Therese Kowalewski

Therese Kowalewski returned the draft of this story within a week. Considering our postal service has been cut to three deliveries a week, I knew she had received it, read it and posted it back almost immediately.

That she had read and returned her story so quickly revealed her personality and agile mind and why, at 94, she is an inspiration.

Therese’s nephew, John Hartley of Hokitika, suggested I interview her about their shared family, the Kowalewskis of Taranaki. He spoke of his admiration of her and her continued ability to recall names and events, and she proved him correct.

Therese’s grandparents, Johann and Francizka Kowalewski arrived in New Zealand in 1893, 20 years after the first Kowalewski family. With them were Therese’s father, Michael, and aunt, Mary.

Therese helped another relative, Mary Dettling, compile a family book about Michael, Mary and their older brother, Joseph Kowalewski. This story expands on her reflections about her life as a Polish blacksmith’s daughter growing up and growing with the Taranaki town of Stratford.

I thank Therese for her time, her patience and her hospitality.

Barbara Scrivens

THE BLACKSMITH'S DAUGHTER

by Barbara Scrivens

The smell of black bread baking and the taste of that bread eaten with homemade butter and cheese were childhood memories Michael Kowalewski never forgot.

Michael recollected little of his Prussian-governed Polish homeland but spoke freely to his family of his father coming home exhausted after working all day for their German overlord and of his mother continually doing chores around their home—milking the cows, caring for the other animals and harvesting—and the meals she created in the kitchen, like potato pancakes (placki). Michael left that home, aged seven, his final memory the excitement of packing their few belongings and settling sail for America with his parents and sister.

The youngest of 10 children born between 1861 and 1883,1 Michael does not remember ever meeting his oldest brother, Franz, born in 1864. The Prussian military conscripted all eligible men from the age of 20, so Franz would have left home when Michael was barely 14 months old. After three years’ training, men remained on call until they were 39.2

“The German army treated the Poles very, very badly. When [Franz] came home, he said to his father, ‘Don’t let the other boys go.’ Because he had been in the army, he wasn’t allowed to leave [Prussian-partitioned] Poland.”

Several years later in New Zealand, Michael did not recognise another of his older brothers, Joseph, 12 years his senior.

“My dad was driving cattle down the road wearing somebody else’s cut-me-off clothes, and this flash man walking up the road said to him, ‘Hey little boy, do you know where the Kowalewskis live?’ And my dad said, ‘Yeah, up there in that house.’

“And so Joe thanked him and off he went. When he arrived, his mum and dad asked, ‘Did you see Michael?’ ‘No, I only saw a dirty little scrubber with some cows.’

“Joseph didn’t recognise his little brother and dad only knew who he was when he came home. I used to laugh over that.”

_______________

Boys predominated in the Kowalewski family. At least four of Johann Kowalewski’s brothers had left Prussian-partitioned Poland in the 1870s so one can only surmise why he did not follow them sooner.

Johann Kowalewski had four sons by the time “Lorenz Aug”3 Kowalewski arrived in Port Chalmers with his family in 1872. Franz Anton Kowalewski4 disembarked in Wellington with his family in 1875 and in 1876, Jakub Kowalewski followed with his family on the fritz reuter, whose passengers became the last immigrants that the New Zealand government accepted from continental Europe. The first two Kowalewskis began new lives in the South Island. Jakub joined the Poles in Taranaki.

According to family story, another unnamed brother, made his way to the Hamburg docks in 1877, joined the crew of a ship he thought was bound for New Zealand, arrived instead in America and settled in Cleveland, Ohio.5

Was it only poverty that kept Johann from following his brothers earlier? Or did the reason have more to do with other family ties, injury or illness? The family story says that Johann and his wife, Francizka (née Kobierzynska), had 10 children, but lists only seven. Illness and deaths of three children would explain the nine-year gap between Marianna (known as Mary) and Michael.

Franz’s pleadings to his father not to allow his brothers to follow him into the army may have been the push Johann needed to save the balance of his family. When Franz married German woman Pauline Schultz, left, in 1888 and moved to Germany proper, his father may have felt there was nothing more to keep him in his Prussian-occupied homeland.

By the time the Kowalewskis packed for America a year later, the family had shrunk to four: Johann, Francizka, Mary, then aged 16, and Michael.

In about 1885, Johann had sent his oldest daughter, Clara, and second son, Johann junior, into the care of their unnamed uncle in America. Clara was then 24 and Johann junior 18 and ripe for imminent conscription. Their uncle helped them find jobs and they settled in America.

Clara and Johann junior sent money back to their parents. This paid for the passages to America of two more sons, the older one thought to be named Jakub, and Joseph, born in 1871. Besides their inevitable future conscription into the Prussian army, the German overlords used young Polish men as cheap labour. The brothers disappeared with only the clothes they wore.

“The German overlord came looking for them and was told, ‘We don’t know where they are. They went to work. We’re expecting them to return. Look, here are their clothes.’”

Joseph continued to fear that authorities would deport him back to Prussian-partitioned Poland. He hid his Polish birthplace on his 1897 marriage certificate, stating he was born in “America” rather than Pinczyn, Poland.6

Johann senior did not transplant well, despite living close to most of his children and their growing families in Cleveland.

“Grandfather was a religious man and he didn’t like America. His brother Jakub must have invited him to New Zealand because after two years in America, he came here with my grandmother and my dad. The other children stayed in America with their cousins.”

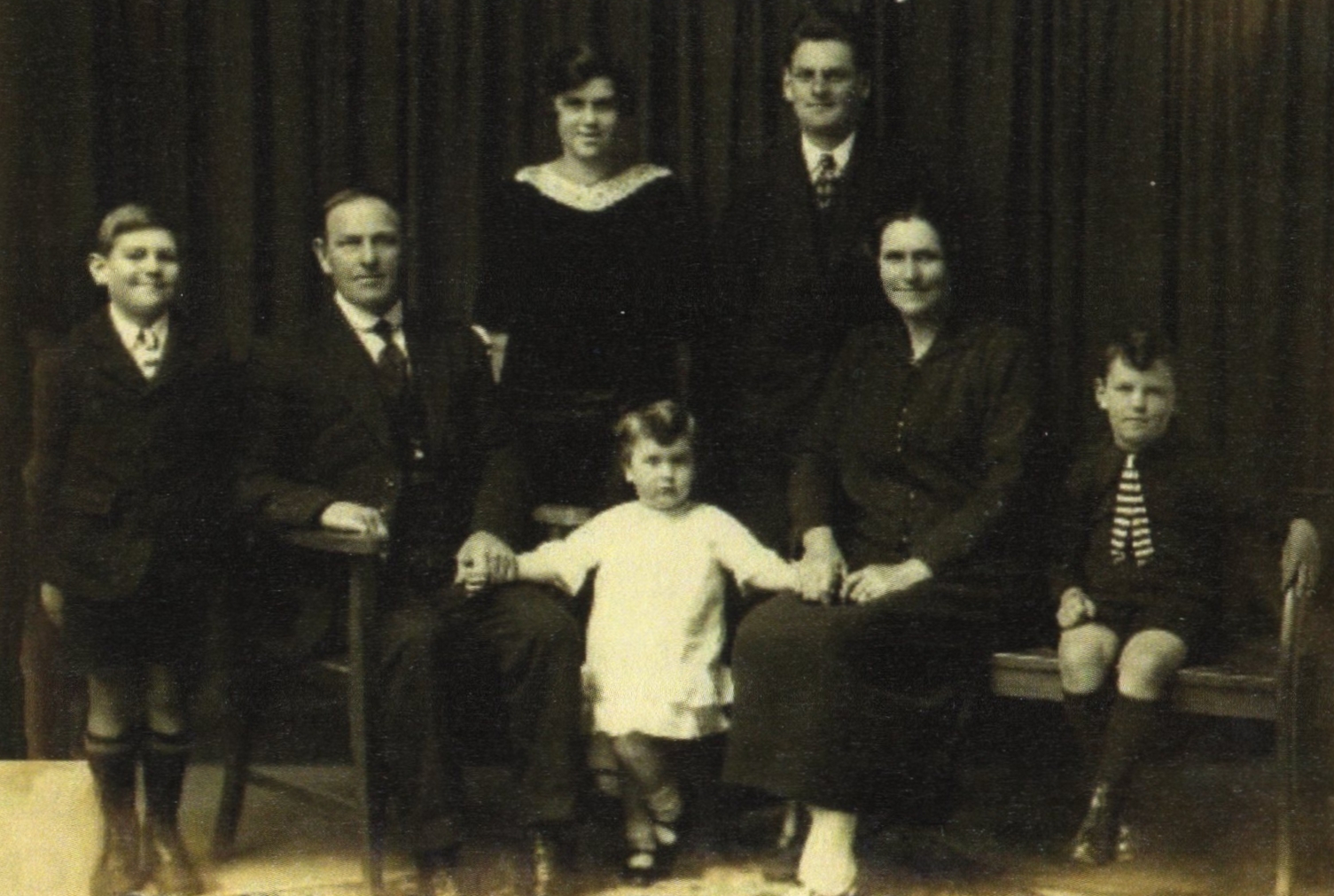

Johann and Francizka Kowalewski in America with Mary and Joseph standing and Michael in front. If anyone can identify Johann’s ribboned medal, please let us know through our get in touch page.

Michael disputed whether his sister Mary left America with them but she appears with the family on the british princess passenger list from Philadelphia, which arrived in Liverpool on 26 January 1893.7

That hand-written passenger list clearly shows the Christian names Jan, Franziska, Mary Anna and Michael. It is not clear at which English port the family disembarked but they boarded the 6,057-ton oroya, which left London on 27 January 1893 and deposited passengers in Auckland, Wellington, Lyttelton and Bluff between March 11 and 13. On the oroya the Kowalewskis became John, Johanna, Mike and Mary.8

The anglicising of their Christian names on passenger lists is no surprise considering the family left English-speaking countries and needed to transfer ship. Mary’s name on the passenger lists does not tally with the stories Therese heard about her aunt, who later married widower August Uhlenberg.

August’s wife, Mary and Michael’s cousin, also named Mary Kowalewski, had died in 1891 aged 23, three days after giving birth to her second son, John, who lived for seven hours. Her elder son, William, was then aged two.

Therese heard that August’s father-in-law, her uncle Jakub Kowalewski and the late Mary’s father, told August about his niece Mary in America: that she would to housekeep for him and look after William if he paid her passage.

Jakub Kowalewski met Johann and his family on the New Plymouth wharf. Jakub lived on Croydon Road, near the Manganui river between Tariki and Midhirst, and had built a ponga whare (a hut made of tree fern logs) near the river as temporary accommodation for his brother and his family. If Mary immediately started working for August, it would explain why Michael did not remember her at home with him and his parents.

The second Mary (née Kowalewski) Uhlenberg returned to Prussian-partitioned Poland with her new husband in 1898. August, 12 when he left his homeland in 1879, had longed to return. He sold his New Zealand farms and intended to resettle with the proceeds. He and Mary left with their children William, Agnes, Paul, Lucy and new baby Isadore but, according to the family book, “it was impossible to pick up the threads again. People were different, old friends had gone…”9 William and Agnes contracted diphtheria and died. The family returned to Taranaki after 16 months and Clara was born at sea on the return voyage. Mary and August started farming in Waipuku and had nine more children.10

Mary and August Kowalewski, right, on holiday with children Lucy and Michael and “Guide Rangi.”

_______________

Michael Kowalewski was not one for classrooms. He was not quite school-going age when he left Prussian-occupied Poland but spoke Polish and German. He told Therese he had attended school in Cleveland, Ohio “on an irregular basis” and in New Zealand for “a day.” He had learnt English in America so could communicate with English-speaking settlers more easily than the earlier Polish settlers who arrived directly from continental Europe were able to.

His uncle Jakub’s farm provided far more interest to the nine-year-old than pencils and books and Michael soon made himself useful there. He was barely 12 when he joined a group of men felling an area of bush on the outskirts of Stratford.

“In those days, you didn’t have to go to school. He could sign his name but never learnt to read or write properly. He was in the forest with the men. He never had any childhood, my dad, he was always working.”

Michael’s brother, the Joseph who came to visit his parents, liked life in America and would have returned had it not been for their father’s sudden death while Joseph was in New Zealand.

According to his death certificate, John Kowalewski died of pneumonia and cardiac failure at Croydon Road, Huiroa, Midhirst, on 12 December 1896.11 It is not clear whether he died at his brother’s farm, or whether he had already bought a place of his own.

Joseph took it upon himself to look after his mother, who became known as Franceska, and married Pauline Duszyński (spelt Dusienski on the shipping list and Duschenski in New Zealand) in 1897.

Franceska Kowalewski. The stratford evening post reported her death, aged 82, on 6 March 1923.

Michael was 13 when his father died. He joined blacksmith Robert Hancock in Tariki as an apprentice.

“That was an important trade in those days and he loved it.”

Michael married Clara Schumacher on 28 January 1907. He became naturalised in Tariki a year later, his occupation—blacksmith.

“But his family told him, ‘You’re married now, Mick, you’d better work on a farm.’ And he did. My eldest brother and sister were born on that farm in Tariki, but dad always wanted to go back to the blacksmith trade. He loved the horses. He could talk to them. He was only a short man but he was so strong.

“He didn’t like farming. One day, before Clem was born, he heard about a blacksmith’s job in [Stratford]. There was an opening and he took it.

“He went home and said to mum, ‘Come on, we’re going to pack up. We’re going to live in town.’”

Clara did not need much convincing. Her mother, Julia Schumacher (née Uhlenberg) had moved out of the family farm once her youngest son, another Joseph, married in 1916. Julia bought a house in Hamlet Street, Stratford, and moved in with her her then unmarried daughter, Annie. (Annie married John Habowski in 1919.)

“There was another house almost finished next door and dad said, ‘We’ll buy that one so you can look after your mother when she gets old.’

Michael and Clara moved in with Conrad (born in 1910) and Monica (born in 1912 and known as Mona). Clement, Leonard and Therese Kowalewski were born in the Hamlet Street house in 1917, 1920 and 1923.

This studio photograph was taken circa 1926. Mona and Conrad stand at the back Clement and Leonard flank their parents. Therese is in front.

“It was all bush and Clem—he was about 10 or 11—couldn’t get home from school quick enough to cut down a tree before dad came home and then they’d saw it up and drag it back to the house. I’d help. I might have only been a little kid but we never got hurt. Clem used a saw for the tree and an axe to cut off the branches and bit by bit, we cleared the section.

“The road was bracken fern. There seemed to be children everywhere and we all played together, no trouble. We loved playing in the bracken, making houses, until they cleared it and put down metal.

“I had a very happy childhood. I’d have it all over again. We had no conveniences. We boiled up the copper on the fire for the clothes. We had electric light but we didn’t have a [vacuum cleaner] or washing machine or deep freeze. We didn’t miss any of it because we didn’t have it.

Conrad stands at the back with his parents, Clara and Michael. In front are, from left, Therese, Clement and Leonard. The photograph was probably taken by Mona in the front garden of their Hamlet Street home.

“I can remember the first wireless coming in our street, just across the road from our home. This would be in about ’28 or ’29… my mother was going to town—we had to walk everywhere—and before she left, she said, ‘Mr Lindoff’s got a wireless.’ There was a big hedge around his house and all us kids, all lying under that hedge, we never moved. All we heard was music and static but we never moved. If anybody spoke, they got ‘Shhhh!’ For once we didn’t get into trouble.

“‘Oh mum, buy us a wireless…’ and mum said, ‘I’ll never have one of those noisy things in the house.’

“I can’t remember how long it was after that, but my sister—she wasn’t married then—she worked in town, and her boyfriend worked in one of those vegetable shops. They brought home this wireless in half a dozen pieces. It was a big set. There was the body part, and a huge loudspeaker… then Clement carried in two old car batteries.

“My sister’s friends set it up. I asked Len, ‘Why two batteries?’ He said one was a recharger. Still, they couldn’t turn it on because they had to set up the aerial. Now, the aerial, it was a six-foot pole with a wire at the top. They had to put that up, the farther away the better… and of course, the wireless was only on for a couple of hours a day back then and we could only get one station, 2YA Wellington.

“Mum loved listening to the races. It must have been not long before Christmas because they had a children’s programme on, aunt molly. She told us, ‘If you’re very, very good, Santa Claus will come,’ and we were very good, and on your birthday, they would wish us a happy birthday and say things like, ‘There’s a present for you in the sitting room behind the cushion or in the cupboard.’ You’d know your mother put it there and had written to them but it was such a novelty.

“Uncle Jasper was another announcer and later on they had Aunt Daisy. She’d say, ‘Good morning, good morning!’ They were lovely programmes. We used to listen to dad and dave and the japanese houseboy,12 radio plays and lovely serials.

“We used to have a horse and cart, a gig you’d sit in, and then my dad was the first to get a motor car, not the first in Stratford, just our road.

“Before my time Midhirst was going to be the town, not Stratford. They called Stratford a God-forsaken dump, full of mud, but then they cleared the roads and now look at it.

“My dad got a blacksmith’s shop of his own. The building is still there in Page Street next to the hotel. Dad was a blacksmith until he got cancer and had to give it up. He was only 69 when he died in 1952, two days after his birthday.

“I loved winter as a little girl because dad had to stop working when it got dark and we’d have tea early and mum would read the paper to dad while we washed the dishes and tidied up. Then we’d either play cards or have a sing-song.

“It’s all changed now and when people say today, ‘Oh how boring, no TV?’ I say, ‘We didn’t need it.’ On a Saturday, we could go to what we called the flicks, the pictures. There was always a matinee for the children with someone like Shirley Temple. Sixpence to go in and if we were very good, we were given another sixpence to buy ice-cream and a bag of lollies. We didn’t need holiday programmes like they have today. We loved holidays. We made our own fun.

_______________

Therese adored the company of her grandmother Julia, who hummed Polish hymns as she worked in her garden.

Julia arrived in Wellington on 26 July 1879 with her parents, Johann and Rosalia Uhlenberg, and five siblings. Her brother August, the one who married the two Marys Kowalewski, was the youngest in the family. Julia was 22. They travelled from Plymouth on the orari, whose 126 passengers were mostly British.

In 1882 Julia married Nicolaus Schumacher, a non-Catholic from Switzerland. They lived in Midhirst and had seven children, two of whom died as infants.

Julia appears on the 1893 Egmont electoral roll and no doubt cast her vote in the historic first vote for women on 28 November that year. Nicolaus did not vote. Fifteen days earlier, he left his family for an “overseas trip from which he failed to return.”13

Julia continued to farm alone on a property they had bought in Midhirst only two years prior. August delivered her milk to the dairy factory until her sons grew strong enough to manage. After seven years, courts officially presumed Nicolaus dead.14

For Julia, the move to Stratford meant a shorter distance to walk to Mass on Sundays. Until her death, aged 88, she remained an influential matriarch in the family and Therese in particular.

“I was a loner. By the time I came on the scene, the others had grown up. Being the baby, I had more toys than the others, a nice doll and a doll’s pram and I made daisy chains, decorations and mud pies. I could play by myself and enjoyed it.

“Sunday was visiting day. When I was little mum and dad would go to the Polish people in Inglewood mostly. I remember the names Bilski and Dravitski. The oldies played a lot of cards and us kids would play.

“I remember one time when Basia Bilski could not win anything. She was sitting close to the mirror and I think it was her husband who kept saying, ‘Mum, pick your hands up, I can see your cards. Hold your hands up.’ And of course she’d hold them up and he knew everything she had… Well, dad could see what he was doing and said, ‘Come on Basiu, you haven’t had very good luck, you and I will have to change chairs. She began winning and he said, ‘A change of chairs has brought you luck.’

“The first of June, the farmers would dry off their cows and have a party. The townies would all go. We liked going to Uncle Felix [Schumacher], mum’s brother, because he wasn’t fussy. They rolled up the carpet and we’d have a dance at his place in Beaconsfield Road [Midhirst]. My brother Clem was a musician, played the piano accordion by ear.”

Schumacher, Uhlenberg and Kowalewski relatives were always near but Therese remembers the camaraderie of the entire district during the war.

“Every road had a factory, a butter factory mostly, and there was always a hall. They’d have a farewell for soldiers going overseas or a welcome home for those who returned. The oldies would play cards and the young ones would dance. Everybody would bring something, a plate for the supper or some contribution. Everything seemed so much simpler then.”

_______________

The Great Depression would have left less of an impact on Therese had it not been for a letter addressed to “Michael Kowalewski, Blacksmith, New Zealand.”

“By then Len and I were the only ones living at home—my older brothers and sister had already married. We would be washing the dishes and clearing up and, as usual, mum would be reading the newspaper to dad, and then any letters. And so we got to know things.

“I remember that letter. How it got to us, I don’t know, but it was from Frank in Germany, the brother who went into the Prussian army.

“Mum read the letter. This was before the war, in the slump. Times were hard here but in Germany, it was worse still. Europe was in a bad way. The letter said something like, ‘Could you help us? We are starving.’

“I can remember dad saying, ‘We have to help.’

“My mother was fluent in German and Polish and used to do the translating in Stratford during elections for Bob Masters, the Liberal MP. It was before Micky Savage got in in 1935. There were so many foreigners here back then. They couldn’t read or write English and mum used to translate for them. She never learnt officially but she could make herself understood in other languages, like Lithuanian.”

“Thanks to mum’s job with the parliamentarian, they worked out how to send the money to dad’s brother. I don’t know how much, or if they heard from him again.”

Franz and Pauline Kowalewski had 10 children in Germany, four of whom died in infancy. Franz became a steelworker in an assembly factory in Friemersheim, Rheinhausen and died on 22 November 1928, soon after developing cancer. His obituary describes the “diligence, industriousness” and “dutifulness” of a “conscientious public servant… loving spouse and devoted father.”15

_______________

Therese’s oldest brother, Conrad, joined the Stratford Fire Brigade as a 14-year-old. He worked as a messenger until he was 17 and old enough to become a fireman. After two years, he left to do a compositor’s apprenticeship at the stratford evening post but that position became precarious during the Depression. The paper was sold in 1930 and Conrad lost his job. He had recently married Edna Myrtle Symons and they were expecting their first child.

“There was no welfare in those days but my uncle Joe Schumacher had two farms, one on York Road with an old house on it. Joe said, ‘Con, you can live in the house, we’ll clean it up… I’ve got no money to pay you but if you milk the cows, you can have as much milk as you like. You’ve got the land to grow vegetables and there are plenty of trees to cut down for firewood.’

“And that’s how they survived the Depression. The government wanted people to work on the road, 10 shillings a day Con said, and that’s the way he got a bit of pocket money. Otherwise, he had no money.

“In those days we had to help ourselves and people used to be good… We had a cow, mum had a big garden and we’d share. We’d give someone vegetables and they’d give us something else. We’d make our own butter and give away any extra milk. I never ever felt the poverty that people were talking about because I was a child. I never knew it. We always had plenty to eat, nothing flash but we were never hungry.”

Conrad moved his family to Te Awamutu to take up another farming job. The Depression eased and when he heard about an opening at the te awamutu courier, he pursued his career in the printing industry. He worked for the daily news and the taranaki herald and when Taranaki Newspapers Ltd formed in 1962, he became its commercial printing division’s sales representative.16 He died in November 1972.

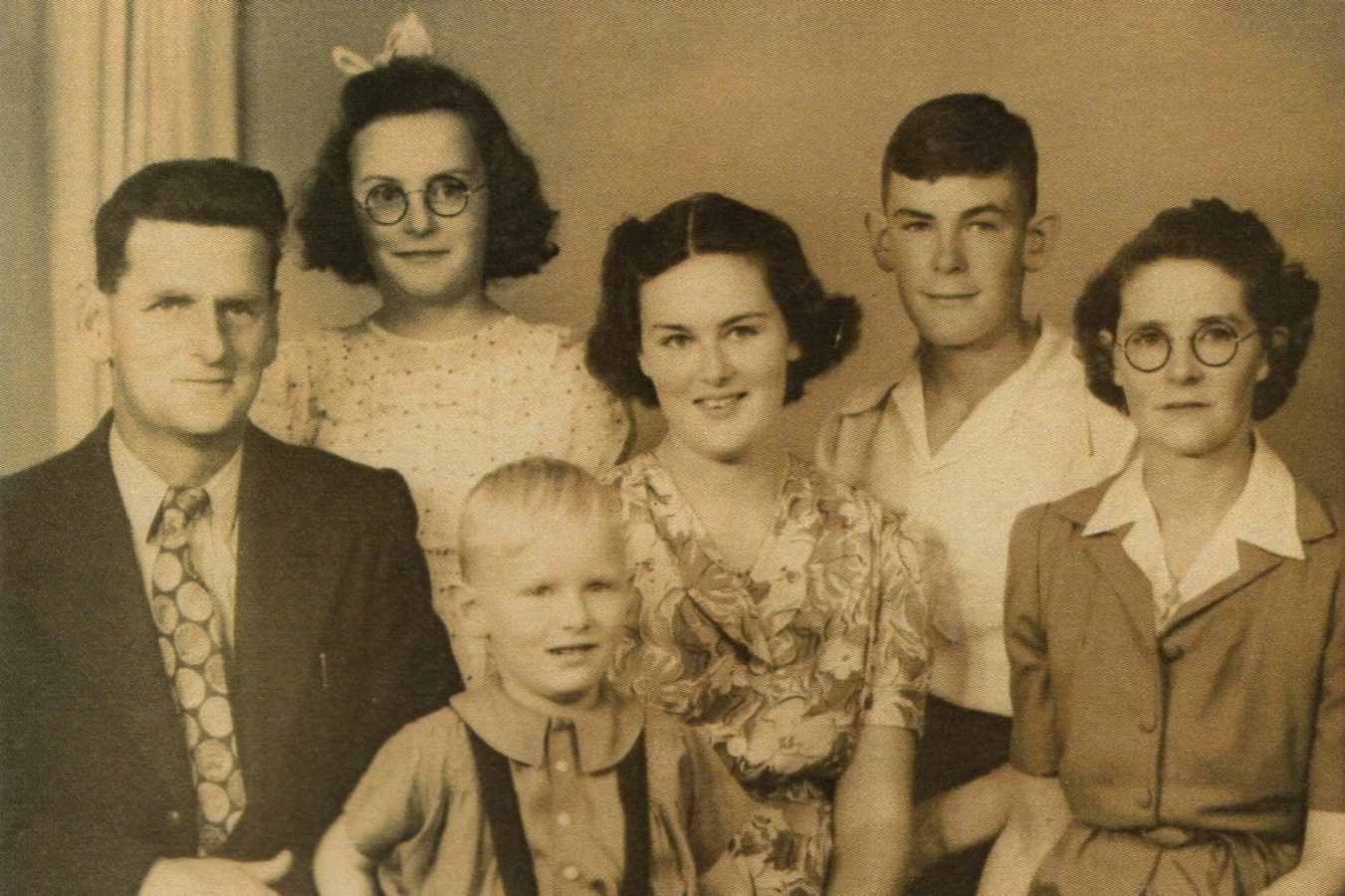

Conrad and Edna Kowalewski with their children, back from left Cecelia, Frances and Peter. Leon is in front.

When Leonard left school, he worked for Penny’s Grocery Store, which promoted free deliveries in Stratford. The boys who made the promise happen pedalled their fully laden bikes all around Stratford. When Conrad needed help on his farm, his younger brother obliged. Once no longer needed there, Leonard found work at the Oil Boring Company in New Plymouth. Therese remembers when the company started dredging off the Taranaki coast and needed men.

War arrived and Leonard walked onto the Ohakea Air Base wanting to become a pilot.17 A bout of pneumonia as a child frustrated his efforts and he had to be content with ground duties throughout New Zealand and Norfolk Island. On discharge from the Air Force in October 1945, he was offered a military position in Auckland but chose to return to Stratford to help his father.

Leonard worked alongside Michael in his blacksmith’s shop and finally bought out the engineering division. His father concentrated on his beloved horses and their shoes.

“After the war, you couldn’t get iron or other basics for the business because it was all in short supply.”

Leonard Kowalewski married Katherine O’Callaghan in 1947. They had three daughters, Patricia, Therese and Maree.

The family at Patricia’s 21st birthday celebrations in January 1969.

“Len was trying to find a house. He lived with his mother-in-law and dad said he’d divide our place in half and Len built his own house on the family property.

“Len kept the shop when dad died but he wasn’t a blacksmith and he didn’t want to shoe horses, and it wasn’t necessary then. The shop became a wheelwright. Len did the ironwork for wagons. Now they sort the mail there.”

_______________

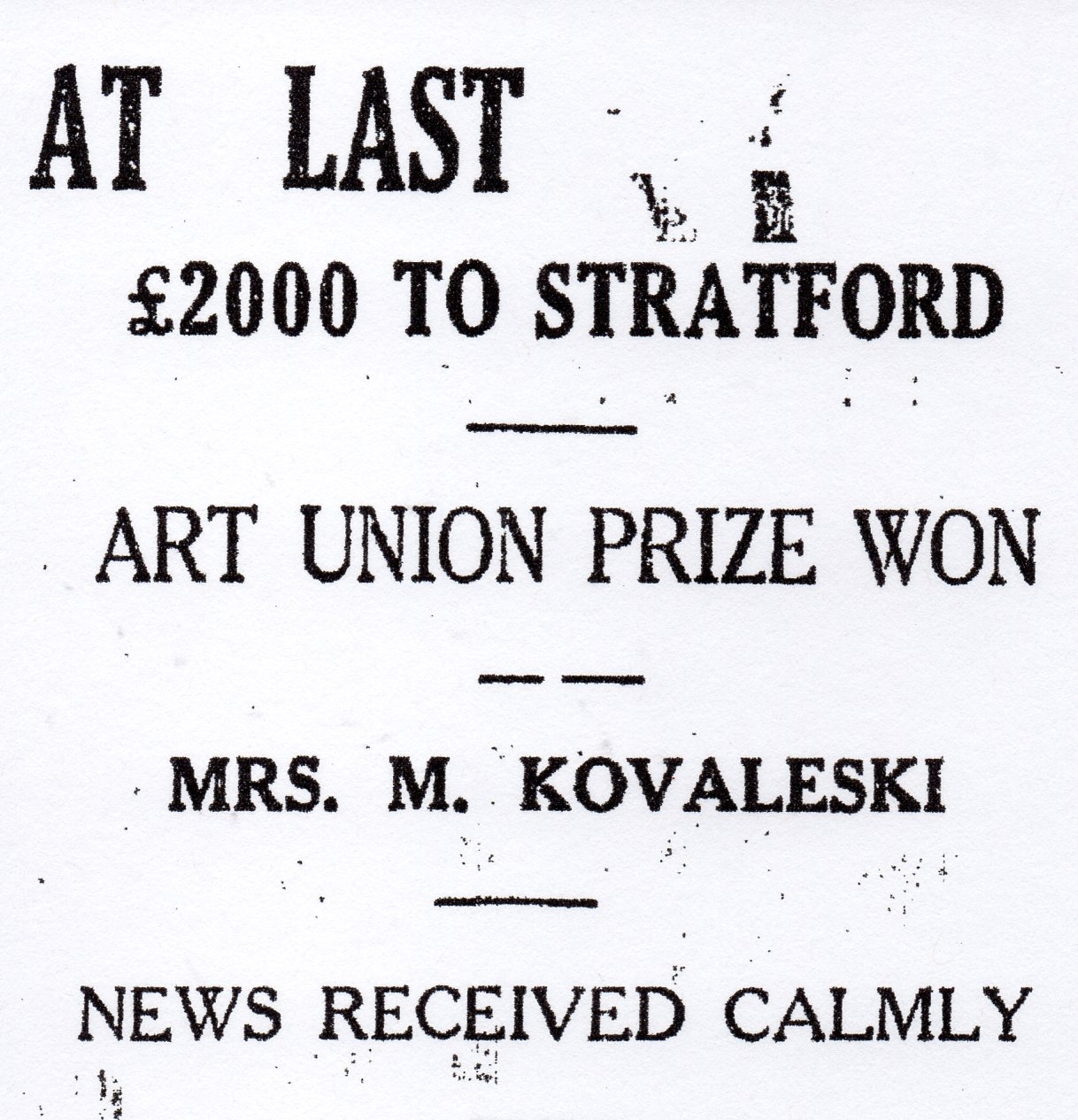

So read the headline at the top of page five in the stratford evening post on 16 April 1935, 10 weeks before the company that bought the newspaper after the Depression went into voluntary liquidation.

The story recited how on a wet evening Clara waited for her husband to give her a lift home in their car. Michael was seated at O’Keefe’s barber’s shop, waiting for a shave, when Clara noticed the coloured booklet of Art Union tickets. Although Michael complained he had “spent too many half-crowns on those things,” Clara convinced him that any extra cash would be useful, as they had just finished re-painting their house. She bought a ticket under the name “Paint.”

After the win, Michael told the newspaper: “… We can do with it… but of course we will carry on just the same.”18

And suiting action to the words he donned his canvas apron again and swung a heavy hammer lustily over his wheelwright’s anvil.

His children remember Michael saying: “The only luxury we will treat ourselves to is a fur coat each. Mum’s [has] the fur on the outside, mine the fur on the inside.”

This photograph of Michael Kowalewski was apparently taken outside his blacksmith’s forge the day he discovered that he and Clara had won the Art Union’s top prize in April 1935.

After the win, Michael helped Conrad with a deposit for his own farm. He again divided his section in Hamlet Street so that his elder daughter, Monica, who had married John William Hartley in 1932, could build a house and helped that young couple with its construction.

When her husband died in 1968, Monica repeated the gesture. Her eldest son, John, did not want the divided section next door, her second son, Michael, who worked in a bank, did not need it and it fell to her youngest son, Peter, to build a house and eventually become Therese’s neighbour. Monica died in March 1993.

The Schumacher-Kowalewski-Hartley houses in Hamlet Street, Stratford.

_______________

Michael Kowalewski’s ties to America emerged during World War 2, when two Polish marines bound for the Pacific detoured in New Zealand.

“One was dad’s nephew, the other his mate. Before he left America his nephew was told, ‘If you ever get stationed in Australia or New Zealand—they thought Australia and New Zealand were one—look up your relatives over there… Your uncle, he’s a blacksmith.’ They knew that but they didn’t know where he lived.

“They had leave and asked somebody, ‘Are there any Polish people here?’ They were told, ‘Go to Taranaki. That’s where the Poles are.’ So they got on a train that during the war stopped at Stratford. It didn’t go any farther. They got out, looked around and again asked somebody, ‘Are there any Polish people here?’ That person said, ‘Oh, yeah, the blacksmith down the road. He’s a Pole.’

“Dad was busy shoeing a horse, just like he always did, and this voice greeted him in Polish, ‘Hello uncle.’ Dad stopped, looked at these two Americans in uniform: ‘Who are you?’

“Dad said, ‘Just wait till I finish the horse.’

“They had two weeks’ holiday with us and I was the envy of all the girls in Stratford. We went everywhere, showed

them all we could. The nephew’s name was Joseph,

J-o-z-e-f he spelt it. I said I’d like to write to a sister or a

friend of theirs, be a pen-pal. I wrote to America for a while and then the letters stopped. I asked how the boys were

getting on and they wrote to tell me they were both killed on the islands. They never got back to America.”

It is not clear which branch of the Kowalewski family Józef came from. Michael’s sister Clara married a Jacob Leszkowski. She and her husband had six children.

This photograph of Clara (née Kowalewska) Leszowski with her husband and children taken at Stephany’s Studio in Chicago suggests she did not remain in Cleveland, Ohio

Michael’s brother Jakub seems to have disappeared but Johann junior, like Franz in Germany, worked in steel mills. He became known as John, married and remained in Cleveland. He and his wife, Augustine, had 10 children.

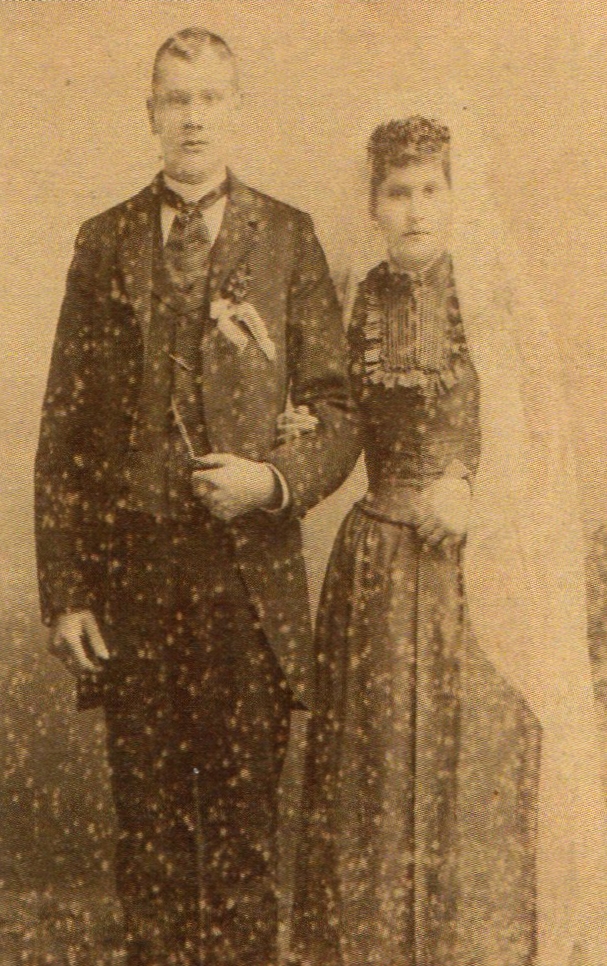

Johann and Augustine on their wedding day and about 40 years later. If anyone knows Augustine’s maiden name, please let us know through our get in touch page.

_______________

During the war, Clement did a tour of duty in the Pacific with the New Zealand army. Therese “man powered” at the Stratford Hospital.

“‘Man powered’ meant directed to essential work. I was sent to Stratford Hospital. I filled in on other workers’ days off, two days in the ward helping the nurses and feeding the very sick patients, two days in the kitchen and two days doing general cleaning jobs like mopping the floors.

“A couple of years later a vacancy came up in the hospital laundry. I applied and got the job. I loved it—regular hours—and stayed there until I went to the convent.

“When he came out of the army, [the government] allotted Clem a farm in Inglewood. He was making hay on the farm one day and put the grab through his knee. Len and I biked there from Stratford, milked the cows and biked back again twice a day, no problem. It’s what families did in those days.

“But he always wanted to be a market gardener and when the opportunity came, he sold the farm and went to Otahuhu in Auckland. He had huge glasshouses and grew tomatoes.”

Clement had honed his horticultural skills in Hamlet Street, where he built a glasshouse and dug up the family’s front lawn for a vegetable garden from which he sold much of his produce.

He married Anne Kuklinski in 1944 in Inglewood and died in August 1991.

Clement and Anne Kowalewski with their children, from left, Lawrence, Jennifer, Terence, Rosemary and Claire. Angela is inset.

_______________

Therese remembers the arrival of the Polish children to whom Prime Minister Peter Fraser gave refuge in 1944. (See the stories linked to our pahiatua refuge section on our war immigrants pages.)

“The children had adults with them and my mother and Aunty Annie and Uncle John [Chabowski/Habowski] went to see them. They could all make themselves understood with the Polish. There was Wanda Pietrasinska, and [Gizela] Sawlewicz with their families, and the Jania family. They stayed with us for holidays. The women were teachers and I remember Wanda visited quite often.

“The three girls, Halina and Danuta [Sawlewicz] and Maria [Jania] would never let their mothers stray too far from them.

“We had to be a bit careful during the war. We didn’t want people to think we were aliens.

“Our language was a mixture of everything. At home we called the sharp knife ‘kusi’ and the dishcloth ‘waslapen’ but I didn’t know they weren’t English words. When I was in Form 1 and 2, we used to have cooking classes and when I asked someone to pass me the ‘kusi’ they looked at me strangely.

“I went home and told mum and she said, ‘That’s not English, dear.’

“My mother was one of the first pupils at the convent school in Stratford. She was a senior. They learnt handwork and art and all those highfalutin subjects. We all went to the same school.”

Being the youngest of the family meant that Therese had her fair share of babysitting. She has fond memories of “kind of bringing up” Monica’s elder children, John, Margaret, Michael and Kathleen.

Monica Kowalewski married John Hartley in 1932. This photograph was taken in 1963. Seated next to their parents are Kathleen, left, and Margaret. At the back are, from left, Michael, John junior and Peter.

“Mum would say, ‘Mona’s not too well today, bring the children over to our place,’ and I'd fetch them and later I’d go to their home and help look after them. On Sundays I’d take them to the park to feed the ducks. I loved my nieces and nephews. I kept asking mum to buy another baby. I said I didn’t mind a boy or a girl.”

_______________

Therese had a calling to the religious order but did not want to leave her grandmother. Julia died in 1944 and Therese entered the training convent in Christchurch in January 1946. Three years later, she professed her vows as Sister Mary St Anselm and filled teaching positions throughout the North Island.

“I loved it but of course education changed and I can’t make head or tail of it now. In those days, you could teach as long as you were studying for a teacher’s exam. You didn’t have to go to university. I taught in Ngaruawahia, Huntly, Opotiki, Eltham, which was very nice, Waitara, Papakura and Kaponga.

“I started with the primers, the beginners, and I finished as head teacher in Kaponga, with Forms 1 and 2.

“In those days we did everything. With the convent school, we never had cleaners. We never had secretaries. We did it all and it was lovely. Those were the good days. We did everything ourselves.”

Therese’s primer class sizes ranged from 40 to 45 in rural Ngaruawahia, “lovely children, there’d be no problems,” and she later coped with classes the same size in Auckland’s then up-market Papakura, which had newly opened as a convent school when Therese joined the staff. She watched the three original rooms expand to six by the time she left.

“Papakura was lovely but I liked the little country places. I’m a country girl at heart. I loved Ngaruawahia and then I finished in Kaponga, just down the road from Eltham. I was in Kaponga for 13 years and retired from there.”

Therese with two of her Kowalewski cousins, Agnes Keegan and Veronica, who took the name Sr Gertrude, on the occasion of Sr Gertrude’s silver jubilee in 1974.

Sister Anselm taught her classes more than the three Rs. She subtly instilled into her pupils her lessons in fairness and basic humanity by making sure every one of her pupils had the chance to practise leadership.

“There were times when I had to leave somebody in charge and to answer the phone. I said I would do it in alphabetical order. Once someone had their chance, they would go to the back of the queue.

“Along came a boy as rough as a diamond. I was slightly worried and got someone to phone the school: ‘Good afternoon, St Patrick’s School,’ the voice answered. He was perfect!”

Therese retired from teaching in 1985 and has been living in the family home since then.

These days gardening remains a joy, as does her extended family. Therese has no time to be lonely with her nephew Peter living next door, and nieces and nephews regularly calling in person or on the telephone.

“Next door, they’re very good to me. The Lord has been good to me. I’m not what you would call a social person. I don’t mind my own company. I’m no good in a crowd. I am deaf but I don’t miss much.”

“When I first came here I had a lot of people visiting. They would phone and say, ‘I’ve just baked a cake. Put the kettle on,’ or ‘Is the kettle boiling? Our electricity has just gone off.’ We never stood on our dignity and I was lucky.

“My brother Len was still on the other side when I came here in 1985. It was the year his wife died and that brought us closer together. We were still independent but we became very close.

“I can see it all in my mind, but you’ve got to remember, it’s from my point of view. People think, see things differently, remember things differently. After Leonard’s wife died, he’d come over from next door and we’d be sitting here and start talking. We both had different memories about the same thing. His came from a man’s point of view and I suppose mine came from a woman’s point.”

Leonard Kowalewski died in October 2005.

Therese’s garden continues to supplement her meals—except breakfast, which is the same every day: a Marmite sandwich, five dates, and coffee made “on milk.”

At 94, Therese has never complained about having nothing to do.

“I’ve never been bored. Never. I just go out into the garden and I’m busy.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2018

APART FROM THE FIRST PHOTOGRAPH, ALL FAMILY PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY THE KOWALEWSKI FAMILY BOOK COMPILED BY MARY DETTLING AND ORIGINALLY FROM THE KOWALEWSKI COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Mary Dettling, KOWALEWSKI FAMILY TREE

1871 Joseph Kowalewki = Pauline Duschenski

1873 Mary Kowalewski = Augustus Uhlenberg

1883 Michael Kowalewski = Clara Schumacher, page 7, 2015. - 2 - Wilbur E Gray, Prussia and the Evolution of the Reserve Army: A Forgotten Lesson of History, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 1992, page 10. Unclassified June 1986.

- 3 - Spelling on the Palmerston passenger list.

- 4 - Off the Lamershagen.

- 5 - Family book, page 5.

- 6 - Family book, pages 38 & 39.

- 7 - A copy of the passenger list is in the family book, page 18.

- 8 - State Records Authority of New South Wales: Shipping Master's Office; Passengers Arriving

1855 - 1922; NRS13278, [X163] reel 457. Transcribed by Barry Collin.

http://marinersandships.com.au/1893/03/044oro.htm - 9 - Family book, page 232.

- 10 - Family book, page 237.

- 11 - Family book, page 34.

- 12 - RNZ, Theatre of the Mind: The story of drama and serials lists some of the early serials

and dramas that New Zealanders heard on the radio from 1928.

https://www.radionz.co.nz/collections/resounding-radio/audio/2593912/theatre-of-the-mind-the-story-of-drama-and-serials - 13 - JW Pobóg-Jaworowski, History of the Polish Settlers in New Zealand, 1776-1987, page 87, CHZ “Ars Polona,” Warsaw, 1990.

- 14 - Ibid.

- 15 - Family book, page 227.

- 16 - Family book, page 332.

- 17 - Family book, page 400.

- 18 - Stratford Evening Post, 16 April 1935, page 5, AT LAST ₤2000 TO STRATFORD,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/STEP19350416.2.30