The Uhlenberg Family

by Barbara Scrivens

In the heart of northwest Poland, in a Poland that did not exist geographically in the 1870s, Jan and Rosalia Uhlenberg had listened with caution to the news of a “better life” in New Zealand.

They had good reason not to believe the circulating rumours—stories based on promises made by German immigration agents, who for years had been enticing people to move to the new colony. Northwest Poland had been partitioned by the Prussian Empire since 1795,1 and life was becoming increasingly uncomfortable for ethnic Poles stubborn enough not to accept being germanised.

A northwest section of a 1712 map of Poland, when Poland and Lithuania still made up most of central and eastern Europe.

Jan and Rosalia, née Zielinska, had eight children. In 1873 their eldest, Paulina, had married Franz Kurz,2 then serving in the Prussian army in Gdańsk. By then, their eldest son, also named Franz, would already have served his three-year term of initial compulsory enlistment in the same army. Their second son, Joseph, 20 in 1873, if not already conscripted, was about to be. Their youngest son, August, was six.

Knowing that their sons would be conscripted into the army of an occupier—as well as their daughters’ husbands, future husbands, and any grandsons—did not sit well with the Poles, especially after the Prussian victory in the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War. It became the impetus for German Emperor William I, backed by his confident and powerful Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, to reclaim a kingdom, and to start in earnest his unification of various states into a single German Empire.

That victory stemmed from a surprising and humiliating defeat to the French 62 years earlier. Terms of surrender dictated by the French in 1808 officially reduced Prussia’s permanent military force from 220,000 to just 42,000.

The French may have thought that from then on, the Prussian army could be dismissed as a threat, but Prussian commanders re-thought its military structure, and created a method of secretly building a readily available reserve army of 320,000 to back a permanent force of 140,000.3

That the Prussians got away with more than trebling their 1808 allocation of permanent forces, suggests that the French did not bother to follow-up its own stipulation of the “permanent” 42,000. Any scrutiny of Prussian society from at least 1860 would have exposed the fact that every available man was beholden to the Prussian army for 20 years of his early adult life.

When news of an impending war with France spread in 1870, the Uhlenbergs, and other Catholic Poles living near them in the Kaszubian region, were approached by their German neighbour with a proposal: if they gave him the deeds to their lands, he would “arrange it with authorities” that they could spend their war effort in the fields, providing food rather than fight the French.

After the Franco-Prussian War, Poles living under Prussian rule were marginally less offended by the German-only language rule than by the outlawing of their Catholic faith.

Not only had the Poles little stomach for fighting for their oppressors, but they also knew that many of their countrymen would be fighting on the French side—a consequence of Polish soldiers moving to Italy and France after 1795, and forming Polish Legions that fought in the Napoleonic Wars.

Kaszubian Poles took the bait in 1870. After the war, their German neighbour refused to return their land deeds.

It is not clear how many times the above scenario happened, or between which parties, but it has been so often repeated in Kaszubian and Kociewian family stories that one must accept there had to have been some unscrupulous German landowners who took advantage of them. After all, in 1870, the area had been partitioned for at least 75 years. Not all the Poles had land deeds to bargain with, but for those who did and lost their land, severing that link made their lives even more tenuous than ever.

After the Franco-Prussian War, Poles living under Prussian rule were marginally less offended by the strict German-only language rule than by the outlawing of their Catholic faith—both introduced into law by Bismarck. Frank Uhlenberg was known to be among the few literate Poles who arrived in Taranaki, so Jan and Rosalia were not among the stubborn Poles who even before that war had refused to send their children to the only German-language schools.

By the time the last large group of Poles left Prussian-partitioned Poland in 1876, millions of people had already emigrated from continental Europe via Hamburg to new colonies all over the world. New Zealand was a bit-player in comparison to other larger, older, and more affluent colonies such as in North America, but it still needed labourers to continue the ambitious, mainly railroad, infrastructure scheme that Julius Vogel set in place with his 1870 Immigration and Public Works Act.

That last group left before Jan and Rosalia made their decision. Perhaps they did not want to leave Pauline, who had given birth to their first grandchild, Johann, in 1874,4 and who wanted to remain with her husband. There were at least four other Uhlenberg surnames in the area at the time, and several Zielinskis, so perhaps a large family base contributed to Jan’s and Rosalia’s hesitation.

In the end, Jan and Rosalia remained in Prussian-partitioned Poland with Joseph (born in 1853), Julia (born in 1856), Anna (born in 1859), [all born in Grabowo Kościerskie], Marianna (born in Koscierzyna in 1861), Mathilde (Matilda, born in Wysin in 1863), and August (born in Lubieszyn in 1867).

But they did send Franz to New Zealand in 1876. Young and single, he was exactly the kind of immigrant that the New Zealand colony advertised for, but more than that—his parents could trust him to tell the truth: Was it worth emigrating to New Zealand? He joined the more than 260 Poles aboard the fritz reuter.

_______________

Franz, or Frank as he became known in New Zealand, gravitated towards the Polish families who first settled in the Inglewood area in Taranaki.5 His reason may have been linked to Julianna Myszewska, born in January 1860, who was on the same ship.

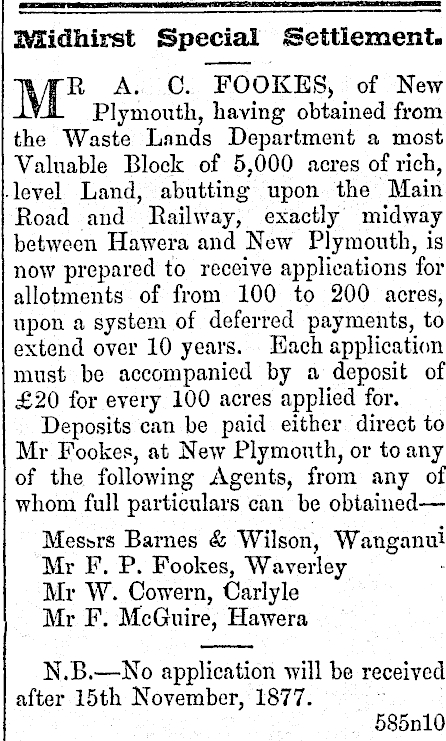

Franz Uhlenberg nominated his family as potential immigrants on 14 July 1877,6 and married Julianna at the Catholic church in New Plymouth a month later. Just two months after that, a Mr A Cracroft Fookes of Willowfield, New Plymouth, started to advertise “allotments from 100 to 200 acres” available at the Midhirst Special Settlement. Buyers had to deposit £20 for every 100 acres, in exchange for “deferred payments” extending 10 years. The applications closed on 15 November 1877:7

Sections in the aptly named Midhirst—between New Plymouth and Hawera—stretched across both sides of Mountain Road. Newspapers trumpeted its “very promising” prospects, its “good quality” land, and that the Mountain Road was “alive with workers.”8

Married men who arrived in New Zealand with families tended to stay in the growing Inglewood settlement—between New Plymouth and Midhirst—while they cleared the land they bought on its southern outskirts. August Neustrowski took several years’ removing strangling, shadowing bush on his York Road, Midhirst, land before he moved his family there in 1886. Mathias Dodunski and his family lived in Inglewood for 10 years despite his buying several other properties between Inglewood and Midhirst, all of which would also have needed basic clearing of standing bush.

Single men could be more adventurous.

Frank Uhlenberg was able to save enough from his bush-felling jobs to put a deposit down for land on York Road. He built a whare at the side of the river and settled there with Julianna. The land may have been advertised as “good quality” but there is no way that anyone selling it could have believed it was easily accessible, or ready to build on, or to live on. York Road was a line on a map. On whatever part of that road that Frank’s land lay, it would have been the same as all the rest—covered in huge, shading trees, knitted with supplejacks, and criss-crossed with gullies and streams. And in 1879, there would not have been enough people using the road to create any sort of track.

According to family story, Frank’s father, Jan, had been a teacher, so could not have misinterpreted his son’s letters. But Frank was careful about what he wrote to his parents. He glossed over the pain and emphasised the good about his new life and circumstances. He announced the birth of their first granddaughter, Barbara Franciska, born in June 1878. In April 1879, Jan received the “outfit money,” which potential immigrants needed to embark on the voyage to New Zealand, and which Frank sent.

By then, the colony had terminated its contracts with continental European sipping agents, so the balance of the Uhlenberg family travelled to Plymouth, on the English south coast, and embarked on the New Zealand Shipping Company’s orari. They must have been aware of immigration age restrictions because the shipping list recorded Jan, who was then 60, as aged 46, and Rosalia, who was then 61, as aged 44.

The orari arrived in Lyttelton on 26 July 1879—after 92 days at sea—with 11 saloon passengers and 283 mostly British immigrants. The Uhlenbergs were the only Poles, and there were three German families.

The orari at Gravesend, waiting to sail for Auckland in 1876.

The orari had visited New Zealand four times before, the first time in January 1876. In 1879, she remained in Lyttelton docks until 4 October. A cargo ship that size was not going to dispatch mere passengers at their preferred destinations along the New Zealand coastline. Its revenue came from cargo. It returned to London with its holds filled with wool, tallow, wheat, meat, hides, “12 casks sealskins” valued at £49,513, and 11 steerage passengers.9

Personal travel within New Zealand in 1879 was predominantly by sea. Passengers destined for other parts of New Zealand disembarked the main ship and took smaller vessels. Newspapers kept readers up to date with the sightings, arrivals, and departures of all the vessels owned by the many smaller shipping lines that connected various ports throughout the colony. The globe printed out the entire orari passenger list, and their passengers’ exact destinations.10 Frank would have been able to track his family’s whereabouts.

Most of the orari passengers remained in Canterbury. The steamer albion forwarded 109 to Wellington on 1 August 1879 before sailing to Hobart and Melbourne. The steamer wellington then picked up the 18 passengers bound for Nelson and Hokitika, as well as the 19 going to New Plymouth. It went south first, then returned north and anchored at the New Plymouth roadstead three days later.

The family story says that the Uhlenbergs spent a night at the Marsland Hill barracks, but it is unclear whether Frank joined them, or arrived the day after they landed on the beach at New Plymouth with two other families.

One can only imagine what the Uhlenberg ladies thought of sitting on rough wood, without cover, riding through thick bush while being bombarded by the smoke of the train’s coal engine.

Three years earlier, Frank Uhlenberg had walked out of the Marsland Hill barracks towards Inglewood, not knowing what to expect. This time, while well-aware of the improvements to the roads, and the new railway south, he must have been anxious for his parents’ and siblings’ approval of his new home.

Frank and Julianna had built a second ponga (tree-fern trunks) house on their York Road property. Frank had made a new table and chairs from lengths of tree trunks and had fitted a pane of glass into the window, apparently the first pane of glass fitted to any dwelling in the area. Julianna had cleaned, made new curtains to hang against the ponga walls, and made up the beds with fresh bracken mattresses.

The railway between New Plymouth and Patea was not yet finished. When the Uhlenbergs arrived in 1879, it ran to the not-yet-officially opened Mangonui railway station, then at the junction of York Road and the rail line that ran parallel to the still-unfinished Mountain Road.

The Public Works Department’s main concern while building the railways, was moving ballast, but it ran a side-line of passenger and goods services for the settlers, who appreciated the convenience of hopping on and off a ballast wagon rather than having to walk for hours for supplies. The ballast trains stopped wherever they needed to drop off or pick up a passenger or goods.

Dedicated passenger cars or covered wagons with seats were rare.11 Seats on the ballast trucks tended to be planks placed across the wagons. One can only imagine what the Uhlenberg ladies thought of sitting on rough wood, without cover, riding through thick bush while being bombarded by the smoke of the train’s coal engine.

As much as the train journey was an uncomfortable, unexpected experience, they still had to meet York Road at the end of a wet winter. Frank led them to his infant farm through tangled supplejacks, logs, and rampant climbers such as the thorned bush lawyers evolved to snag at anything that brushed past.

Julia and Anna Uhlenberg returned to New Plymouth the next day. Even if they had not already been offered jobs, they would have heard of many employment possibilities. Their parents may have been pushing the age limits but, judging by the free passage offered to single young women, the New Zealand government valued them over any other type of immigrant. Early ‘gentlemen’ colonists, and settlers who arrived later under Vogel’s scheme, always needed cleaners, nurturers, future wives, and future mothers.

_______________

The new colony had many new landowners wanting help to clear their acres of trees and undergrowth. Frank taught his brother Joseph the basics of bush-felling and he was soon employed, first in the York Road area, then towards New Plymouth.

Joseph was as diligent as his older brother. Within a year, he had bought two adjoining sections on York Road. Jan and Rosalia moved to Joseph’s farm, grew fruit trees, and kept bees. Jan Uhlenberg became known as John, or “Lul” to his grandchildren, and Rosalia, “Lulka.”

Rosalia Uhlenberg holds her arm around her eldest granddaughter, Barbara Franciska Uhlenberg, as they pose for this studio photograph around 1885.

The road improved over the years, and the bush was eventually tamed, but the family story recalls the children being sent shopping and coming home hours late and in tears thanks to ambush by camouflaged vines, thorns, logs, and muddy ditches. Jan and Rosalia built two small cottages close to each other, slept in one, and used the other for work and living quarters. They planted a large orchard, mostly apples.

Above the open fireplace, they hung hooks for their iron cooking pots. Another pot, free-standing and three-legged, they half-filled with ashes, then hot rata embers, which warmed the room or cooked potatoes.

They owned a few cows, set the milk in pans, skimmed it, and churned the cream into butter, which they exchanged at the local store for clothing or food.

Whatever skim-milk they did not use, they placed in one of the pots over the open fireplace. The whey went to their pigs and the curds became cheese. Apart from a few items, their little farm provided Jan and Rosalia with all they needed.

Joseph, who died of cancer in 1897, made special mention in his will that for the rest of their lives his parents were to retain full use of nine acres of his land, rent and charge free.

Jan’s grandchildren remembered him for reciting his rosary as he attended his trees, and always having a pot of honey or some fruit for them. He died in 1902, and is buried at the Midhirst Old cemetery.

Rosalia was an equally doting grandmother, who delighted in taking her grandchildren to the apple pantry and giving them an apronful each to take home. Anna Uhlenberg, who did not marry, moved in with her mother after her father died.

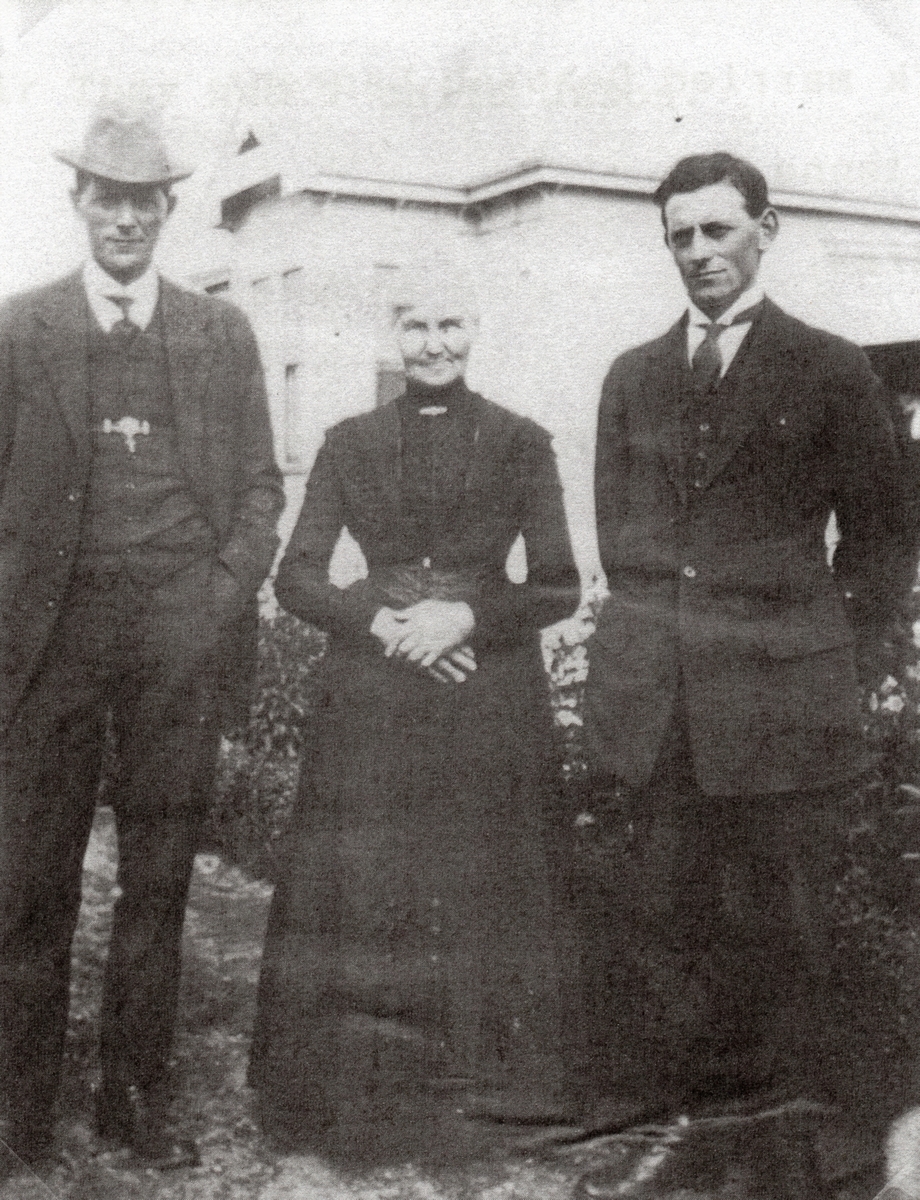

Rosalia Uhlenberg in 1910, shortly before she applied for New Zealand naturalisation.

After 32 years living in Midhirst, the widowed Rosalia decided to apply for naturalisation. She swore her allegiance to New Zealand on 26 July 1911, before Justice of the Peace Percy George Harkness, who described her as an “honest, sober, and an industrious woman.”

Rosalia signed her oath of allegiance with her mark, as did Joseph in his will, which described him as illiterate and unable to read, and which suggests families like the Uhlenbergs in Prussian-partitioned Poland may have been forced to make tough decisions about who to send to school.

Depending on which birth certificate one believes, the old lady was almost 100 when she died in 1916. She rests with her husband at the Midhirst Old cemetery.

_______________

Perhaps his brother’s illness prompted Frank to also made a will in 1897. Julianna’s younger brother, Jacob Mischewski, witnessed both the Uhlenberg brothers’ wills, signing himself as a farmer from Cross Road in Midhirst. The second witness on Joseph’s will was August Schroeder (Schrider) of Tariki Road, who had arrived with his family on the maraval in 1880, aged 19.

As York Road became more hospitable to traffic, the older Uhlenberg brothers were able to build up their dairy farms.

By the time Frank made his will, he and Julianna had five more children. The Births, Deaths and Marriages (BDM) index recorded them as: Johan Franz (John) in 1879, Frank junior (Francis) in 1881, Osmond Augustus (August) in 1883, Clara Agnes in 1885, and Annie in 1886.

His will shows that Frank senior clearly wanted to make provision for his young family and Julianna. Life forced him down a different path.

After Annie, came Mary Frances in 1888, twins Rosalie and Joseph in 1889, Martha in 1891 and Julia Helena in 1895. But Francis junior died in a horse accident in June 1901, aged 19, and Julianna died in July 1908, aged 48.

Julianna née Myszewski Uhlenberg with her seven youngest children. Standing at the back, from left are Clara, Anna and Rosalia. In front are Martha, and Julia holding her mother's hand to the left, and Mary and Joseph to the right. The caption in the Uhlenberg family story says it was taken around 1900, which was shortly after Barbara married John Kenealy.

By the time her mother died, Barbara née Uhlenberg had been married for nearly 10 years. It is unclear whether John and August, then 29 and 25, and single, were still living with their parents. Clara Agnes, 23 when her mother died, married Frank Patten four months later, so running the household after Clara left may have then fallen on Annie, 22 when her mother died, and who married Richard Latham in 1913—the same year that Rosalie married Theodore Cookson. Martha Cecilia had married William Gray in 1911. In 1914, Mary Frances married Frederick Betts, Joseph married Pearl Aubrey and Julia married John Tapp.

After 36 years spent transforming the raw bush into a successful dairy farm, Frank senior put it up for sale. His withdrawal from the sale in 1914 suggests that he may not have been ready to let go of the life he had built up there.

Unmarried John, with Joseph, had taken over much of the farm work and Pearl “kept house” for them. Frank shared the dairy takings with his sons. John lived in a whare close to the main house, where Frank, Joseph and Pearl lived.

The inquest into his death showed his obvious affection for his many married daughters, whom he visited often, his daughter Julia—then Mrs Tapp and living in Midhirst—almost daily. Julia and his daughter-in-law, Pearl, had both assumed that Frank was visiting his daughter in Waitara when he had not returned home on 23 December 1915. The family became worried when Julia visited her sister for Christmas to find their father missing.12

Frank was found dead, down a slope off the Mountain Road, by a dog belonging to a Fritz Kleeman, the manager of the Midhirst Dairy Company. The inquest jury could not find sufficient evidence as to what caused Frank’s death.13

The gravestone of Frank Unlenberg senior at the Midhirst Old cemetery. He lies with his wife Julianna, and their son Frank.

_______________

Frank’s brother Joseph married another of the fritz reuter passengers—Johanna Fabish, who was 10 in 1876. Johanna and her sisters, Francizka, Lucia, and Barbara then 14, 11, and eight months, were all born in Kokoszkowy.

After Franz Uhlenberg and the other fritz reuter passengers left for Taranaki, Johanna, her sisters, and her parents, Joseph and Anna née Sulewska Fabish, remained in Wellington while immigration agents decided where to send them. Their immediate group included Joseph Fabish’s brother Simon, and sister Anna Jakubowski, and their families—19 adults and children—and several others from the same region. They were apparently destined for the “special settlement” in Jackson’s Bay, but after they heard stories of the destitute life there, most of the Poles disembarked instead in Hokitika.14

(Joseph Fabish, settler, appeared on the Kumara [north of Hokitika] electoral roll in 1881 but, judging by where his niece and daughters married, he and his brother moved to Taranaki a few years later: Mary Jakubowski married Jack Mischewski in 1885, the same year Lucy Fabish married Michael Zimmerman. Johanna Fabish married Joseph Uhlenberg in 1886.)

Joseph and Johanna Uhlenberg had six children, Felix in 1888, Nicholas in 1889, Mary in 1891, Gertrude in 1893, Leo in 1894, and Matilda (Sister M Vivienne) in 1895. Leo died aged two months, and Matilda was aged 18 months when Joseph died in March 1897.

When widowed Johanna married Joseph Zimmerman in August 1899, she forfeited her right to live on the farm, and it is unlikely that she left her young children in the care of her then 81-year-old mother-in-law, Rosalia Uhlenberg. Johanna had seven more children with Joseph Zimmerman: Ted, Alexander, Peter, Joseph, Anthony, Johanna junior, and Kathleen.

Johanna née Fabish Uhlenberg Zimmerman died in 1950, and is buried at the Inglewood cemetery with her second husband.

_______________

At the same time as the sisters Julia and Anna Uhlenberg were taking the ballast train back into New Plymouth after spending the night at their brother’s farm in September 1879, a William Cottier was promoting his Masonic Hotel, on the corner of Devon and Brougham Streets. He took out numerous advertisements offering private rooms and bathrooms for families, and telling potential customers about his newly extended public rooms.15

The town’s Imperial Hotel sat a block farther north. The original White Hart Hotel, a block farther south, which had been used as a military hospital during the 1850s New Zealand Wars, had an expired liquor licence in 1873,16 so may not have been operating as a hotel in 1879.

Family story says that Julia looked after the Cottier’s children, and met one of the hotel’s many regular visitors, Nicholaus Schumacher. Julia and Nicholaus (then 24) married at St Joseph’s church in New Plymouth in September 1882.

There is no doubt that Nicholaus—educated in his Swiss homeland and Italy—was charismatic, and knew how to cultivate personal networks. He gravitated towards Midhirst.

Nicholaus’s parents, George and Anna (née Kasper), arrived in Tarananki two years before he and Julia married. He settled them in a cottage on the corner of Denbigh and Mountain Roads, Midhirst. Later, his sisters Christina and Barbara joined them.17

Julia and Nicholaus had seven children: Clara in 1883, Annie in 1885, George in 1887, Rosalia in 1889, Herbert in 1891, Felix in 1888 and Joseph in 1894. Rosalia died as an infant, and Herbert lived only one month.

On his naturalisation papers in 1882, Nicholaus described himself as a clerk. He worked for the Inglewood grocery firm Lever & Carter. He held positions as engineer for both the Manganui and the Moa Road districts, and was secretary for the Moa Road Board. He bought a section in “Mongonui” in 1881 and received permission to “capitalise” on it in 1885.18

Julia Schumacher with her sons George and Joseph, probably outside her house in Hamlet Street, Stratford.

It is not clear why Nicholaus kept interests both north and south of Inglewood, but in 1884, he became involved in erecting a public hall in Midhirst, which was built by the end of that year. In March 1885, the first meeting of the joint stock Midhirst Public Hall Company Limited appointed Nicholaus as its secretary. In 1892, when the Tariki and Waipuku schools separated, he became chairman of the Midhirst School committee, and elected chair again in 1893.19

In 1892, the taranaki herald declared that:

The appointment of Mr Schumacher as a Justice of the Peace has given general satisfaction. His knowledge of the languages and way of life of the German races will be of great service in the neighbourhood.20

It is also not clear why, in 1893, Manganui Road Board replaced him as engineer. Those who did not appreciate the board’s “dispensing with his services” gave him a gold watch and chain.21

That same year, Nicholaus moved his family to a small farm opposite his parents, possibly because he was already making plans to pursue “opportunities” in America, and wanted his wife and children near them.

The taranaki herald Midhirst correspondent, who covered Nicholaus’s farewell “smoke concert” at the Town Hall, wrote:

Mr Schumacher has proved to be a very useful settler, and takes with him the best wishes of many friends.22

The story did not mention his family. Clara was then 10, Annie eight, George six, and Felix two. Julia was pregnant with Joseph, who was born in March 1894.

Nicholaus Schumacher left New Plymouth, aboard the alameda, on 3 November 1893, bound for San Francisco and an “extended tour” in North America.23

He did not wait to vote in the general election on 28 November 1893, historical because, after a hard-fought campaign, New Zealand women gained the right to vote for the first time, the first in the world to do so. Julia had enrolled, and no doubt voted.

It is not clear how long Nicholaus continued to write to his family. In his last, he said he was coming to fetch them and settle them in America, but also that he was leaving for the Mexican border, to see for himself the “great opportunities” advertised.24 Julia did not hear from him again.

The woman who was brave enough to return to New Plymouth the day after she arrived at York Road in 1879, got on with the job of running the farm and bringing up her children.

Until her son George was old enough to help her, her younger brother August delivered her milk to the dairy factory.

Julia made sure that all her children received an education. She settled George and Felix on their own farms, on two sections that she bought on nearby Beaconsfield Road, south Midhirst, which the family felled, stumped, and grassed.

The Te Topo river made a loop through the original farm—the one that Nicholaus bought. In 1914, Julia objected to the council’s paying her 3d a cubic yard for stone it removed, when it paid her neighbour, a Mrs Baker, 4d. She had also heard that the council was “contemplating” paying her only 2d that year. She complained through her solicitor, Mr T C Fookes, and became the subject of a debate in the council chamber. Midhirst councillors discussed rivers, streams, boundaries, and payments for two hours before resolving to pay Julia the standard price for her stone—6d a cube.25

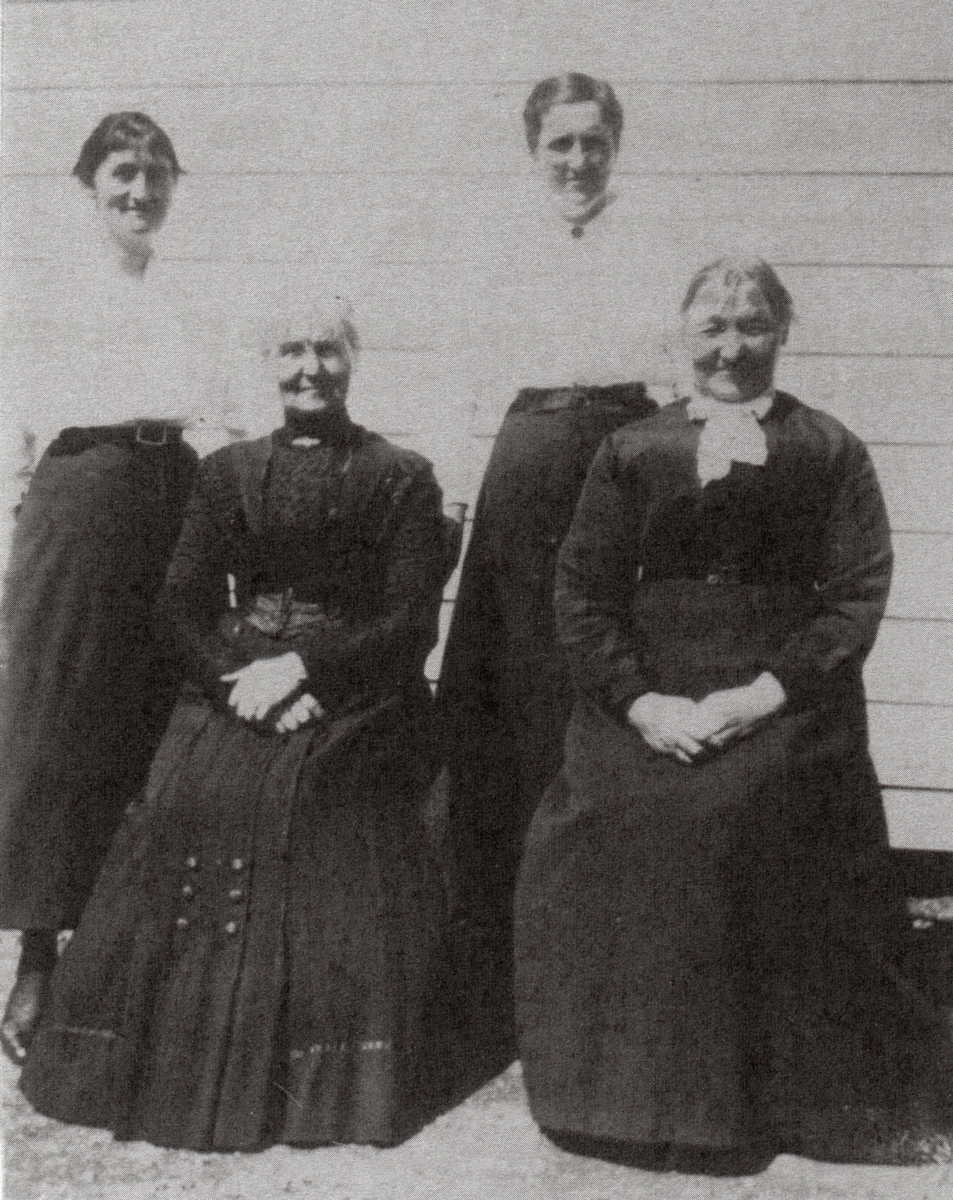

Rosalia Uhlenberg died four months before her grandson Joseph Schumacher married Agnes Breen in June 1916. Pragmatic Julia gave the original farm to her youngest child, bought a house in Hamlet Street, Stratford, and moved in with her daughter Annie, who married John Habowski in 1919. Julia’s sister Anna, who had been looking after their mother after their father died, moved in nearby.

Julia née Uhlenberg Schumacher, left, seated with her sister, Anna Uhlenberg. Behind them are Julia’s daughters, Annie and Clara, who married Michael Kowalewski in 1907.

Aged 60 in 1917, after 38 years spent working in New Zealand, building up farms and bringing up a family of five largely on her own, Julia found out that the government considered her an enemy alien. No matter how “useful” her husband had been for the region in the 1880s and 1890s, or what she and her children had contributed to New Zealand, or that her birth country was recorded as Poland, the still young, parochial country fighting under the Union flag distrusted her, and others like her.

At the outset of WWI, newspapers filled thousands of column inches agitating about “enemy aliens” living among the “righteous” and Taranaki had its fill of discrimination against anyone without a British-sounding surname. In New Zealand, then, married women automatically took on the nationality of their husbands, which cannot have sat comfortably with the world’s first women voters who married outside their nationalities. Switzerland was yet to become neutral.

Julia, at least, was not alone in Hamlet Street. Her daughter Clara married Michael Kowalewski in 1907. In 1916, he also felt the need to move, and suggested they buy the almost-finished house next door to his mother-in-law’s. Then, Midhirst was the up-and-coming town, and Stratford streets still covered in bracken, but for Julia, the move meant a shorter walk to Mass on Sundays. Therese Kowalewski, the youngest of Clara and Michael’s five children, recalled how her adored grandmother hummed Polish hymns as she gardened.26

Julia died in October 1944, aged 88, and is buried at the Stratford Kopuatama cemetery.

_______________

Anna remained single. After WWI, she made it her mission to become naturalised like her mother had been in 1911 and younger brother in 1900. Aged 60 and having lived in New Zealand for 40 years, she started the process through an official memorial declaration and a certificate of character from the Justice of the Peace Joseph McCluggage, who had known the family for 15 years.

In a letter dated 18 November 1919 and starting with the words, “I have the honour by direction of the Minister of Internal Affairs…” an Under Secretary J Hislop told her that New Zealand restrictions on naturalisation had been removed for alien “friends” only, and that she did not fall under such a category.

Anna sent in another application. By January 1920, she had instructed Joseph McCluggage, also her solicitor, to enquire why she had received no reply. Hislop reiterated that Anna and a “Mesdame Groshinski” were technically still alien “enemies” and needed to wait for the issue of a Proclamation of Peace.

Anna was having none of that, and approached her local MP, Robert Masters, who wrote to then Minister of Internal Affairs William Downie Stewart junior in August 1921: Anna had made an application, had paid the “usual fee,” and wondered whether her papers had been “overlooked.”

A few days later, MP Stewart wrote to MP Masters to say that, if Anna could prove that any blood relative had served with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, he would consider granting her naturalisation.

The signatures on a Department of Internal Affairs letterhead are illegible, but on 8 September 1921, Minister Stewart received a memorandum which stated Anna’s father was naturalised in 1899, her brother in 1900, and that three of her nephews had served with the NZEF:

… Mr Masters further stated that the Uhlenberg family are of Polish decent and are bitterly opposed to the Prussians.

Nationals of Poland are treated as friendly aliens27 and provided the Memorial is recommended by the Stipendiary Magistrate for the district I think that the Memorialist should be accepted as a Polish subject and granted naturalisation…

The Stratford Magistrate wrote to the Under Secretary for the Department of Internal Affairs—probably still Hislop, as his signature appears in a later letter—to say that he was recommending Anna’s naturalisation, and that of John Jacobowski.

Anna Uhlenberg received her naturalisation on 27 October 1921.

Hislop sent her the papers on 1 November 1921, but it was not the last he heard from the family: Anna’s nephew-in-law and neighbour Michael Kowalewski continued to petition for John Jacobowski, “as the old Gentleman is feeling uneasy at the long delay.”

(John Jacobowski was Jan Jakubowski who arrived on the Fritz Reuter with Anna’s brother Franz, and who had been among the Poles sent to Hokitika. His naturalisation came through on 9 December 1921, when he was 87. His wife, also named Anna, died within a year, and he died in October 1923.)

One Saturday afternoon in July 1927, on her way home from the train station, Anna bumped into Michael’s wife, her niece Clara Kowalewski, and Clara’s daughter Therese, who had been born at their Hamlet Street home in 1923. Anna told them that she had just spent a “lovely holiday” with her younger sister, Matilda Jans, in New Plymouth, and promised to come for dinner the next day to tell her more.

Anna gave three-year-old Therese a penny outside the old Manoy’s Drapery Store, now Stratford Café & Bakery, but it fell between the gratings in the footpath.

The old Manoy’s Ltd sign is still visible on the building, the lower floor partly obscured by a Uhlenberg Haulage Ltd van that happened to be driving past when this Google maps image was taken.

When Anna did not arrive for dinner, Clara sent her children to call her. When they returned saying that the house was locked and that they had had no reply from their knocking, Clara went to investigate. She, too, could not get a response, and asked a neighbour to call the police, who forced entry and found Anna dead on the bathroom floor. The scenario in the house suggested that suggested that Anna had prepared the fire for lighting, placed bacon in the pan, ready for breakfast, and gone to her room to dress for Sunday Mass when she collapsed and died.

Anna joined 14 other Uhlenbergs in the Midhirst Old cemetery, the last of her family buried there.

_______________

It is not clear when, but family story says that Maria Uhlenberg moved to Auckland and worked as a housekeeper in a hotel. She met her future husband, Samuel Neill, a coal-miner turned flax-grower—or the other way round—and moved with him to Kawakawa in Northland.

Maria became known as Mary. She and Sam had six children: Annie, Margaret, Phoebe, Joseph, John Vincent, and Samuel junior.

Maria née Uhlenberg Neill. Her leather gloves and riding crop suggests she was a horsewoman. Unless the fence she is leaning on was a photographer’s prop, this image could have been taken at their farm, the background the Northland hills.

Samuel senior died on 30 April 1939, aged 78, and Mary on 17 February 1951, aged 90. Both are buried at the Kawakawa cemetery. Because she married a British man, her name did not appear on any alien list, and nor did she need to be naturalised a New Zealand citizen.

_______________

Matilda Uhlenberg turned 16 three weeks before the orari sailed into Lyttelton harbour in July 1879. It is not clear why, with a father who was a teacher, she remained illiterate. Perhaps pragmatism trumped a more formal education for Matilda during those first years in New Zealand. Like other Polish settler children, she would have helped in the house and the farm, and perhaps Rosalia knew that her daughter needed practical skills to attract paid work.

Family story has Matilda working as a housemaid for a doctor in Hawera. Next to her “mark” on her sister Anna’s estate papers in 1927, is an explanation of her illiteracy.

Matilda née Uhlenberg Jans.

Like her sister Julia, Matilda married a Swiss man. She and Kaspar Joseph Jans exchanged vows in July 1887, a few weeks before Kaspar’s brother Karl Oswald and Barbara Potroz did the same.

Matilda and Kaspar, a butcher, lived on a farm in Tariki, where their first three children were born: Joseph in 1888, Ann Helena in 1891, and Conrad Leo in 1892. After Conrad drowned in a river, the family moved to New Plymouth, where Kaspar had his shop near the Huatoki stream, and where Mary was born in 1896.

The family suffered another tragedy when Ann Helena fell of a stage and injured her spine in November 1900. She died more than a year later at their home in Vivian Street.

Joseph Jans married Mary Margaret Mischewski in 1913, and Mary Monica Jans married Anton Kowalewski in 1926.

Kaspar died, aged 83, in 1948 and Matilda three years later, aged 87. They are buried together at the Te Henui cemetery in New Plymouth.

_______________

August Uhlenberg belonged to a group of several Polish teenagers and young men who developed an aptitude for languages. At 14, acting as interpreter, he rode around the area with Colonel William Malone as the latter gathered funding for a Catholic church in Stratford. The building opened in 1883 and doubled as a school.28

The young man could not have failed to absorb his parents’ and siblings’ work ethic, and that of the other settlers. Family story tells of the farm he bought next door to the Mischewskis on York Road, and that he built his house on a hill.

He earned the deposit partly during a contract for felling trees on the Eltham-Opunake road. The men in his party heard a huge boom, and several smaller explosions, while they camped near the Kapuni stream in June 1886. A week later, they went into Eltham for supplies, and heard that Mount Tarawera had erupted, buried nearby villages, and obliterated the famous Pink and White Terraces.29

Aged 20 in 1887, August married Mary Kowalewska, a year younger, and who arrived on the fritz reuter with her parents, Jakub and Barbara (née Bunikowska), and siblings Wincenty (Vincent), Franciszek (Frank), and Jakub junior (John).

This photograph of Mary Kowalewska and August Uhlenberg was apparently taken after they married at the Catholic church in New Plymouth on 5 July 1887.

Their first child, William, does not appear on the BDM under Uhlenberg, or any logical derivatives. Polish settler Joseph Fabish, however, wrote in his diary that Mrs August Uhlenberg gave birth to a boy, William, on 8 July 1888.30

Joseph Fabish listed a second son born to Mrs August Uhlenberg on 1 April 1890, but did not name him. This time, the BDM did. It recorded Francis Theodore’s birth to May and Augustus Uhlenberg, and his death aged one week. Joseph Fabish made a note that the “little boy” died at seven days.31 It is not clear where he was buried.

Mary née Kowalewska Uhlenberg died three days after the birth of their third son, John, who lived for seven hours on 13 May 1891. Both are buried at the Midhirst Old cemetery.

It is not clear who helped August look after his almost three-year-old motherless son, but there cannot be doubt that his large extended family rallied around their youngest son and brother.

At around that time, the late Mary’s paternal uncle Jan had become disillusioned with life in the USA and decided to join his younger brother in New Zealand. He arrived with his wife, Franciska, and two of their children, another Mary (18) and Michael (9).

August employed the second Mary Kowalewska to housekeep and look after William, and they married in April 1893. William soon had half siblings to keep him company—Agnes, Paul, Lucy, and Sydney were born during the first five years of their marriage—but August was restless. He longed for his homeland.

On 20 July 1898, August sold his York Road farm to Frank Lehrke, who paid him with 1,000 sovereigns. The day August collected his money in Stratford, he took his nieces Clara and Annie Schumacher, then 14 and 12, with him. The girls helped him carry the money home in their purses.

The next day August and his family returned to the place of his and Mary’s birth, an area of Poland still partitioned by the Prussians. Pauline née Uhlenberg Kurz met them. August intended to live with her while he found a job and their own home, but he quickly discovered that reality 18 years after he left, differed vastly from his fond memories as a 12-year-old.

His brother-in-law Franz Kurz had prospered since August last saw them. Although he had clothed himself and his family in the best that New Zealand could offer, fashions in the colony clearly did not reach the standards of continental Europe. Before introducing August to his friends, Franz insisted he buy a new outfit.

August found it impossible to pick up old relationships or make new ones. Old friends were gone. Worse, William and Agnes contracted diphtheria, and both died after short illnesses. August and Mary returned to New Zealand in 1899 with Paul, Lucy, and Sydney—and Clara (Clare) who was born at sea.

Back in New Zealand, the family stayed with August’s parents until he bought a 200-acre piece of standing bush on Mountain Road, Waipuku. This time, August embraced his adopted country, and became naturalised as a New Zealand citizen barely a year later.

Mary and August had nine more children: Michael in 1901, Marion in 1903, Rosalia and Frances in 1904, Annie in 1905, Eleanor in 1907, twins Patrick and James in 1908, and George in 1911. Rosalia died aged two months, and her twin sister Frances at five months. Sydney died aged seven in 1905.

In 1907, August spent 22 guineas on a two-year-old bull called Rosebud’s Magnet. It is not clear whether this was his first serious buy, but August immersed himself in improving his dairy herd, and in 1910 was accepted into the New Zealand Jersey Breeders’ Association.32 He was elected to the board of the Midhirst Co-Operative Dairy Factory Co Ltd in 1911, and re-elected several times. By 1927, he had a reputation as a “veteran breeder.”33

August and Mary Uhlenberg with their surviving children, circa 1920. From left, back: Michael, Clare, Paul, and Marion; seated: Annie, Lucy, James, and Eleanor; in front: Patrick and George. Michael was ordained in 1926, and Eleanor took her vows in 1930, and became known as Sister Stanislaus.

Mary née Kowalewski Uhlenberg, mother of 14 children, died aged 62 in 1936, and did not see her ordained son, Michael, perform the double wedding of his youngest brothers, George, and James, to the Dwyer sisters Brigid and Kathleen, in May 1937.34

August matured into a pillar of his community. The teenager who rode with Colonel Malone to secure funds for the Stratford Catholic church was among those who made sure that the church recognised its founders. In 1929, parishioners erected a “splendid memorial” wall for the church’s first priests, and pioneers like Colonel Malone, who died on the Gallipoli peninsula in 1915. It also recognised Polish pioneers such as August’s father, then known as John Uhlenberg, who died in 1902, Michael Dodunski, who died in 1919, Anton Potroz, who died in 1926, and August Neustrowski, who died in 1927.

The original Uhlenberg homestead on Mountain Road. The woman in the apron was probably a nanny, and the two boys behind the dogs were either Patrick, James, or George. The house was extended but the property remains in the family, passed down to Patrick Uhlenberg and then to his son, Paul.

August loved his home in Waipuku and lived there permanently until a few years before he died. Although, like other farmers in the area, he cleared bush for his farm’s needs, he grew to appreciate the district’s native shrubs and trees and kept a vast collection.

His son Patrick took over the farm, and August spent a few months at a time visiting various children, but always returned to Waipuku. He had a room overlooking the driveway lined with his precious native bush. His granddaughter, Joan Dickson, daughter of Patrick’s twin, James:

“When we used to go and visit, we’d wander into the bush, and grandad would be on the veranda and shout, ‘You get out of my bush! Don’t you go breaking any of my trees!’”

August Uhlenberg died aged 94, and was buried at the Kopuatama cemetery with his second wife, Mary. His son the Reverend Father Michael Uhlenberg officiated at his funeral.

© Barbara Scrivens, August 2021.

ALL FAMILY PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE UHLENBERG-DICKSON FAMILY COLLECTIONS AND ARE USED WITH PERMISSION.

THANKS TO JOAN DICKSON, WHO WROTE THE ORIGINAL FAMILY STORY.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 This was the third partitioning. The first had been in 1775, and the second in 1792.

- 2 Spelling variations include Kus, Kusch and Kush.

- 3 Grey, Wilbur E, Prussia and the Evolution of the Reserve Army: A Forgotten Lesson of History, pages 3 & 10, unclassified document, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 1992.

- 4 Pomeranian Genealogical Association,

http://www.ptg.gda.pl/index.php/certificate/action/searchB/ - 5 For more about the first eight Polish families in Taranaki, see Under the

Mountain, Layers in the Mille-Feuille of Taranaki History,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/under-the-mountain/ - 6 Pobóg-Jaworowski, George, History of the Polish Settlers in New Zealand, page 85. Published by CHZ Ars Polona, Warsaw,1990.

- 7 One of the advertisements: this from The Patea Mail, page 3, 27 October

1877,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/PATM18771027.2.14.3 - 8 The Patea Mail, page 2, 17 October 1877,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/PATM18771017.2.6 - 9 Lyttelton Times, 4 October 1879, page 4, SHIPPING,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT18791004.2.8 - 10 Globe, page 2, 28 July 1879, Shipping,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/GLOBE18790728.2.3 - 11 Scoble, Juliet, Names & Opening & Closing Dates of Railway Stations in New Zealand 1863 to

2010, pages 3 & 64, researched and written for the Rail Heritage Trust of New Zealand,

http://railheritage.org.nz/assets/Dates_and_names.pdf - 12 Stratford Evening Post, 5 January 1916, page 5

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19160105.2.11

It is unclear which of the other daughters Frank was visiting. If anyone knows, and lets us know, we will add her name. - 13 Ibid.

- 14 For more about the failed Jackson’s Bay settlement, read Jackson’s Bay, 1874-1879: Resolutely

Untamed,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/jacksons-bay/ - 15 Taranaki Herald, 11 September 1879, page 2, Casting at Vivian’s Foundry,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18790911.2.6 - 16 From The Industrious Heart, A History of New Plymouth,

http://history.new-plymouth.com/15/152 - 17 Ibid, Pobóg-Jaworowski, page 87.

- 18 Stratford Evening Post, 22 March 1932, page 2, Butter at Sevenpence a

Pound,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19320322.2.3,

Taranaki Herald, 5 December 1884, page 2, County Council,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18841205.2.12,

Taranaki Herald, 2 March 1881, Land Board,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18810302.2.9,

Hawera & Normanby Star, 19 March 1885, page 2, Land Board,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HNS18850319.2.11 - 19 Ibid, Stratford Evening Post above, Butter at Sevenpence a Pound.

Taranaki Herald, 26 April 1893, page 2, School Committee Elections,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18930426.2.13 - 20 Taranaki Herald, 14 May 1892, page 2, Stratford News,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18920514.2.14 - 21 Taranaki Herald, 8 July 1893, page 2, Stratford News,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18930708.2.23 - 22 Taranaki Herald, 7 November 1893, page 2, Midhirst,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18931107.2.21 - 23 Taranaki Herald, 3 November 1893, page 2, Heller’s Bonanza Coterie,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18931103.2.5 - 24 Dickson, Joan, Uhlenberg, page 42.

- 25 Stratford Evening Post, 17 December 1914, page 8, MIDHIRST MATTERS, THE ROYALTY

QUESTION,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19141217.2.56 - 26 For more on Sister Therese Kowalewski:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/therese-kowalewski/ - 27 Ibid, Under the Mountain… Poles in Taranaki involved in the disputed Stratford elections later in 1919 would dispute that assertion.

- 28 Hawera & Normanby Star, 27 October 1883, page 2, NEWS AND NOTES,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HNS18831027.2.5 - 39 Thanks to George Uhlenberg’s wife, Brigid, who gave the additional details about August to Joan Dickson when she discovered Joan’s interest.

- 30 Baptised William Joseph at the Catholic church in New Plymouth on 17 July 1888.

- 31 From Joseph Fabish’s lists.

- 32 Taranaki Herald, 14 September 1907, page 8, MR NEWTON KING’S

REPORT,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH19070914.2.81.1

and

Manawatu Times, 22 August 1910, page 4, Untitled,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19100822.2.11 - 33 Stratford Evening Post, 11 July 1927, page 4, LOCAL AND GENERAL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19270711.2.12 - 34 Patea Mail, 21 May 1937, page 3, DOUBLE WEDDING,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/PATM19370521.2.21 - 35 Stratford Evening Post, 11 August 1929, page 3, WALL OF REMEMBRANCE,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19270811.2.9