The Possenniskie Family

When brothers Ian and Barry Possenniskie found the book, history of the polish settlers in new zealand by JW Pobóg-Jaworowski,1 in the late 1990s, they expected to see their family represented.

They had read the notes that their aunt Marjorie (née Possenniskie) Lincoln had collected about the family, and knew that their great-grandfather, William Possenniskie, had arrived in Auckland in 1847.

The book mentioned Jan Rajnold and Jan Jerzy Forster, the father and son naturalists who accompanied Captain Cook on his second voyage to New Zealand between 1772 and 1775. It mentioned Edmund Strzelecki, who arrived in Sydney in 1839 after spending three months in New Zealand. It mentioned a sailor who arrived on a whaling ship in 1854, who was nameless but had Poland recorded as his place of birth. It mentioned Samuel Edward Schrimski, who arrived in 1861, and became Oamaru’s mayor before becoming an MP.

The brothers were puzzled by a mention of an unrelated Henry Louis Possenniskie, tailor, who was born in Warsaw in 1842 and who had arrived in Auckland in 1861. Pobóg-Jaworowski took his information about him from an entry in the cyclopedia of new zealand.2

Pobóg-Jaworowski’s book contradicted Marjorie Lincoln’s notes and stories. The brothers decided it would be prudent not to interrogate and possibly upset their then aging aunt by suggesting something may be amiss, but Barry nagged his more history-minded brother to untangle the family’s real story.

A hip-replacement that went wrong gave Ian the time to investigate. With “nothing to do” for three months while waiting for his leg in plaster to heal, Ian combed through the existing records.

Then, global search engines were in their infancy, and Ian’s primary sources lay within the Births, Marriages, and Deaths offices in Lower Hutt. His wife, Christine, used to drive him there, or to the Wellington archives, or the Wellington library, which held census information and other records. After hundreds of hours’ research, in 2001, he compiled a William Possenniskie timeline and printed a book, which he distributed to his family, the National Library, the Polish Embassy in Wellington, and various Polish associations in New Zealand.

Ian’s Aunt Marjorie knew nothing of his research until she received his book. In the end, although her stories did not show a complete picture of the family, they did ring true.

Ray Watembach gave me the Polish Genealogical Society’s copy of Ian’s book last November. With far more easily accessible digital information nowadays, I have been able to add to his original information. I made extensive use of Papers Past—the digitisation arm of the National Library of New Zealand—which enriched several aspects of the story.

Many thanks to Ian. I appreciate his tenacity for getting to the bottom of something in his family background that niggled, and his generosity and input.

Here is the story of the first Polish family to grow up in New Zealand.

—Basia Scrivens

NEW ZEALAND’S EARLIEST POLISH FAMILY

by Barbara Scrivens

One could be anyone and anything in 1847 Auckland, the capital and commercial hub of colonial New Zealand.

One of the men who arrived in Auckland in 1847, who later wrote under the pseudonym “An Old Hand,” described Auckland as a place with few houses or buildings, where fresh water had to be drawn from wells, where oil lamps provided night light, and where the wooden wharf could support only small boats, which at high tide, could reach the bakery on Wyndam Street.3

Māori supplied the growing number of European visitors with fresh fruit and vegetables. There was no regular or direct route from England to New Zealand. Anyone arriving in Auckland went first to Australia, usually Sydney, on ships that spent up to five months at sea, then had to wait for a cargo vessel with space for human passengers.

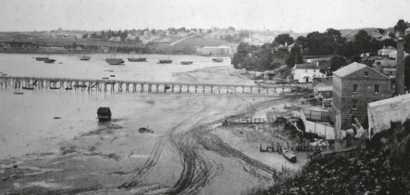

The Auckland waterfront in the 1850s. James D Richardson took this photograph facing east from Point Britomart.4

“An Old Hand,” wrote about the “outrageous prices” and mark-ups, and how easy it was for “those who were enabled to obtain merchandize from home to make fortunes, and those who sent the goods still larger ones…”5

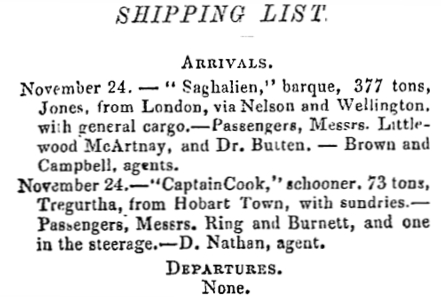

According to his own declaration, William Possenniskie arrived in November 1847, the same month as the ships saghalien and captain cook, which carried cargo from London.

As soon as the ships berthed, local merchants started selling their contents. Off the saghalien, which had already been to Nelson and Wellington, Brown & Campbell advertised goods such as champagne, rum, stout, “strong pale ale,” cases of itemised books, blankets, shirts, and “chintz handkerchiefs.” Gibson & Mitchell offered “Ivory, Black and Stag Handled Table Cutlery,” as well as more practical items such as horse rasps, sail twine and needles, “Moleskin, and Duck Trowsers [sic],” white vinegar, and Edam cheese.6

The captain cook left cigars, tobacco, snuff, and baskets, as well as jewellery, bonnets, braiding, ginghams, and groceries such as preserves, raisins, almonds, and “fine Mauritius or Java” sugar, in a loaf, or crushed.7

Cargo ships to New Zealand then carried few passengers. Newspapers generally only printed the passenger lists of those in cabins and did not tend to mention those who travelled “steerage.”

There is no mention of a Possenniskie—or any possible misspelling of his name—on any ship that arrived in New Zealand in 1847. On 14 October that year, the saghalien from London docked in Wellington with 10 unnamed steerage passengers, but according to the Auckland newspapers, none arrived in Auckland, so perhaps William Possenniskie had stopped off in Hobart and was the single unnamed steerage passenger mentioned by the daily southern cross off the captain cook:8

“An Old Hand” wrote of anchoring off the Devonport wharf when he arrived in late 1847. Passengers had to raise a flag to summon a boat from Auckland to get to the shore on the other side.

… We landed at a little wooden wharf, about where the Custom House now stands. Plenty of natives were to be seen, attired only in a blanket, and I recollect being astonished at their physique and the ease with which one of them shouldered my box and carried it into a friend's store for a very trifling payment.

The main business street was Shortland Crescent, now called Shortland Street, and the building known as Brown and Campbell’s store was then in course of erection. The main entrance from the harbour was up a private lane owned by Messrs. Williamson and Crummer, at one corner of which stood the Victoria Hotel…

Queen Street was almost unbuilt upon, and there were scarcely any buildings beyond Wyndham Street, at the corner of which stood the bakery of Mr. Goodfellow. A boat could at high tide be taken up to this store… The rotten planks which covered the creek [gave] way. I did not fall through, for, if I had, I should certainly have been washed out to sea, as it was a stormy, rainy night, and there were no persons about. Fortunately, the hole was not big enough to take my arms through. I got a great shock, but I remember I thought that better than stopping in a big auction store all night with legions of rats.

The Maoris used to sing and chant half the night through in their tents and boats on the beach opposite. The townspeople depended mainly on the natives for their supply of potatoes, onions, fish, fruit, &c., and these things were very cheap indeed. I have a lively recollection of my first venture in a good feed of peaches. [I] purchased a large kit for sixpence—holding probably near fifty; I had rarely seen them under sixpence each at home—I took them to my room, and, in spite of my landlady's advice to be careful in not eating too many, I polished off the lot!9

LEFT: In 1860, a view from the Smale's Point in Auckland looking towards Devonport.10

The rosetta joseph arrived in Auckland a week after the saghalien. Its cargo apparently included tea that it had picked up during the voyage from England, and 75 sheep.11 The new zealander published the names of her 30 passengers in its inner pages a few days after her cargo had been announced on the front pages. On board were a Mr, Mrs, and a Miss MA Rawson.12

William Possiniskie [spelling on the marriage certificate] and Mary Anne Rawson married at St Paul’s church in Auckland on 1 June 1848. The speed of this marriage, just six months after they arrived in New Zealand, suggests the couple may have known each other in London. The Rawsons may have been confirmed as travelling on the rosetta joseph, but the casual nature of the passenger list did not give any hint of where they came from, where they embarked, or whether William may have been aboard in the steerage section at the same time.

New Zealand marriage certificates in those days did not include the birthplaces of the bride and groom, or their parent’s names, so the generic Mr and Mrs Rawson, too, melted into the early Auckland population. There is a probability that the Mary Ann Rawson, “beloved wife of John Rawson of Wyndham Street” who died aged 68 in 1859, was Mrs Rawson.13

The registrar of William’s and Mary Anne’s marriage misspelt the bridegroom’s surname—and possibly the bride’s given name—but their great-grandson, Ian Possenniskie, doubts that the surname is in any case correct.

According to family story, William Possenniskie left Poland aged 17 to escape conscription. William said he was born in Warsaw in 1819, and by the time he was 17, that part of Poland had barely survived the 1833 November Uprising.

Despite Poland’s being partitioned for the third time in 1795 by its three imperial neighbours—Prussia, Russia, and Austro-Hungary—in 1809, a core Duchy of Warsaw clung onto its Polish heritage, thanks to Napoleon’s needing a military outpost in central Europe. Around 200,000 Polish Legions fought in the Napoleonic Wars on the French side and lost many tens of thousands of men.14 After the French defeat in Belgium in 1815 to an allied army of troops from Britain, Prussia, and the Netherlands, the Treaty of Vienna redrew the Duchy’s boundaries. It lost land to Prussia, Russia, and Austria, and became known as the Congress Kingdom. Poznań found itself within Prussian-partitioned Poland, and became known as Posen.15

Ian Possenniskie believes that his surname gives an inkling of his great-grandfather’s origins. The only other pieces of background information on William Possenniskie come from his own written declaration on his naturalisation statement that he was born in Warsaw, and that he was 28 in 1847.16 That would have meant that he left his Polish home in 1836, and that aged 17, he faced imminent recruitment into the Prussian army, with its strict and lengthy conscription system. Instead, he went to London, where he trained as a tailor.

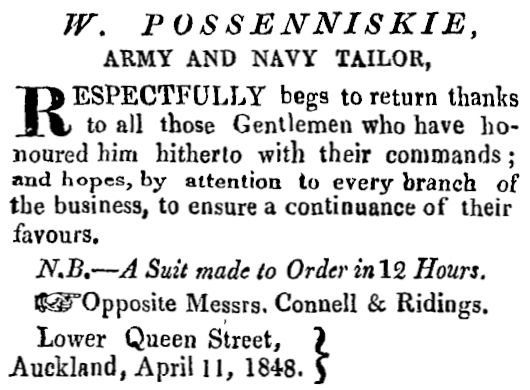

One could be anyone or anything in 1847 Auckland, but a trade like tailoring could not be faked, and every trader needed to keep his customers. William lost no time organising his business—targeting the troops of retired soldiers that governors George Grey and Robert Fitzroy requested be sent from England. The soldiers were to serve as the Royal New Zealand Fencibles for seven years, and ‘protect’ the early Auckland settlers. They and their families settled in Howick, Onehunga, Otahuhu, and Panmure.

Patrick Hogan painted this 1852 image of Auckland from Smale’s Point. Dr Thomson W Leys gifted it to the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki in 1915.17

The fourth of 10 Fencible ships, the sir george seymour arrived in Auckland from Gravesend just two days after the saghalien and the captain cook, and there is no doubt that William would have noticed some of the 77 soldiers who arrived with her, and the other military personnel already in the city. “An Old Hand” spoke of regular night bugles and fire alarm drills, sentinels around the barrack walls, and troops and bands marching to church on Sundays.18

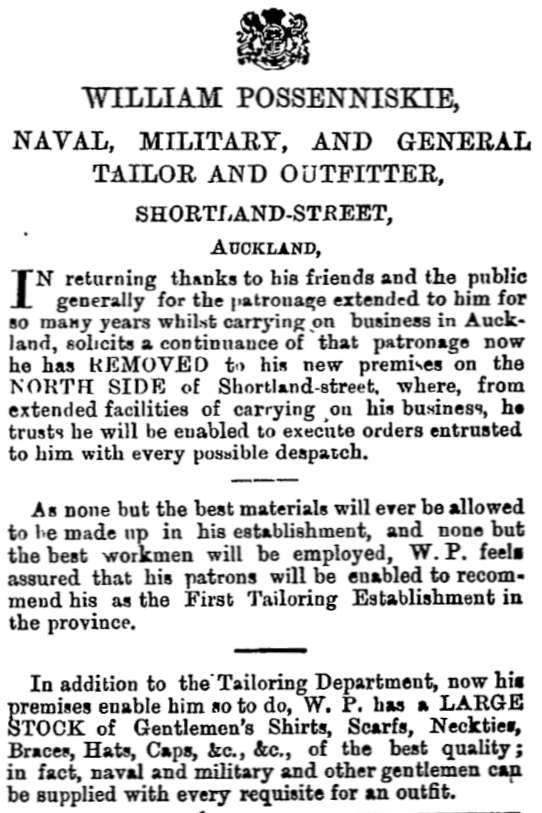

William started advertising in Auckland newspapers in April 1848:19

By October 1851, William and Mary Anne had had two children: Edward, in March 1849 and Louisa, in January 1851.

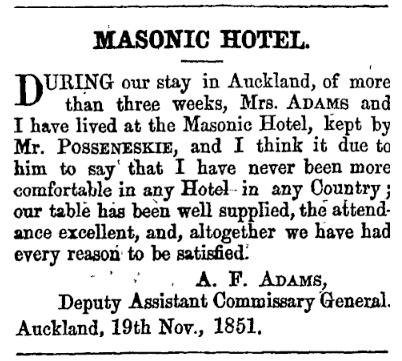

By then, William had taken over the Masonic Hotel in Princes Street. He informed the “Inhabitants of Auckland and its vicinity” that “in consequence of his becoming the Proprietor of the Masonic Hotel,” he had given up his tailoring business in Shortland Street to a certain Thomas Lundergan.20

There is no doubt that William Possenniskie made a name for himself within early Auckland society, and that he was a hospitable and popular host. His Masonic Hotel held many a social gathering, including the annual dinner of the Sons of St Andrew just months into his proprietorship.21

This advertisement appeared in both the city’s newspapers, the daily southern cross

and the new zealander:22

William also promoted the soups that the Masonic Hotel had been offering during the winters before he bought it. Like

at the Caledonia Hotel in Fort Street, the Masonic’s soups were available from 11 in the morning to four in the afternoon,

and were popular with the single men at a time when there were few women to take on roles as domestic servants and cooks,

and when there were no restaurants.23 More from “An Old Hand:” Before 1850 everything in Auckland was in a very primeval state—no free libraries for

young men, no regular amusement except the billiard-room or the hotel. Very little sociability existed, but food was

cheap, and people were easily satisfied. In 1850 native produce was very cheap, as much fish as you could well carry for 6d., and

potatoes, onions, peaches, Cape gooseberries were a drug. The natives were very friendly with the settlers, and wars, I

believe, would never have arisen but for the land quarrels with the Government. The natives were always very stolid, and

rarely expressed wonder at the Europeans' work… The natives soon lost all their innocence and were apt pupils of the roguish elements in

the Europeans.24 William Possenniskie anticipated the needs of the growing colony: by 1853, he had fitted the Masonic Hotel with

“spacious bathrooms” where Aucklanders could take “hot or tepid baths” at any

hour.25 Three months after taking over the Masonic Hotel, William Possenniskie applied for naturalisation. On a letter written from the Masonic Hotel in Auckland, and dated 10 December 1851, William Possenniskie addressed

“Her Colonial Secretary” in New Zealand, “requesting naturalisation:” I do myself the honour to request that you will submit my application to His Excellency the

Lieutenant Governor that I may have letters of Naturalisation granted to me. I am native of Warsaw in Poland, age 32 and I

arrived in this Country in November 1847. I beg to state that I married a British Subject in 1848 and I have two Children

– Edward and Louisa and I shall feel obliged if it should be necessary that their names should be included in the

letters of Naturalisation. I have the honour to be – Sir – Your Obedient Servant – Wm

Possenniskie. He was awarded early naturalisation on that date. The wellington independent carried

the Governor-in-Chief, Sir George Grey’s official “proclamation” that he deemed William to be a “natural born

subject of Her Majesty.26” Ian is not certain that his great-grandfather wrote the naturalisation application: “He appears to have signed it himself, but the letters are hard to distinguish. On the other hand, it was normal

at the time to obtain a scribe to prepare an important document such as this and that scribe may have been writing down

the name as he heard it.” William and Mary Anne had another five children. Birth registering officials in Auckland spelt their seven children’s

surnames six different ways: Already, Edward had been registered as Possiniski, and Louisa as Possiniskey, with their

father recorded as a tailor. Mary Anne [Eustina] Posseniskie [sic] was born in 1853. Her father was recorded as a hotel keeper. Rosanna, born in

1858, was the only one whose official birth records match the official family spelling. Helena Possenwiskie [sic] was born

on 22 February 1860. By the time William junior Posseneskie [sic] was born on 5 May 1863, his father was again

recorded as a tailor. Frederick Harry [Henry] Posseniskie [sic] was born in April 1865. William’s name started appearing on Auckland’s jury lists from 1849, when the family lived on Princes Street and when

his “trade or calling” was “tailor.” The jury lists for the next 10 years suggest that he ran

several hotels and tailoring outlets. In Otahuhu, in 1856, the jury list has him down as a “hotel keeper,” but

in Goal Street a year later, he is again a “tailor.” In Newmarket, in 1858, he is an “innkeeper,”

but in Parnell, in 1859, again a “tailor.”27 By 1859, William seems to have focused again on tailoring. It is not clear whether he kept the Masonic, or his other

hotel establishments, but he took over another tailoring business in Shortland Street that November.28 By 1866,

he had moved to larger premises in the same street:29 The world turned for William on 22 November 1871, when his wife died aged 43, of pulmonary consumption (tuberculosis),

then a long-lingering disease with little hope of recovery. Edward was 22; Louisa, nearly 21; Mary Anne Eustina, barely

18; Rosanna, 13; Helena, 11; William junior, eight; and Frederick Henry, six. Mary Ann Rawson Possenniskie lived long enough to see her namesake marry a navigational lieutenant in the Royal Navy,

George Edward Gresley Jackson, at the Possenniskie home in Shortland Crescent on 16 October 1871. Edward and Louisa

stood as witnesses. The bridegroom’s third name has made it possible to match him to an entry in the captains register of Lloyds of London,

which says that he was born in Newcastle in 1840,30 and that he died in San Francisco in 1907. A classified advertisement in the hour of London shows that Louisa, “eldest

daughter of William Possenniskie of Auckland,” married Edward Francis Gray, second son of the late George Gray of

Berkshire, England. The ceremony took place at the parish church in Reigate, Surrey, on 29 December 1873. A death registration for a Louisa Gray shows that she was 33 when she died in 1883 in Kensington, London. Without a

specific death certificate, it is impossible to be sure this was the Possenniskie’s eldest daughter, but the ages

match. William Posseniskie [spelling on the marriage certificate] senior married 39-year-old widowed hotel keeper Grace

Chapman on 23 September 1873, at the Auckland Registrar’s offices. She was apparently born in Cornwall, England. According

to a relative of hers, William was her fourth husband. Family speculation was that William married Grace in the hope that she would help him care for his young family, but

the self-supporting and strong-willed Grace quickly quashed that hope. Ian believes that his great-grandfather became even

more unhappy after the marriage, and that that unhappiness drove him to leave Grace, and Auckland, and move with Edward

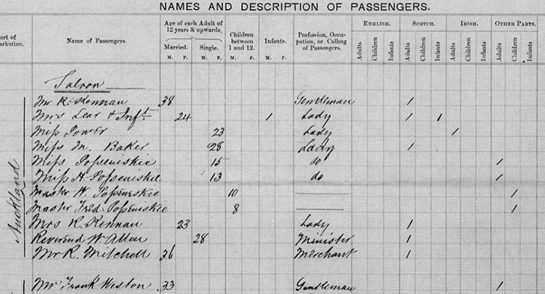

and his four youngest children to Australia. The four children appear as saloon passengers on the hero bound for Melbourne via

Sydney on 29 January 1874. They travelled with their mother’s cousin, 28-year-old Mary Baker, who had taken over the

child-minding and house-keeping. Rosanna and Helena, aged 15 and 13, are classified with Mary as adult ladies: It is not

clear whether they disembarked in Sydney, or Melbourne, or whether their father sent them ahead, or called for them after

he had himself settled. A section of the January 1874 list for the

hero. In the months before he married Grace, William seemed to be continuing his businesses and getting on with life in

Auckland. With fewer military customers, he expanded his civilian range, was advertising for “good journeymen

tailors,”31 and may have thought of expanding into Franklin.32 His last

advertisement—for a lost black and tan terrier—appeared in May 1873. The tone of advertisements bearing his name took on an uncharacteristic, light-hearted nature in October 1874, which

suggests that he had left the city by then. One was a poem that ran several times, about how a young man “won his

bride” after he was fitted out by Possenniskie the tailor.33 The irreverent and breezy tone of the

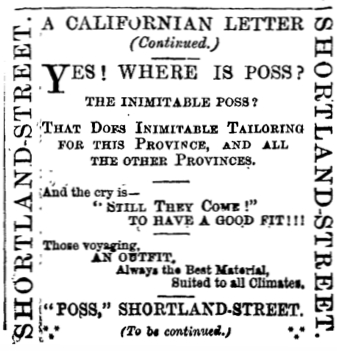

advertisement was completely out of character for a man of William’s elegance, and one still mourning his first wife. The new zealand herald had a special correspondent in San Francisco, who must have

been a customer of William’s when he visited Auckland. Under the headline Our Californian Letter, on

30 March 1875, he mused: … Where is Poss? the inimitable Poss., he of the German moustache and French

imperial, that used to strike terror into the hearts of delinquent patrons? Where is the faithful friend of the

impecunious youth of Auckland, the hope and stay of the upper crust Volunteers, and the pillar of the colonial army of

hard up?…34 Someone as well-known and well-respected within Auckland’s still small community as William Possenniskie could not have

still been in the city and not be found. Without an answer to his preferred tailor’s whereabouts, the correspondent

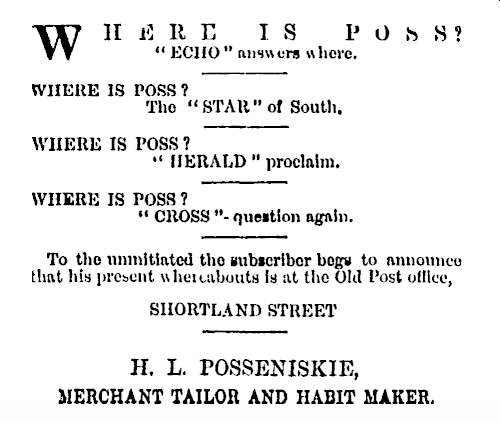

proposed other Auckland tailors that his readers could use. Almost immediately, advertisements like this started to appear:35 And, as if to answer the question to that advertisement, a certain HL Possenniskie, “merchant tailor and habit

maker,” announced that “his present whereabouts is at the Old Post-office in Shortland

Street.”36 Perhaps William’s Auckland customers believed that HL Possenniskie was a relative whom the older man had trained.

According to the cyclopedia of new zealand, auckland provincial district, Henry Louis

Possenniskie had “been established” as a tailor in Auckland since 1864. Coincidentally, he also said that he was

born in Warsaw, and left aged 17. He said he was born in 1842, and had “learnt his business in his native

land.” He also went to London, where he was “engaged in his trade,” and arrived in Auckland on

31 August 1864 aboard the portland.37 There was no passenger named Henry Louis Possenniskie aboard the portland on that

voyage, which left from London on 28 May 1864. In its “Shipping Intelligence” for that ship, the

new zealander lists a George, Anne, and Jane Poyner, and a Harris

Posner.38 It is not clear how much of the tailoring business Henry Louis would have learnt in Warsaw by the time he was 17. It is

also not clear why, if he had started his own business under the name Henry Louis Possenniskie in Auckland in 1864, there

seemed to have been no advertising for his shop. Ian believes that “Harris Posner” worked for William when the younger man arrived in Auckland. It would not

have taken much for a Pole just arrived in a new city to investigate a shop with a Polish-sounding name, especially if

that was one’s own trade. In the 1867 wises directory of businesses in Auckland, Ian

found only William listed as a tailor in Shortland Street. It took until 1872 for Henry Louis Possenniskie to be listed

separately as a tailor in Wellesley Street, and that was as a manager of William’s shop.39 Ian: “The Posner who arrived on the portland in 1864 simply

disappeared… As an alien, he would have been unable to vote until he was naturalised, there would have been very

little evidence of his early years. I have looked up records for 50 years [from 1864], and there are no marriages, births,

or deaths for Posner, nor does the name appear on electoral rolls or directories. This would tend to confirm a name

change.” Based on the evidence he collected, Ian concluded that Henry Louis Posner took over William Possenniskie’s business

after William departed for Australia, changed his name to Possenniskie and, indirectly, assumed the older man’s identity

to retain his goodwill. A Henry Louis Possenniskie, occupation tailor, did appear on the naturalisation records on

1 December 1882, several years after William had left New Zealand.40 In 1874, William would have been 55, Edward 25, and his four youngest children were between eight and 15. Even

with Edward’s help, this would have put a significant burden on a man possibly too old to get employment that paid enough

to support them all—and their housekeeper Mary Baker. By selling his Auckland business to his former employee,

William would have been able to raise the capital he needed to maintain the household in Australia. Ian’s research led him to several of Henry Louis Possenniskie’s (Harris Posner’s?) descendants in Auckland, who were

surprised of his existence, and unaware of any of the story entangling their ancestor with Ian’s. Henry Louis had no

living male descendants, and they had thought the Possenniskie name had died out. It is not clear whether the young man Harris Posner decided to reinvent himself as Henry Louis Possenniskie on impulse

after he saw the 30 March 1875 article in the new zealand herald because he thought it

would challenge his business, or whether it was a calculated move. The cyclopedia entry

appeared after his eldest son died in 1893, which suggests that he lived with the story he had created around himself, and

died with its secrets. _______________ Marjorie Lincoln believed that Mary Ann Eustina Possenniskie left New Zealand soon after she married, but there were

five Jackson children born in New Zealand between that marriage and 1878: Florence Gresley, who died aged 13 months in

1872; George William Gresley, who was born in September 1872; Edward Nigel Gresley, who was born in December 1874; Francis

Lionel Gresley, who was born in 1876; and an unnamed child who was a year old in 1878. In a 1952 newspaper interview in Honolulu, Edward Nigel Gresley Jackson said that his family moved there from New

Zealand when he was four, so the Jackson family would have been in Auckland in 1878—well after William and at least

his younger four children had left. Articles in the daily southern cross support the story: In January 1872, the

newspaper wrote of a Lieutenant Jackson of the Royal Navy, and formerly off the virago,

involved in the establishment of a school at Fort Britomart, and that he intended to give the boys under his care

“practical instruction by taking measurement of various objects, and thus making the study thoroughly

interesting.”41 The previous July, hms virago had been among 21 “vessels of war” that

were then “on their passage home for the purposes of being put out of commission and their crew paid

off.”42 A photograph of British Naval Lieitenant George Edward Gresley Jackson, which appeared in a

Hawaiian newspaper. A few weeks after the mention of the new school, Lieutenant G Jackson’s name appeared in another capacity: he was

elected commander and gunnery instructor for a new Naval Brigade in Auckland.43 By April 1872, the Britomart Collegiate School for boys had opened, with Lieutenant Jackson, RN, as “Mathematical

Instructor (marine and field practice).”44 It is not clear exactly when the family moved to Hawai’i. Eustina appears without her husband on a passenger list dated

28 October 1878, travelling on the rms zealandia with four children aged five,

four, two, and one. Her husband was master of the vessel storm bird, which arrived in Honolulu on

5 October 1879 with 71 adults and 22 children. Its passenger list is so illegible that it is impossible to

know whether Eustina and the children travelled with him. At least three more Jackson children were born in Hawai’i, a daughter in 1881, a son in 1882, and another daughter in

1885. Between 1880 and 1885, George Edward Gresley Jackson, then known as a retired British naval lieutenant, worked on a

project conducting a geodetic survey of the Hawaiian Islands. He surveyed 34 harbours and anchorages around the

islands, and produced “beautifully drawn charts… rich in detailed historical and cultural

information.”45 It is not clear what happened to George and Eustina after that, but according to the 1909

crocker-langley san francisco directory, Eustina Jackson, widow, was then living at

1733 Fulton Street, San Francisco. She died in Los Angeles on 1 January 1928. _______________ William Possenniskie’s youngest daughter, Helena (Lena), spent the last years of her life living with Ian’s Aunt

Marjorie, her niece, and Helena’s memories formed the basis of Marjorie’s notes. The Possenniskie’s life in early Auckland was divided into two: the time of “gay and pleasant parties”

before William’s wife became ill, and the sadness after she died. An excerpt from Marjorie’s notes: “My grandfather seems to have been of a stern nature, a truly Victorian

martinet. My aunt told me of an occasion in Melbourne, after the death of their mother, when Frederick did not get out of

bed when first called. My grandfather took a bucket of water to the bedroom and threw it over him. Cleaning up would not

have been a concern of his, or he might have thought twice about it. Cousin Mary was left with that task.” Helena may have confused Melbourne with Sydney, or the family may have moved again, but William Possenniskie senior

died on 2 August 1882, at his home at 424 Elizabeth Street, Sydney, aged 63. He is buried at the Waverley

cemetery.46 Eight months later, the widow Grace Possiniski [sic] married a David Fort. Marriage record states that she was 55. Six

years after that, Grace Fort married a John Cox. It is not clear what happened to the children immediately after their father died. Judging by the fact that Edward

spent the last years of his life living with his two unmarried sisters, the three probably remained together in the

family’s Sydney home. William junior was then 19 and Frederick 17, and probably did the same. Four returned to New Zealand. Frederick Henry remained in Sydney. He married Esther H White in 1902, and died at his

home at 76 Buckingham Street, Sydney, just a few hundred metres from his father’s house. He was 61, and is buried at

the Anglican section in Rookwood cemetery with his wife, who died 30 years later. His death certificate states that they

had no children, and that Frederick had been living in New South Wales for more than 50 years. Without exact names and ages recorded on passenger lists, it is impossible to pinpoint exactly when Edward, Rosanna,

Helena, and William junior returned to New Zealand. Shipping records show several Possenniskie passengers, but without

first names or initials, it is impossible to be sure of who they were: —In 1892, an E Possenniskie appears on the crew list as a “workaway” on the cargo

ship marioposa, which stopped off at Sydney on its way to Auckland. —In 1896, an E Possenniskie, a bookkeeper aged 47, so born the same year as Edward, arrived in

Auckland from Sydney off the anglian. —In 1905, a Mr and Mrs Possenniskie, aged 55 and 50, travelled to New Zealand with other

“Ladies & Gentlemen” in the saloon class on the mararoa. This could have

been Edward accompanying Rosanna or Helena—the “Mr and Mrs” was an understandable assumption to make for

two people travelling under the same surname—but they could also have been Henry Louis Possenniskie and his wife,

who were then still living in Auckland. —In 1906, the Mr Possenniskie of Poland in steerage with other “Labourers & Domestics”

aboard the tss moeraki that berthed in Wellington, could have been William junior, who

was a cooper by trade. —In 1907, a Miss Possennieskie, apparently related to Edward, travelled in the saloon class with

the other “Ladies and Gentlemen.” The vessel was the mokoia, and the

destination again Auckland. The four Possenniskie siblings were all living in Wellington by the time William junior, then aged 43, married Anne

Charlotte Ethel Strange-Mure on 28 October 1908. wises listed the newlyweds living

at 7 Pirie Street, Mount Victoria, Wellington in 1908, and later at 36 Abel Smith Street in neighbouring Te

Aro. William junior Possenniskie and his wife, Anne née Strange-Mure, circa 1936. According to electoral rolls, Edward, Rosanna, and Helena lived together at various addresses in Wellington.

wises had Edward living at 48 Oriental Parade in 1906. Helena, William junior, and Rosanna Possinneskie. More from Marjorie’s notes: “The two sisters kept boarding houses in Wellington, and I well remember them. Aunt

Rosie always wore embroidered or lacey blouses with small bones to keep the neckline high on her throat. With these, she

always wore dark woollen skirts, usually navy-blue serge, and for warmth on cold days, I understand she had a

three-quarter length astrakhan coat of black, which over the years faded to a greenish hue. “She was one of the severest women I ever knew, and I cannot remember that she ever smiled. I was somewhat afraid

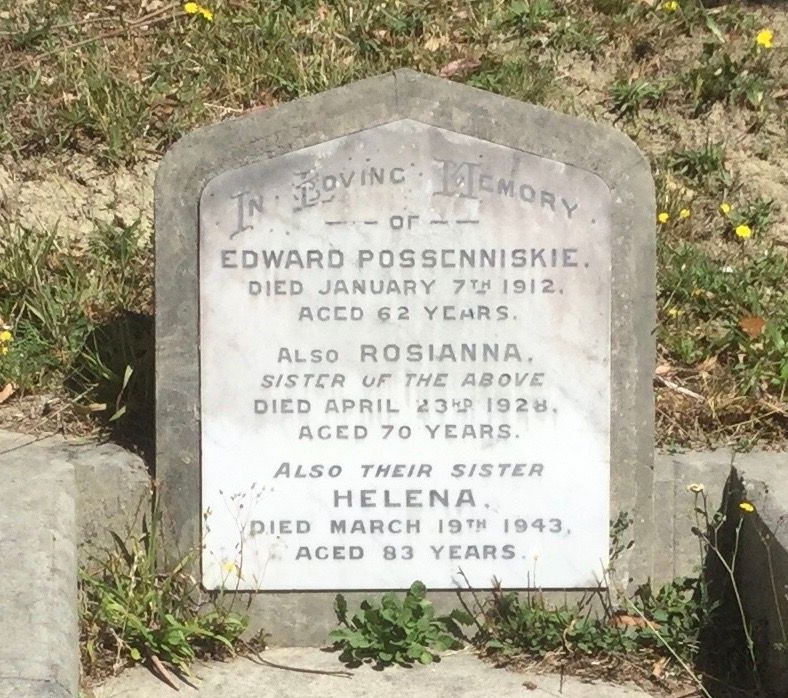

of her… Auntie Lena was a much easier person to know.” Edward died in 1912 aged 62, Rosanna in 1928 aged 70, and Helena in 1943 aged 83. They are buried together at the

Karori cemetery in Wellington. Edward, Rosanna, and Helena Possenniskie’s resting place at Karori cemetery in Wellington.

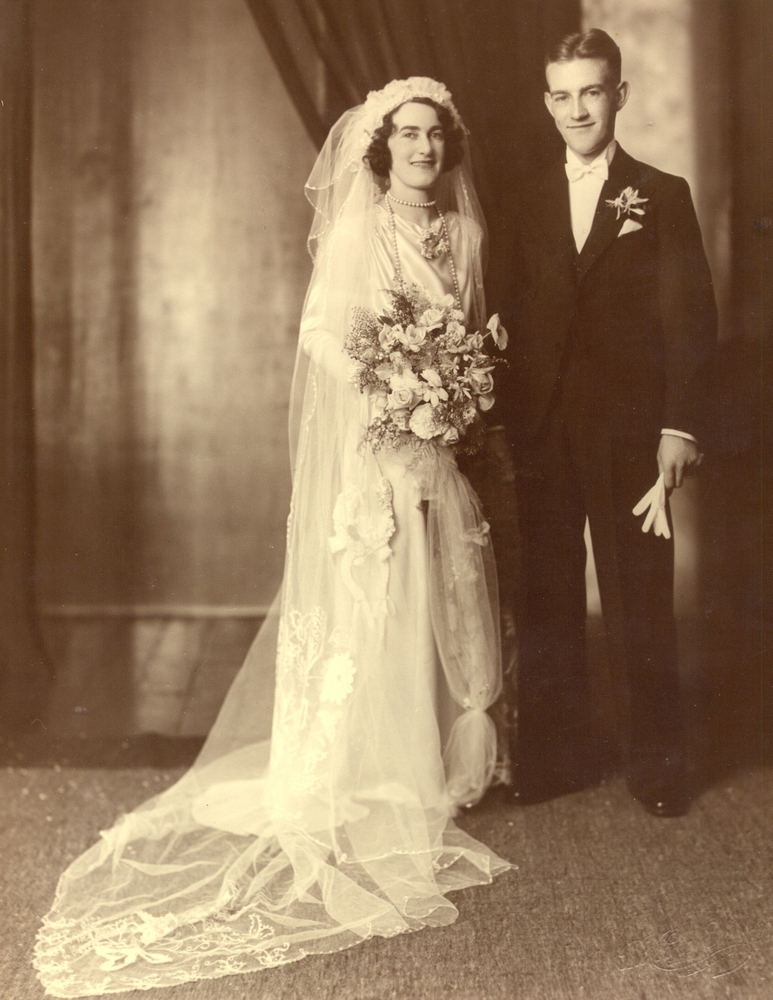

It is not clear why Rosanna’s name was spelt with an “i.” Their brother William and Anne had two children, William Francis Louis, and Ethel Marjorie. Marjorie Possenniskie as a girl and cutting the cake with her new husband Winfrey Lincoln.

Winfrey died in 1985 and Marjorie in 2002. Marjorie: “My father was a skilled craftsman, a cooper, and I regret to say that in my childhood I did not

appreciate his skill. I was too snobbish and felt that work in a brewery was not quite respectable. In Wellington, any one

brewery did not have sufficient work on a permanent basis, so there were several breweries that sought my father’s

services: McCarthy’s and Speights’s in Wellington, Harley’s in Nelson, and others in Greymouth, Hokitika, Reefton, and

Westport. “My father, who was over 50 when I was born, was in some ways more like a grandfather in his contact with me. On

wet weekends he had endless patience to teach me the alphabet [and] to count… “Friday evenings were an event in our lives. That was payday, and he always came home with two bags of sweets.

One was a bag of acid drops, and the other contained raspberry jubes. Those large jubes had a flavour all of their own,

and I have never tasted their like since.” William Frances Louis Possinneskie, known as Frank, suffered from rheumatic fever as a child and regularly spent many

months in hospital. “His doctor warned Mother that he would not live to manhood. Therefore, when Frank had begged permission to play

hockey, the doctor finally told Mother that he should be allowed to join in games with other boys and enjoy himself. “Exercise and fresh air did more for him than anything else, and he confounded the doctor’s prognosis. He became

a cabinet maker, one of the best… when he was making furniture prior to his marriage to Gladys Nairn of Wellington,

he was offered three times its market value by a man who declared that the workmanship was so outstanding.” William Francis Louis (Frank) Possenniskie married Gladys Florence Nairn on 15 February

1936. Frank died in 1966 and Gladys in 2002.

William junior is obviously a happy man at this gathering with his son, Frank, next

to him. Gladys next to Frank, and her mother, Henrietta Nairn and stepfather Phillip Wilson opposite, suggests this may

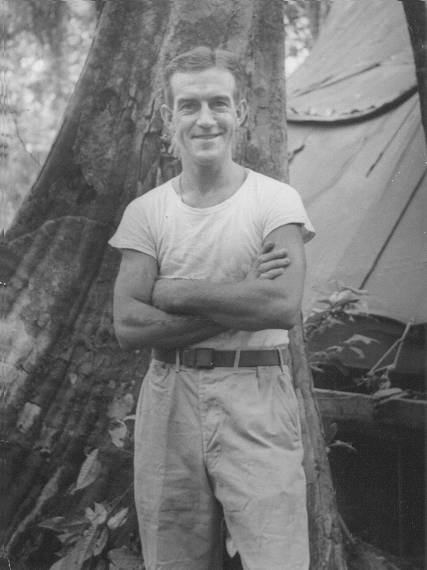

have been either an engagement party, or a pre- or post-wedding function. Frank served with the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force in WW2 in the Allied campaign in the Solomon Islands

against Japan. His and Gladys’s first son, Trevor Winston, was born in 1941, before he left. Barry Andrew and Ian Louis

were born after he returned, in 1946 and 1948. Frank Possenniskie during his time with the NZEF in WW2, probably on what was known as

Green Island. (Off Bougainville Island, it is now known as Fatkarsan.) His sister, Marjorie, wrote that his doctor had

been “astounded” that he was accepted for war service, and that he did not adapt to the tropical climate. Frank and Gladys Possenniskie with their eldest son, Trevor. The man on the right is

unidentified, but judging by the infant’s white clothing, the occasion could have been Trevor’s christening and the man

his godfather. This sombre studio photograph of Gladys and Trevor suggests that Gladys sent it to Frank in

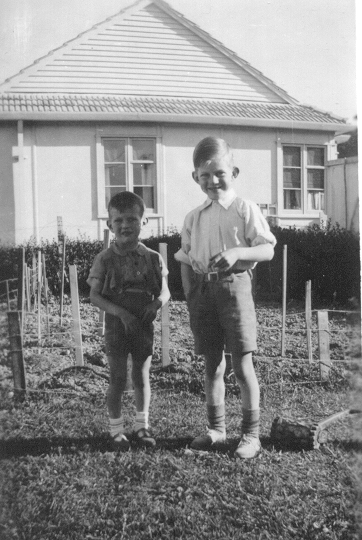

WW2 as a memento. Barry and Trevor Possenniskie at the family home in Naenae, Lower Hutt, where Trevor still

lives. Ian Louis Possenniskie and Christine Patricia Harrison, after their wedding ceremony in

1970. Frank Possenniskie died suddenly just days before Barry’s 21st birthday in 1966, and did not see his younger sons

marry: Barry to Frances Kirk in February 1968, and Ian to Christine Harrison in 1970. Both brothers had three children:

Barry and Frances had Blair, Dean and Natasha; and Ian and Christine had Samuel, Lucy, and Clare. At Gladys Possenniskie’s 90th birthday celebration in 1998, from left: Barry, Frances,

Christine, Gladys, Ian and Trevor. Although Frank’s sons and grandsons are still alive, his four great-granddaughters are making Ian face the increasing

probability that the unique Possenniskie name will die out. What will remain is Ian’s research. As with all families, the baton will have to be taken up by someone of a younger

generation and, as with any research, one never knows what remains to be uncovered… © Barbara Scrivens, April 2023. UNLESS OTHERWISE MENTIONED, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE POSSENNISKIE COLLECTION. THANKS TO PAPERS PAST, WHICH IS AVAILABLE THROUGH THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF NEW ZEALAND, TE

PUNA MĀTAURANGA O AOTEAROA. ENDNOTES:

https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc02Cycl-t1-body1-d1-d43-d3.html#name-425115-mention

http://www.enzb.auckland.ac.nz/document/?wid=4523&page=1&action=null,

The New Zealand Herald published his writings under the heading REMINISCENCES OF EARLY DAYS. No. 11

appeared on Page 1 of the supplement on 17 September 1887.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18870917.2.68.6

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/daily-southern-cross/1847/11/27/1

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18471201.2.2.3

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18471127.2.3

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31754363

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18471204.2.3

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18590729.2.10

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleonic_Wars

https://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/index.php?op=gt&lang=pol&bdm=B&w=07mz&rid=B&search_lastname=Pos*&search_name=&search_lastname2=&search_name2=&from_date=1818&to_date=1819&ordertable=[[0,%22asc%22],[1,%22asc%22],[2,%22asc%22]]&searchtable=&rpp1=100&rpp2=50

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18480412.2.7.1

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18511014.2.2.5

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18511203.2.9

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18511121.2.7.1

also in:

New Zealander, 22 November 1851, page 1, Advertisements Column 1,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18511122.2.2.1

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18520511.2.2.5

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18530924.2.2.3

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WI18520211.2.12

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18591123.2.6.5

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18660419.2.2.6

https://search.lma.gov.uk/captains-registers-pdfs/captains-registers-j.pdf

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS18730509.2.19.4

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS18730516.2.14.1

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS18741006.2.16.4

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18750429.2.19

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS18750430.2.26.2

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18750505.2.2.7

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZ18640901.2.9

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18720119.2.10

https://www.pdavis.nl/ShowShip.php?id=2260

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18720214.2.22

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18720408.2.2.7

https://www.thegardenisland.com/2010/03/04/hawaii-news/island-history-for-friday-march-5-2010/