Seasickness or not, he needed a job: He had earned barely £22 that year, owed nearly three times that amount, his wife was again pregnant, and the land attached to his house in Smoothwater was unlikely to produce food.13

_______________

Stories of the drowning off Big Bay started appearing in local newspapers in July 1878, many publishing a letter from T F Brenchley, Officer in charge Martin’s Bay Boating Service, to the Commissioner of Police in Dunedin.

The boat, “recently overhauled and enlarged, and made more comfortable for the short sea trip,” left for Big Bay—about 75 kilometres south-southwest of Jackson’s Bay—on 26 May 1878.14 It was “deeply laden with crowbars and other mining tools, which had been taken to Jackson’s Bay for sharpening.”15

The lake wakatip mail said on 25 July 1878:

No survivor (unless he be Kroupki [sic]) remains to tell the story, and therefore the cause of the accident is a mystery. It is supposed, however, that the boat was overloaded and swamped on a reef about three miles from Big Bay.

The dead were:

- Andrew Williamson—a Scotsman from Shetland and almost certainly the skipper of the boat, a well-known pioneer and prospector in the area. He took on the roles of Big Bay’s postmaster, registrar, and correspondent for the lake wakatip mail. Described as “one of the oldest residents—thoroughly up in nautical matters and intimately acquainted with the coast [who] did much for the advancement of the settlement…”16 He received most column inches. Lake Williamson and Andy Flat, inland from Big Bay were apparently named after him, also Andrew Creek farther north;

- HA or Dr Branston—from England (other spellings were Branshon, Bransen, Branschon, Branschon and Branstay), a chemist who took on the role as Jackson’s Bay’s community doctor. He was the “stranger” Henry Fisher found;

- Jeremiah Yell—who arrived in Jackson’s Bay in March 1875, from Orkney, off the north-east coast of Scotland and a ship’s carpenter by trade. Williamson was apparently related to Jeremiah Yell’s wife;

- Jeremiah’s 10-year-old son James;

- John Gabriel—originally from Nova Scotia and living in Martin’s Bay. He was the friend Fisher referred to. His name was also spelt Gebrul;

- Franciszek Kurowski—eventually confirmed as the sixth victim. Because his remains did not wash up on the beach, it took a while for people to realise there had been six on the boat. The various newspapers described him as a Pole living in the “same neighbourhood” as Yell,17 “a German with a wife and large family,”18 and, “like the others, an industrious settler.”19 Spellings of his surname included Kroupki, Cronspki, Kronopki, Kronspki, Cornspaci and C Kroupti.

Seven men formed a search party on 18 June, took a pilot boat around the Big Bay reef and walked along the beach at low tide. William Martin described the scene for otago witness readers:

To the west lay the waters of the Pacific as peaceful as an inland lake; a light breeze off shore in places took off the mirror-like appearance of its surface, except at the long reef, which runs out to sea for perhaps a mile and a half. Its length and direction can be easily traced by rocks rising above the surface here and there, and the breakers rolling in one after another. To-day could be seen a small blue wave rising gradually, gathering height and force as it proceeded, until it stood a perpendicular wall of green water and then toppled over in the centre a matt of white spray, and foam, the ends remaining green and tapering down to the level ocean. Thus it rolled on and on until it spent itself on the rocky shore, a seething, thundering mass of foam and spray. Woe to the unfortunate craft that is caught upon this reef.20

Martin soon found “a mass of human remains.” He identified John Gabriel’s crumpled skeleton by his boots and the few rags still clinging to his bones, and then found Jeremiah. The search party dug graves for the five dead, and left funereal words and a cross made from the wreck of the czarewich. They were later interred at the Arawata Cemetery, but it is not clear exactly where—any original indentification is long lost. Only one of the Yells is mentioned in that cemetery’s records, and that entry is incorrect.21

Reports on the early Polish settlers often comment about their struggle to communicate with other settlers because of their lack of English. What was a Polish man doing with the rest of the English-speaking prospectors? How had he found out about the trip?

Pat heard from her grandmother Mary Ryan that Franciszek’s eldest son, known as Frank, spoke several languages and helped other immigrant families deal with authorities. Perhaps Frank found out about the prospecting opportunity, or his father may have by then absorbed enough of the English language to find out for himself.

_______________

A “perfectly destitute” widow Yell and four surviving children left Martin’s Bay on the next ship to Port Chalmers, Dunedin. Similarly destitute Franciszka left Jackson’s Bay knowing that she had no way of repaying the family’s debt to the store. Resident agent, Duncan Macfarlane, must have been aware of that fact because he wrote in a report on the accident that he had “to render the family some little assistance.”22

According to Florinda Lambert (née Voitre), who documented early Polish history in the Inglewood area, Franciszka and her children arrived in New Plymouth on Thursday 19 December 1878, aboard the colonial steamship stella with a contingent of nearly 100 people from Jackson’s Bay and Hokitika. (See the Voitrekovsky family story on this page for more on Florinda’s ancestors.)

Two local newspapers ran stories on Franciszka’s arrival in New Plymouth.

The taranaki news, under a headline A Case for the Ladies, on Saturday 28 December 1878:

A German [sic] widow with four children and near her confinement, is in Marsland Hill Immigration Barracks, destitute; she is off rations. Her husband was drowned, and, as all her country people left Jackson’s Bay, she availed herself of the offer of the Government steamer, and came away. She has the offer of an immigrant cottage, but has not the means to buy a little furniture to put in it, to make herself and children a little comfortable. Mr Weyergang has kindly consented to receive donations for the poor person.23

The taranaki budget and weekly herald, in an untitled piece the same day:

Amongst the families that have been brought here from Jackson’s Bay is an Italian [sic] woman with five or six children. She is a widow, her husband having been drowned only a month or two since. The poor woman is near her confinement, and, of course, unable to gain a living for herself, at the present time. This is really a case for the benevolently inclined to take in hand, and we feel certain the attention only requires to be called to the case for relief to be afforded to the poor woman and her family. We hear that a tradesman in the place has taken her eldest boy, a lad of about 12 years of age, into his service, engaging him for five years at a very high rate of wages. This is a very benevolent act on his part for he is not likely to get much value from the boy’s services for some time to come.24

Was New Plymouth businessman Newton King the benefactor mentioned above? te ara, the encyclopedia of new zealand described King as a clerk for merchants and shippers at the time that Franciszka Kurowska and her children settled in New Plymouth. The encyclopedia writes that by 1881 King had established himself as an auctioneer, stock salesman, commission agent, and a general merchant. The family story that Frank worked for Newton King is borne out by Frank’s purchase, in 1893, of a town section in Midhurst, where he opened his own general store.

Benjamin, later known as Joe, was born in New Plymouth on 21 March 1879.

Franciszka’s knowledge of herbal remedies probably saved the life of Frank Fabish's wife, Rose, who was “very sick” after childbirth.

Franciszka rented a cottage near the New Plymouth racecourse, kept a goat for milk, some pigs, and made a living washing and ironing, and acting as a nurse and midwife. She charged a shilling a time for delivering babies, sometimes walking miles to the expectant mother.

Another of Mary Ryan’s granddaughters, Sandra Singleton, collated information for the book the kurowski family in new zealand, 1876-1990. Among its stories is one that recalls how Franciszka’s knowledge of herbal remedies probably saved the life of Frank Fabish’s wife, Rose (née Wiśniewski), who was “very sick” after childbirth. The doctors had apparently given up, but Franciszka cured her with a cowslip mixture she made with plants from her garden.25

Her grandmother Ryan told Pat that Frank continued his translation services for Polish settlers faced with officialdom and court, and that another Taranaki merchant, Chew Chong—known for exporting fungus to China—also employed him as a translator. (Several of the Polish families in Taranaki supplemented their incomes by collecting the fungus, or ‘Taranaki wool.’)

While Frank worked, Rose, Johan (John or later, Jack) and Mary became pupils at a church school on Powderham Street. A curtained-off section became a temporary classroom for the pupils. The three children walked there and back through Pukekura Park, where several Polish settlers were employed in its construction.

Sandra found reference to her great-uncle John in the New Plymouth Central School records for 1885, but nothing for Rose nor Mary. Apparently John was “disruptive” in class.

Fay: “Gran definitely went to a Catholic school at some stage, because she often related stories of the nuns, one in particular who was really mean to an orphan boy… always strapping him. One day Gran grabbed the strap and threw it out of the window, and was told not to come back. Whether she did or not, she could definitely read and write well.”

_______________

By 1880 Franciszka had taken in two boarders, brothers Gabriel and John Schnell, whose mother had died. Their father, also John, lived in Midhirst and visited his sons regularly. He had emigrated from Austria and was breaking in a property in York Road, where he lived with his two younger children. Franciszka became his housekeeper in Midhirst and married him in 1885. Alternative spellings to his surname are Gschnell, Geshnell and Schgnell. On their marriage certificate, John’s name is spelt Schgnell and Franciszka’s, Cammisky, a version of her maiden name, Kamińska. She and her new husband had two more sons, Leonhard in 1888 and Benedict in 1889.26

Franciszka’s daughter Mary told Pat how she and her younger Kurowski brothers and sister did not approve of their stepfather—Rose to the extent of running away from his house in 1882. If the ages on the ship’s manifest are correct, Rose would have been 11 at the time. She found work in a hotel in Patea.

Franciszka’s move to Midhurst ended her son John’s formal education. According to Pat, he found farming work “very early in life.” The group photograph below, taken in felled bush in the early 1890s, includes both John (second from left) and Joe (far left) preparing to lay railway line. By the time John married at 20 he had a reputation as “quite a handyman” and another as always being well-dressed. If you recognise any of the other men in the photograph, or have a better version that you are prepared to share, please contact us through the get in touch option on our home page.

Mary remained close to Frank, who became a father-figure to his siblings after Franciszek senior died. She had a “great affection” for her younger brother Joe. After they moved to their stepfather’s house the two were employed on a nearby farm weeding carrots, which Mary remembered for their frozen fingers. She recalled the night she and Joe spent in a rata tree (Metrosideros robusta) after they climbed towards Fanthams Peak on Mount Taranaki to view bush fires raging in the district, and left it too late to return home.

Both Mary and Joe were enrolled at the Waipuku School in Stratford. Mary was admitted in November 1887, her birthdate recorded as a year younger than she was. Joe was admitted in October 1889, his birthdate recorded as two years younger than he was.

According to the family story, Joe lived with his mother and stepfather for no more than two years. He was apparently 10 when he walked south to Cardiff and found a job that paid in food, clothing, and education. Cardiff borders Stratford and maybe Joe decided to live there because it was closer to the school.

When that arrangement stopped, Joe found work on a farm in Eltham. At 14 he was felling trees and supplying logs under contract to buyers in Inglewood. Like his older brother John, Joe married at 20 after leasing a farm in Surrey Road, Tariki.27 His bride was Barbara Stachurska, whose parents and older siblings had arrived in Wellington on the shakespeare in January 1876.

The Kurowski-Crofskey family book described life at the Schgnell’s York Road property:

The first creamery was not opened until 1892, so all the milk had to be processed at

home. The milk would be left in flat dishes and skimmed of the cream the following day. Butter was made in wooden churns, and

could then be used at the store in exchange for flour, sugar, tea etc. Money was a rare commodity in the early years, and

butter was accepted at most stores.

The remaining milk, “skim dick,” was used by the family for drinking and cooking, including making bread.

One other form of income available to pioneer families was the collection of fungus from the rotting trees and logs. Chew

Chong… started buying fungus, or “black gold” as it was locally known, and exporting it to China. Prices

were in the range of 1d to 4d a pound, and it was possible for settlers to make as much as 10/- a day.

The family cooked mainly on an open fire or in camp ovens, and hanged smoked food from the house rafters. The surrounding districts supplied the occasional fish, and eels.

Religion played an important part in the life of the early Polish settlers. There was no Catholic church in the Midhurst area, so they walked the nine miles to Stratford for Sunday Mass, their route along a rough bridle track and over creeks.

In the early days, settlers bought supplies in Stratford. With the menfolk often working elsewhere, it was up to the women to carry the sacks of flour and sugar back home.

_______________

Life changed for Frank Crofskey when a fire at his Midhirst store in 1895 set off a chain of events. Several newspapers ran almost the same sentence:

FIRE AT MIDHIRST. (Per United Press Association.) NEW PLYMOUTH, March 28. A wire to the Herald states that Crofski's store at Midhirst was destroyed this morning by fire at 2 o'clock. The insurance is £357.28

Within nine months, Frank had moved to Thames and, according to an article in the thames star, 10 December 1895, had “commenced business as a grocer and fancy goods dealer.”

During the next few weeks the same newspaper ran more than 30 advertisements for Frank’s two stores, one “next to Mr F Trembath” and the other “in the shop near the Karaka Bridge formerly occupied by Wm [sic] J Simmonds.”

In 1896, Francis registered a son, Frank John Crofskey, born to him and a Mary Ann. Although there is no New Zealand marriage record, Frank apparently had a liaison with Mary Ann Street (née Stevens) after she had become estranged from her husband. At the time Mary Ann had five other children.

Frank moved to America and opened a general store in San Francisco. His stepbrother Gabriel joined him. By the end of 1901, his stepfather, and stepbrothers John, Leonhard and Benedict—then aged 24, 11 and 10—were also in America.

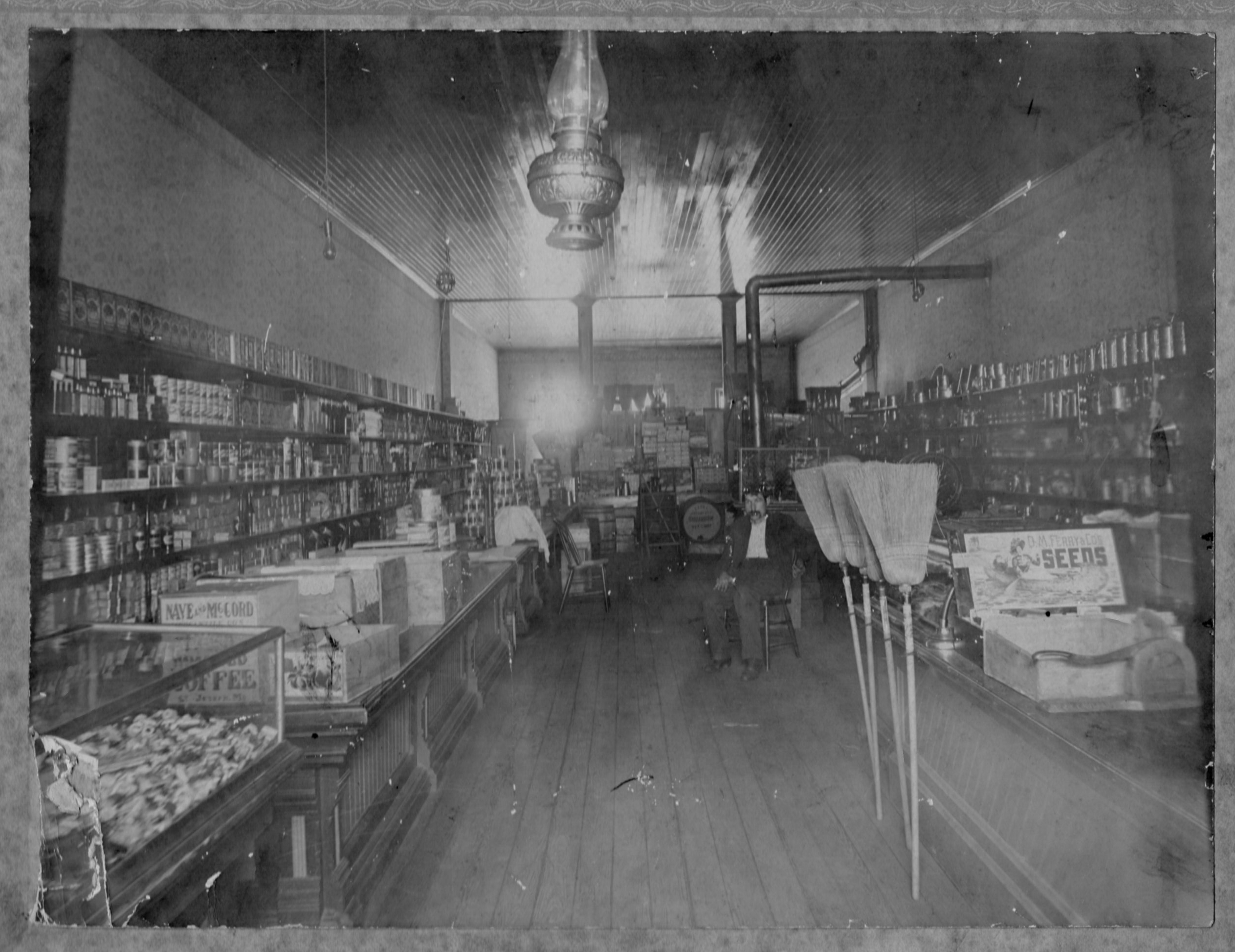

The photograph below shows Frank in his American shop in 1901. He changed his name to Frank Stockton. The family story is that Mary Ann, their son Frank John, and Mary Ann’s second child, Kate, born in 1890, accompanied Frank to America and that the three sailed to Sydney in September 1902 under the Stockton surname. Frank followed in the December.

According to Australian family sources, Frank and Mary Ann had a further two children in Australia before “Frank Crofski Stockton” married “Katie Street” on 16 August 1909. Their New South Wales marriage certificate shows Frank as a “bachelor.” He died on 11 January 1914. His death certificate lists six “living” children from the marriage: Minnie (7), John (6), Gladys (5), Annie (4), Nellie (2) and Rose (1).

Frank in his San Francisco shop, around 1900.

_______________

Franciszka chose to remain in New Zealand. She lived nomadically wherever her daughters, daughters-in-law, and others needed her midwifery skills. Her presence remains in the intricate crochet pieces and lace that some of the family still have.

Before Frank left Midhirst, he gifted his brother John his portion of the section adjacent to the general store. Frank and John had bought it jointly and John lived there with his new wife, Jane Potroz, after they married in 1894.

It is unclear how many children Frank eventually had. Rose married Ernest Blake and had 15, John and Jane had 13, Mary married Martin Ryan and had nine, and Joe and Barbara (née Stachurska) had 10.

Franciszka Kamińska Kurowska Schnell died in 1904 and is buried at the “old” Midhirst cemetery under the name Frances Schnell. With her is granddaughter, Mary Rose Ryan, who died of diphtheria as a six-year-old in 1910. A visitor can find their names on the memorial wall outside, but their headstone lies among those ruined through neglect and grazing by cattle, and now sheep.

Among the trampled gravesites in the old Midhirst cemetery is the headstone Franciszka Schnell

shares with her granddaughter Mary Rose Ryan (top) and this stone, with Franciszka's first married name, placed by her

children.

The cemetery, below, closed in 1995.29

_______________

Kurowski had become Crofskey.

Rose, John, Mary, and Joe all married under the Crofskey name, Rose the first in 1890. Even with an English-sounding name Mary’s official marriage record, to Martin Francis Ryan in 1900, managed a spelling mistake. The register says “Croskey.”

The siblings all reared their large families in a typical Polish atmosphere of shared work revolving around the home.

Pat remembers her great-aunt Rose as a formidable woman. Her youngest daughter, Irene Joyce Smillie, agreed that her mother’s rules were demanding but, with so many children, they had to be. Rose adhered strictly to her routine:

Monday – washing;

Tuesday – ironing;

Wednesday and Thursday – miscellaneous;

Friday – cupboards, knives and silver;

Saturday – large kitchen washed and polished, all shoes and boots cleaned (often referred to as booting day);

Sunday – a day of rest, some mending, crochet or fancy work.

Irene: “As a housekeeper, and practising what she preached, one can remember how wonderful she was with her skills as a cook. When a pig was killed, every part of it was used, the runners cleaned for sausages, the bladder for storing lard, the blood caught for black pudding, the liver used for liver sausages, the head for brawn, hocks and trotters pickled in brine and the rest cured for bacon and ham. The trimmings from the hams and shoulders were used to make a delicious smoked sausage.

“I can also remember the wonderful apple cider and ginger beer. All types of pickles, sauces, chutneys, jams and preserves, cheese, potato pancakes, doughnuts, mouth-watering Easter buns, and she was famous for her cream puffs, pastry, scones and so much more.”30

Rose learnt her pastry skills from a French pastry chef at the Patea hotel. Pat remembers how Rose “would have the table brought out under a huge tree in the shade, don her white apron and make pastries the like of which you’ve never tasted.”

Barbara Crofskey’s family recalled “with clarity” her cooking skills, especially her kiełbasa (smoked sausage) and salceson (a delicacy made from duck blood), and her always-popular contributions to local fetes.31

Meanwhile, Mary filled earthenware crocks with blackberry and raspberry jam, pickled onions, and sauerkraut. She also made her husband’s favourite blackberry wine. Every year potatoes covered an acre of land, along with beans and peas.32

Martin and Mary Ryan with their children David and Mary Rose outside their first house, which Mary's brother John helped build, in Surrey Road, Tariki, near what is now the boundary of Mount Egmont National Park.

Sandra Singleton: “Farming must have been difficult as it was so cold in the winter, the ground was boggy and it was all heavily forested to begin with. After Mary Rose [their eldest daughter, born in 1903] died [in 1910], they built another house, as the old one had such sad memories. They rented it to the York Road School teacher.”

With Mary Rose’s death, her mother poured her energy into helping finance building the new house, declaring the existing one “inadequate” for their growing family. She leased Melrose House in Stratford, moved there with her daughters, and took on boarders. Martin remained on the Midhirst farm with their sons. At the time David was nine, Frederick five, Lillian three, and Mabel a year old.

Sandra: “The boarding house had a marvellous reputation for both the food and the friendliness of Mary and her family. Mary would prepare a cooked breakfast for the 26 all-male boarders, plus a packed lunch and large dinner. She would also prepare baking for the men left working on the farm.”

David and Frederick, Pat Alvis’s father, took on more farming responsibility when Martin found a job at the York Road quarry.

On Sundays, Martin and his sons walked to Stratford to attend Mass and visit the family. Maude and Thomas Ryan were born in Stratford. The Ryans sold the boarding house business at the outbreak of World War I and the family again lived together on the farm.

Pat’s Stratford High School Latin teacher recognised her surname—he had been one of Mary’s boarders.

“In those days everyone knew everyone, or of everyone else, and he probably knew Dad too because Dad was going there on Sundays.”

_______________

Rose Crofskey met Englishman Ernest Pippin Blake in Patea. He farmed a 1,000-acre grazing block in Opaku between the Patea and Whenuakura rivers. They married in 1890 but Rose refused to move to the isolated farm until a school was established for their growing family. Then, the nearest one was 12 kilometres away on roads impassable in wet weather. Ernest, elected to the Whenuakura School board in 1898, petitioned the government’s education committee for a second school in Opaku. By 1900 the Opaku School opened with 20 pupils, five of them Blakes—Ellen (Nell), Abel, Mabel, Ethel and Annie.

The Blakes moved from Opaku two years after the school opened but did not give up their land. Once Nell, their eldest child, married, she and her family lived there.

Rose and Ernest bought a farm in the Waverley district and Ernest looked to other businesses: Within two years his Waverley Proprietary Cheese Company, established in 1903, produced 60 tons of butter and 50 tons of cheese. He bought creameries in Kohi, Manutahi and Maxwell, a blacksmiths, a wheelwrights and a “picture theatre” in Waverley—and was also a Justice of the Peace.

The Blakes’ lifestyle necessitated regular entertaining and Rose asked her sister Mary to help her at Waverley. This gave Mary the opportunity to leave her stepfather’s farm but the younger sister did not always appreciate Rose’s bossy nature, which led to Mary confirming her relationship with Martin Ryan.

Pat: “My grandmother had continually refused his proposals until one day Rose went too far with her autocratic manner, so Mary caught the train to Eltham with the thought she would tell Martin she would marry him. However, Martin Francis Ryan had waited long enough and was already on a horse on his way down to Waverley to propose again… eventually they met up and were married in Eltham.”

Mary (standing) with Martin and their unnamed bridesmaid on their wedding day in July 1900.

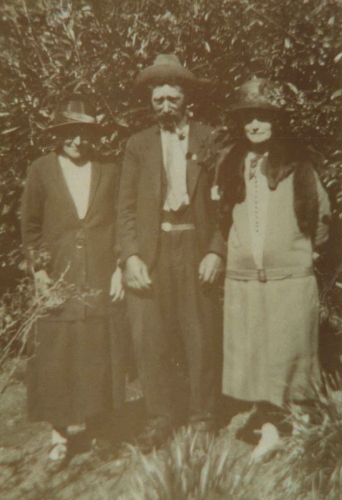

Joe Crofskey with his sisters Rose Blake, left and Mary Ryan.

Ernest Blake had just started a pedigree Jersey breeding programme when he died in 1919. Rose, who loved horses, continued the venture. She ran Wilway farm with the help of unmarried Albert and her other sons and was often seen riding side-saddle on her way to visit family and friends.

Rose Crofskey Blake died in 1962 after a stroke three years earlier. Here she is, happily surrounded by family. If someone has a better copy of the photograph, or remembers the occasion, please get in touch with us through the link on the home page.

_______________

Rose’s younger brother John (Jack) Crofskey may not have produced the same kind of baked delicacies as his wife, sisters, or sisters-in-law, but his old Ford always generated a happy following of children when he and Jane visited the Ryans, or Joe and Barbara Crofskey. Their children knew that before he did anything else, he would fill a bowl with sweets or iced wafer biscuits.

It is not clear exactly what John Crofskey did between the time his mother remarried in 1885, when he was 11, and 1894 when he bought his first piece of land with Frank. His presence in the bush-felling photograph indicates that—like many Poles in the district—he cleared land and helped build the infrastructure of early Taranaki. The houses he built for himself and others reflected his building skills. He must have shown a maturity for Frank to transfer ownership of his part of the Midhirst property, and his stepfather doing the same with one of his properties when both older men moved to America.

After the fire destroyed Frank’s store next door, when John and Jane’s daughter Evelyn was two months old, the young family moved into a house that John built on his younger brother Joe’s Surrey Road farm, which John took over in 1901.

Evelyn with her parents, Jane (née Potroz) and John Crofskey.

Besides running the farm, John continued to buy and sell property in a counter-clockwise direction around Mount Taranaki (then Mount Egmont). Seven of his 13 children were apparently born at the Surrey Road farm. Several of his older children attended the Taitaramaika School when the family moved to Oakura on the northern coast. Another move was slightly inland to Lepperton and his last properties were in south Taranaki’s Pihama and Kaupokonui districts, heading towards Rose’s property in Waverley.

The first six Crofskey children. Back: Ethel (born 1897), Evelyn and Mary (born

1902).

Front: Joseph (born 1900), Bert (born 1898) and John junior (born 1896).

John bought 219 bush-covered acres in Kaupokonui five months after their oldest son, John junior, right, serving with the Wellington Regiment NZEF, was killed in action on 23 June 1917—seven days after being promoted to Lance-Corporal. According to his military records, he died either in France or Belgium and his body was “one of the many which were not found.” His name appears on the Messines Ridge New Zealand Memorial to the Missing in West-Vlaanderen, Belgium, and on New Zealand memorials in Pihama and Lepperton.33

The family story says that Jane strongly encouraged John to enlist. He joined the Wellington Infantry Battalion in August 1915. His records show five admittances to various hospitals for illnesses, such as measles “and its further complications” and two injuries, including one to the head. He re-joined his unit after each incident.

Less than a year after John junior died, his father sold the Kaupokonui property to his son-in-law, John Joseph Butler, who Evelyn married in 1915.

John Crofskey senior and Jane remained on their Pihama property. John kept six beehives. A cousin told John and Jane’s grandson Doug Crofskey of the day John died of heart failure following pneumonia in 1922: His bees swarmed and settled on the window of the bedroom where he lay, and on the day of his funeral, they followed his hearse to the old Midhirst cemetery more than 30 kilometres away—then disappeared.

Jane died three years later. She and her husband were both 48 when they died, and are buried together at the Midhirst Old cemetery.

_______________

As an adult who knew the value of education, Joe Crofskey—the 10-year-old who organised himself a job with schooling—leased two front rooms of his house to the Taranaki Education Board for use as the York Road School.

It was a matter of necessity. The nearest school was then an eight-kilometre walk to Waipuku. After Mary and Martin Ryan moved to Surrey Road, the cousins walked to school together. Their uncle John built a shelter half-way, so they had some protection from heavy rain. Irish Martin became the spokesperson for the settlers who were illiterate in English and petitioned for a school. The board bought land and, while waiting for it to be built, the local children continued to use Joe and Barbara’s home as their classroom.

Six Ryan and Crofskey cousins appeared in this York Road School photograph, circa 1917: In the back row, fifth from the left is Lill (Lillian) Ryan and third from the right is Joe's daughter, Helen Crofskey. In front of Lill is her brother, Fred, and to the right is Joe's son, Mick (Arthur) Crofskey. In front of Mick is his sister, Kit (Kathleen), sitting to the right of Mabel Ryan.

Mabel (Ryan) Autridge: “Girls and boys had a lot of fun to see who could jump across the puddles on the road without getting wet or muddy. Many failed and arrived at school with mud-spashed clothes and muddy boots.

“There was always a mad rush to try and clean up, before the bell rang, in the long grass in the school grounds—not always successful and some got a couple of straps for being so dirty and careless.

“One little boy, who lived on the Upper Surrey Road and had a long walk to school, used to arrive about 10am or later. There was scrub and bush patches all along the road and he used to go bird nesting and forget about the time. There were also large patches of blackberries, and when they were ripe, were a big temptation. The other children thought it a great joke, Victor arriving so late.

“When all was quiet in the schoolroom, we could see wekas in the bush… Once Mrs Balsom lost a valuable brooch, which she found after much searching in a weka’s nest, along with silver paper from cigarette packets, which had been thrown out after a euchre party. Mrs Balsom was a good teacher and taught the pupils word building and correct pronunciation.” (See Mabel Autridge's two reminiscent letters linked to this story.)

Helen (Crofskey) Meads kept this photograph of York Road School girls practising for one of the end-of-year concerts. If you are able to identify anyone, please get in touch with us through the link on our home page.

_______________

Sometimes circumstances forced pragmatic decisions regarding high school. When the Ryans bought a 100-acre farm in Sealy Road, Omata, the rest of the family moved there leaving Frederick—who had been attending Stratford High School—in charge of the Surrey Road farm.

Pat: “When they found out he had to leave, some representatives from the school actually came to visit grandmother… right up Surrey Road under the mountain to plead for him to stay at school. Grandmother told them someone had to do the work [on the farm]… she had another farm needing clearing…

“My aunty Lill told me the move was quite something:

“A pile of stuff was taken by a dray pulled by a horse but everyone—all the children—had things to carry. They shifted by train. When they got off at the train station they walked to Omata, down Sealy Road to the farm. Aunty Lill said it was a very hot dusty day and here they were carrying bits of furniture and all sorts of stuff in a long line walking to the farm.”

Lillian Francis Ryan with her baby sister, Myra May, the family's last-born, who was six when Lillian married Des Raill.

At Omata, the Ryans saw gorse for the first time. It covered the new farm’s entire 100 acres. They admired it—at first. The family book mentions a meat safe as their “one luxury.”

Pat: “They left my father on the [Surrey Road] farm. The previous year he had rheumatic fever. He was very, very ill… He was 16 when they left him on this 200-acre farm with no fences, a lot of bush needing draining, very few implements, a few cows to milk by hand, and a dog.

“If he wished, he was allowed to get flour, sugar, tea and a few other essentials from the Midhirst Dairy Company store but if he wanted meat he ate native pigeons, tickled trout, or chopped wood to sell to buy the meat. He baked his own bread and said if we went up to a certain spot in the creek near the house we would find the first batch of bread he made—solid as a rock.”

_______________

It was one thing to buy land, quite another to have enough income to turn it into a viable concern. Joe Crofskey appreciated that he could not do it alone. In 1899, at 20, he married 17-year-old Barbara Stachurska and bought a farm on Surrey Road.

Their granddaughter, Shona Spelman, explained in the family book that their initial income came through Joe’s working at the York Road quarry eight hours a day and Barbara’s milking their cows. Both spent any spare time clearing bush—often past midnight. Barbara once left their first two children, Annie, and Joe junior, at the house while she fetched the cows from the bush—then became lost. Frantic, she managed to find her way out by following a stream. It is not mentioned in the book whether the cows followed her.

By the time Joe and Barbara moved to York Road in 1911, they had six children—an incentive for offering the temporary classrooms in their home.

While they were still living in York Road near the Ryans, Joe and Barbara would see Mary returning from the races in a horse-drawn gig holding up her fingers to indicate how much money she had won. According to the family book, she dreamt of horses winning and often won a subsequent bet.

“One day Joe and Barbara, being hard up, decided to join her. The thought of using Mary’s good luck to help their finances was irresistible… That day there wasn’t one pay out!”

Mary Ryan continued to attend race meetings. Here she is at the New Plymouth racecourse with her son Dave (in striped blazer), his wife, Molly, and their children. The couple on the left is unnamed.

Annie, Joe and Barbara’s oldest child, died from spinal meningitis in 1913 at 13. Barbara was hospitalised with pneumonia at the time. Family remembered Annie’s coffin in the glass-sided coach pulled by two black horses and Barbara attending the funeral, hardly able to walk.

Annie stands behind the infant Mary Rose Ryan, who as a six-year-old shared a grave with her grandmother Franciszka. Nell (Ellen) Blake is standing behind David Ryan, born in 1901.

Joe and Barbara’s tenth child, Elsie, was born at the York Road house a week before most of the family moved to their Lepperton farm in 1920. The two eldest boys, Joe junior and Mick (Arthur) ran the old farm while the rest of the family set about breaking in the new one.

After butterfat prices dropped by 80 percent (from 2/6d to 6d a pound), Joe bought pigs to sustain the family, and buttermilk from the Lepperton milk factory to sustain the pigs. They survived the 1930s Great Depression by Joe’s becoming a city dairy supplier and Barbara’s selling eggs and cleaning for neighbours at a shilling an hour.

Joe and Barbara Crofskey recorded their 50th wedding anniversary with their children. Back row from left: Joe junior, Mick, Ben, Bill and Frank. Front from left: Kitty Grant, Helen Meads, Verne McCabe and Elsie Crofskey.

Joe and Barbara retired to Waitara in 1952 and their son Ben became sharemilker on their farm. Joe died at 88 and Barbara at 94. They are buried together at the Waitara cemetery.

_______________

Martin Ryan died of cancer in Omata on 14 November 1930, aged 65. Mary continued to establish her four sons on farms. She became as much of a force in the community as her older sister Rose.

The family book tells how many factory milk producers withdrew in the early 1930s, when a few suppliers for the Royal Oak Cheese Factory pioneered New Plymouth’s Milk in Schools and Hospitals scheme. Those who remained, persuaded Mary to stand as a director. When she met incumbent MP of New Plymouth, Frederick Frost, she negotiated a fairer price for their milk.

Pat: “While she was a director, she persuaded the board that New Plymouth would become a city one day and they needed to get in on the ground floor to provide city milk supply. A lot of them laughed. Some left the company when it became a fact but… those farmers [who stayed] became better off because they did what she had suggested.”

Pat’s fondest memories of her own life on their farm are linked with the Old English sheepdog who extracted the cows, one by one, from all over the farm and bush for her father to milk.

“Woolly was my best friend. I lived with that dog. He guarded me. He told on me on one occasion… I would have been about three. We had ducklings and it must have been a cold day because I decided that it was too cold for them. I got a pie dish and took these ducklings, with Woolly accompanying me, to where there was a patch of very tall pines and all the needles on the ground. I buried the ducklings under the pie dish and covered it with pine needles to keep them warm.

“And that dog went and told mum, went and kept at her until she said, ‘All right, Woolly, what is it?’ And he took her over to the pine needles and she rescued the ducklings.

“Gran was in her 80s when she said to me, ‘Pat, I’ve decided to retire. I’ve bought a little cottage in Waitara.’ Great-uncle Joe had retired and was living in Waitara and they’d always been great friends.”

And so Mary, pictured here with her 80th birthday cake, stopped moving from family to family, helping with babies and children and farms, and bought a property where the house “was looked after very well indeed but the garden was a jungle.”

“One thing my grandmother did wherever she lived, she created a park—not a garden, but something beautiful. In no time that section was reduced to order by someone in their eighties. She planted it and everything was lovely.”

Mary Crofskey Ryan died in 1965 and is buried with her husband Martin in the Waireka cemetery, Omata.

_______________

One of Pat’s most treasured possessions is a glass candlestick, right, that she was told by her Aunt Lill was in her great-grandparents’ luggage on the fritz reuter in 1876. Lillian gave it to a Polish friend, who when she downsized, returned it to Pat.

Several Kurowski-Crofskey descendants have made trips to the now-named Jackson Bay. Pat, in early 2000, was determined to see the Arawata cemetery—and did.

“I could see the plaque but the cemetery was all but ruined, gone because of the climate and no one attending to it. While I was going back up the West Coast I called in to every possible place where I thought they might be able to do something about it, including [former] MP for the West Coast, Damien O’Connor, whose secretary took details to give to someone who she said was trying to restore it. I never heard if anything happened.

“All the way, I could see my great-grandfather’s name always spelt incorrectly. In my ignorant way, with a red pen I crossed it out and wrote the correct spelling at the top. Several years later Sandra said she could follow me all the way up the West Coast.

“No one stopped me [writing on the plaques]. They watched me, they didn’t stop me.”

Sandra remembers planning her trip for autumn, when sandflies tend to be less prolific.

“We were warned about them. When you get out of the car you must smother yourself with insect repellent. It wasn’t wintertime but it wasn’t particularly warm. The sea wasn’t particularly rough. I wanted to walk to where there might have been a settlement because I was told by someone else in the family that there was no trace of anything because nothing lasts in the very extreme wet weather.

“We had to hold on to a rope and pull ourselves up quite a steep bank to get to the start of the track, across the road from the beach at Jackson’s Bay.

“We walked for about 15 minutes following a stream, only a drain really, a trickle, until we came to a river. The trees are that close together you can’t get through them… You don’t go off the track—you would be lost. You can’t see the sky, the canopy is right over you.

“It was beautiful, but all the ground is sandy because it floods. I don’t know how they could have grown anything, but apparently they did clear it and they did make some sort of huts. They were given these bits of land but they had nothing, nothing to make a living out of. They didn’t have a jetty or anything. That’s why Franciszek got in a boat and went to do some prospecting.”

Jackson Bay today is still at the end of the West Coast Road. There are a few houses, used by fishers and whitebaiters, and Sandra recalls the “wonderful” fish and chips served from an old train carriage.

She saw no trace of Polish settlement but did find some records in Haast and in Hokitika’s archival library that, like Pat, she wanted to correct.

“I was watched very carefully and handed a pencil. I was told I could not cross out anything but could write my interpretations beside the record.

“I was told the official policy is that they are the official records of the time and even though they may be incorrect, they must be retained in that format. Whatever else is done is seen as another version. They can’t be permanently corrected no matter how much proof we come up with.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2017

Updated November 2022

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS, APART FROM THE OLD MIDHIRST CEMETERY AND THE FINAL ONE, COME FROM CROFSKEY FAMILY COLLECTIONS

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - These are the words Mabel Autridge (née Ryan) used to describe her mother, Mary Ryan (née Crofskey) to her niece, Sandra Singleton.

- 2 - See story jackson's bay 1874–1979 on this page.

- 3 - From a statement made at Big Bay by Henry Fisher and JL Gunn to the Commissioner of Police, Dunedin, dated 18 June 1878. Several newspapers of the time used their statement. Other quotes are specified more fully later in the story, see below for newspaper titles, all through Papers Past, and the National Library of New Zealand.

- 4 - This conjecture from Lake Wakatip Mail, 25 July 1878, page 2, UNTITLED.

- 5 - Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1877, D–1, New Zealand, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND (LETTERS TO THE AGENT-GENERAL) page 3, item 3.

- 6 - Ibid, page 4, item 6.

- 7 - AJHR, 1879, H–9A, New Zealand, JACKSON’S BAY COMMISSION (MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS, EVIDENCE, CORRESPONDENCE ETC. IN CONNECTION WITH THE), page 81.

- 8 - Ibid.

- 9 - Ibid, page 77.

- 10 - Ibid, page 21.

- 11 - Ibid, page 30.

- 12 - AJHR, 1879, H–9B, New Zealand, JACKSON'S BAY SETTLEMENT (STATEMENT SHOWING IN DETAIL THE AMOUNT

PAID TO EACH SETTLER FOR LABOUR EACH MONTH DURING THE YEARS 1875, 1876, 1877 AND 1878.), pages 7, 8, 13 and 15. (pages 9 to

12 are missing.)

- The commission's summary: AJHR, 1879, H–9A, New Zealand, JACKSON’S BAY COMMISSION (MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS, EVIDENCE, CORRESPONDENCE ETC. IN CONNECTION WITH THE), page 60. - 13 - Ibid, page 60.

- 14 - Timaru Herald, 25 July 1878, page 3, THE FATAL BOAT ACCIDENT AT BIG BAY, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 15 - Timaru Herald, 22 July 1878, page 2, BOAT ACCIDENT AND LOSS OF LIFE AT BIG BAY, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 16 - Lake Wakatip Mail, 25 July 1878, page 2, UNTITLED, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 17 - West Coast Times, 19 July 1878, page 2, FRIDAY, JULY 19, 1878, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 18 - Southland Times, 19 July 1878, page 2, UNTITLED, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 19 - Westport Times, 30 July 1878, page 4, THE DISASTER AT BIG BAY [WEST COAST TIMES], Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 20 - Otago Witness, 27 July 1878, page 8, BOAT ACCIDENT AND LOSS OF LIFE AT BIG BAY, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 21 - From the Arawata Pioneer Cemetery record: “YELL, Jeremiah, died soon after arrival in March 1875.” I sourced this from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists’ Research Centre, 159 Queens Road, Panmure, Auckland.

- 22 - AJHR, 1878, D–6A, New Zealand, JACKSON'S BAY SPECIAL SETTLEMENT (FURTHER PAPERS RELATING TO), page 5.

- 23 - Thanks to Florinda Lambert's original research.

- 24 - Ibid.

- 25 - Contact Sandra at sndrsngltn6@gmail.com.

- 26 - The CD New Zealand Marriages 1836-1956 is available from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists Inc through www.genealogy.org.nz/.

- 27 - Excerpts from The Kurowski Family in New Zealand 1876–1990.

- 28 - This particular story from the Wanganui Herald, 28 March 1895, page 3, from Papers

Past, through the National Library of New Zealand,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WH18950328.2.27 - 29 - Photograph of Franciszka Crofskey's stone and Frances Schnell's headstone by Sandra Singleton,

2009;

Photograph of old Midhurst cemetery by Barbara Scrivens, 2013. - 30 - This excerpt from the Kurowski family book by Rose and Ernest Blake's granddaughter Irene Smillie, born 1914, she died in 2004.

- 31 - This excerpt from the book contributed by Joe and Barbara Crofskey’s granddaughter Shona Spelman.

- 32 - Ibid, Kurowski family book, from page 116.

- 33 - John Crofskey shares his date of death with 42 others from the NZEF, and is among 22 whose names appear

on the Messines Ridge Memorial to the Missing. The three relevant pages from the Commonwealth War Grave Commission

website:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead.aspx?cpage=1

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead.aspx?cpage=2

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead.aspx?cpage=3