UNDER THE MOUNTAIN

LAYERS IN THE MILLE-FEUILLE OF TARANAKI HISTORY

First meetings with descendants of Polish settlers in Taranaki tend to include the words, “It’s complicated.” They are right.

The Poles in Taranaki made up the largest single group of early Polish settlers in New Zealand. Many arrived on the same ship, the fritz reuter, but they did not arrive in the area at the same time. They often married other Poles, and why wouldn’t they? Marriages happen among people who know one another and, especially in the early years, the Poles socialised with those they knew and understood.

The lengthening lists of marriages upon marriages, births upon births, and deaths upon deaths, would have kept this story in my To Do basket had it not been for a 1991 newspaper clipping I found in one of the late Florinda Lambert’s Green Books at the Puke Ariki research centre in New Plymouth: exotic tongues in the taranaki bush recalled 150 years since the arrival of the first settlers from Devon and Cornwall—and listed the names and ages of the Polish arrivals in 1876.

The same research centre holds the ration books that contain the names of those who stayed at the immigration barracks on Marsland Hill, including the eight Polish families who in 1876 walked north up Devon Street out of New Plymouth, and inland into Inglewood, and who became the core of this story. Many more Poles settled in and around Inglewood, Tariki, Ratipiko, Midhirst, and Stratford, but these eight were the first.

Florrie, as Florinda was known, accumulated 11 volumes of newspaper clippings, invaluable, as several of the local Taranaki newspapers are not yet digitised. She descends from Felix Voitrekovsky (Feliks Wojciechowski), whose family story is on this page.1

As usual with my stories of early settlers, I made extensive use of papers past, a mighty resource that has digitised hundreds of newspapers and publications during their many years of publication. They help answer the researcher’s constant question: Why? The articles revealed the new colony’s sluggish attitude towards helping continental European settlers such as the Poles, and its voracity in embracing English ones.

Official documents of the time spelt Polish names in many random ways. Some germanised Polish names evolved into anglicised versions, and some names disappeared into the quicksand of New Zealand’s Births, Marriages, and Deaths (BDM).2 I followed spellings most often used by families.

Through their illiteracy and original lack of the English language, the early Polish settlers in Taranaki missed the tensions between Māori and the British colonists that lingered in the area after the 1860s Taranaki Wars. By the time the Poles’ New Zealand-born sons joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces during the Boer War and WWI, however, they well-understood discrimination.

This is the bite I have taken out of the mille-feuille of Polish history in Taranaki. I know I have left bits of pastry and crumbs on the plate. I will pick them up later.

Thanks again to Ray Watembach, who pored over the ration books with me, gave me his transcribed list of Joseph Fabish’s early Polish births, deaths and marriages, and who guided me on aspects of the 1996 Waitangi tribunal on Taranaki; to Sr Mary St Martha Szymanska, who, rightly, insisted on the headings, which created the visual layers; to Joan Dickson, for being one of the first people to trust me with me a copy of her Uhlenberg family book in 2013, and allowing me to use it; to Paul Klemick for doggedly finding Lucia Myszewska; and to the librarians at Puke Ariki and Inglewood.

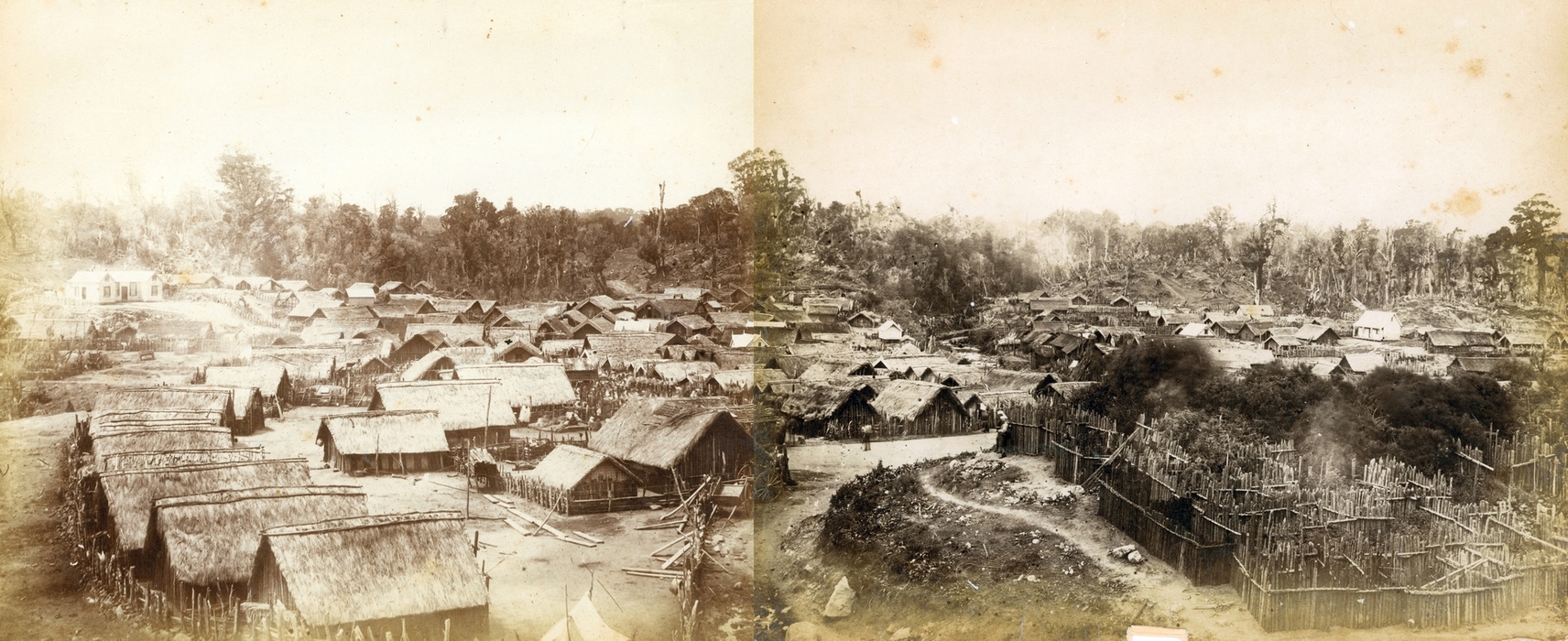

The image above is Inglewood in 1874, five months after the arrival of the surveyors and “advance party.” The few huts scattered among the piles of felled trees are partially hidden by the smoke.3

—Barbara Scrivens

THE FIRST EIGHT POLISH FAMILIES

On 6 September 1876, seven married couples, a 26-year-old man, and a 13-year-old classified as a statute adult, took their first steps towards Inglewood and what was to become the largest and most enduring settlement of Poles in New Zealand.

They walked out of the immigration barracks on New Plymouth’s Marsland Hill, down the hill that led to the beach and the main township, and turned up the coast towards Waitara. They carried their bundled possessions, and no doubt the youngest of their eight children aged between 18 months and nine years. Barbara Dusienski was seven months’ pregnant. Fresh from receiving rations at the immigration barracks, it is unlikely that they had money to spend on hiring a horse and dray for those first several kilometres—the only part of the Taranaki coast then that resembled a proper road.

They were used to walking. Knowing that they had no future in their homeland, most had walked much of the average 800 kilometres from their homes in Prussian-partitioned northwest Poland to the port of Hamburg. In April 1876, they boarded the fritz reuter, the last ship to bring a substantial number of immigrants from continental Europe to New Zealand.4

Their first steps in Taranaki must have been buoyed by the promise of employment at their destinations—at least one family stopped at Bell Block—and the relief of having escaped from the increasing persecution they suffered for their nationality and religion after the French lost the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War, and Otto von Bismarck grew in power. As Chancellor for German Emperor William I, who established a new monarchy in 1871, Bismarck forbade any practice of Catholicism, or Polish teachings.

Poles like those off the fritz reuter had been labourers at the mercy of German employers who felt no obligation towards them. Before Poland’s third partitioning by the Prussian, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian Empires in 1795, most had been serfs attached to noble families, or worked for wealthy land-owners.

Many of those who owned a small piece of land at the time of the Franco-Prussian War, had it swindled from them. Several of the first Polish families tell stories of how the Poles handed the deeds to their land to wealthy neighbouring German farmers “to keep” for the duration of the war, after the Germans offered them work in the fields, rather than going to war on the Prussian side and risk fighting against Poles they knew were on the French side. The deal made sense—war or no war, people still needed food—but once the war ended, the Germans did not return the Poles’ land deeds.

Birth records from different villages in north-western Poland confirm that Polish families moved from town to town to seek work, so the instruction by New Zealand immigration agents to get to a certain place at a certain time could not have worried them.

The fritz reuter arrived in Wellington harbour on 4 August 1876 after 118 days at sea. At least four children and six babies died during the voyage,5 including three infants from the New Plymouth group.

At first, New Zealand immigration authorities prevented the fritz reuter passengers from disembarking—they disputed their legality as immigrants.6 Authorities eventually allowed them into the Wellington immigration barracks, where many of the single men, single women, and childless couples quickly found employment. A former immigration agent, Arthur Halcombe, requested immigrants for the Mānawatu-Rangitikei region, and 89 (65½ statute adults) went with him to what was known as the Manchester Block near Fielding. Another group went to Hokitika and Jackson’s Bay (now Jackson Bay), on the South Island’s remote west coast.

Those who landed in New Plymouth on 16 August 1876, moved into the town’s refurbished immigration barracks on Marsland Hill. The buildings were formerly military barracks used in the 1860s Taranaki Wars.

BEFORE 1876

Surveyor Edwin Stanley Brookes, who arrived in New Plymouth in 1874, noted that “mementoes of the war between the races [met] one at every turn.”7

British troops first arrived in New Plymouth in 1855, as protection for its settlers, deemed vulnerable to Māori attack following the colony’s questionable land deals. During the Taranaki Wars, initiated over the sale and confiscation of land, at least 20 new military settlements, stockades, redoubts, and outposts scattered the Taranaki coastline—a sign that civilian Pākehā settlement existed for strategic military purposes.

The rumours of Māori attack were just that—rumours. British politicians running the colony needed to create a war, to fabricate a reason for confiscating Māori land as punishment for rebellion against the Crown. The ploy had its precedent in feudal times, and the English also used it in the 1700s in Scotland and Ireland. The New Zealand government legalised its confiscation of Māori land through three 1863 pieces of legislation: the New Zealand Loan Act, which allowed the “profitable sale of confiscated land to pay the costs of colonisation,”8 the New Zealand Settlements Act, which provided for the confiscation of Māori land, and the Suppression of Rebellion Act.

In 1996, the Waitangi Tribunal, in its taranaki report; kaupapa tuatahi, declared that the confiscations were unlawful on several grounds: They did not comply with the New Zealand Settlements Act; they were carried out without sufficient evidence of Māori rebellion; and there was no “proper regard for the statutory purpose of achieving peace.”9

If the Poles who arrived in 1876 had been able to read English, they may have paused at some of the war “mementoes” that Brookes mentioned. The Poles were familiar with the Prussian army. Its conscription and reservist system had secretly accumulated enough men to overpower the French in 1871. Aged 20, men living in the Prussian-partition of Poland spent three years in military service, then another two in the reserve force, and a further 14 in a stand-by force. Few could escape its strict rules, which is why so many Polish children had their births registered near towns with military garrisons.

AUGUST 1876

The taranaki herald published a story on 16 August 1876 about 52 “German [sic] immigrants” who were expected to land in New Plymouth off the ss taupo from Wellington.10

The beauty of the return of the free rations issued daily to immigrants at immigration depot new plymouth at the Puke Ariki museum is that it holds a more accurate record of the people who stayed there: their names, the dates they arrived and left, and the number of rations given, and for whom. It shows, for instance, that on 16 August, 56 people arrived at the barracks—16 single men, three single women, 11 married couples, one father and daughter, the 13-year-old, five boys, six girls, and a baby boy.

The immigration depot’s return confirmed that three infants who embarked with their families on the fritz reuter in Hamburg were not at Marsland Hill. It was as much of a death notice as they were going to get.

The Poles in the barracks were:

—Paul (34) and Marianna née Krygel Biesiek (37), whose 22-month-old daughter, Maria, died at sea;

—Mathias (31) and Apolonia née Drozkowska Dodunski (26), with their children Franciszka (7) and Franciszek (2);

—Joseph (25) and Barbara née Drozdowska Dusienski (22);

—Johann (41) and Carolina née Funk Myszewski (22), with Johann’s children, Julianna (15), Jacob (13) Catharine (9) and Josef (6). Their 18-month-old daughter, Franciszka, died at sea;

—Lucia (24) and Johanna (19) Myszewski;

—August (26) and Apolonia née Potroz Neustrowski (26), and their children Marianna (4) and Johan (2). Their seven-month-old son, August, died at sea;

—Anton (24) and Josephina née Funk Potroz (25), with two-year-old Jakob;

—Franz Uhlenberg (26, but 33 on the passenger list);

—August (25) and Emilie Marie née Eichstaedt Volzke (22), and their 18-month-old son, Carl Frederick Albert (the ship’s passenger list named him Auguste).

Among the first “engaged” were the single, orphaned sisters Lucia and Johanna Myszewska, and their cousin, Julianna. The return shows that Johanna and Julianna were employed on 19 August, and Lucia three days later. Three of the single men were also employed within days, as were the father (54) and daughter (16), and two married couples, each with a child. The return does not say who employed them, or where they went.

Eight married couples, the remaining 12 single men, and 13-year-old Jacob Myszewski were employed on 5 September 1876. Rations stopped for them, and the 10 children on 4 September, the day that the taranaki herald wrote that 17 of the immigrants “started for Inglewood” to work on “logging and otherwise preparing the Mountain Road for the extension of the railroad beyond Inglewood.”11

A farmer Rundle employed August Neustrowski, to clear his land of furze (aruhe) in the Bell Block. The family was still living there when Agnes Neustrowski was born at the Hua village in April 1877. Rundle would probably have employed more than one person to do the work, so it is feasible that others joined the Neustrowskis.

The Poles left one family behind. Frederyk Trebes (29)12 was admitted to the provincial hospital on 31 August 1876. Wilhelmina Trebes (30) remained at the barracks with two-year-old Anna, and Otto, who was born at sea. Frederyk returned on 15 September but, according to the ration book, was readmitted to the hospital on 9 October, when his family was the only one left at the barracks.

A note in the return’s Remarks column written by the Depot Master, G H Herbert:

“Wife & family struck off rations after the 31st [October].”

Striking off a mother with an infant daughter and baby without as much as a forwarding address or assurance of their future welfare, suggests that Herbert held a callous disregard for immigrants whom he decided had overstayed their welcome—in stark contrast to the reception received by passengers who arrived at New Plymouth the year before off the halcione from Gravesend:

On arrival all the immigrants were given a royal reception and well looked after until they left for Inglewood.13

The stormy seas off the New Plymouth coast often made it dangerous to transfer passengers, but in 1875, 21 single women, and 14 families, including one from Switzerland, made it off the halcione at first attempt. Four of the families went to friends and the rest to Marsland Hill.14 The other 189 passengers returned to Wellington and came back a few days later, when New Plymouth dignitaries led by the Archdeacon Govett treated them all to a public tea. The speeches, readings, songs, and piano and accordion renditions lasted into the evening.15

The generosity of the colonial government did not seem to extend to those who did not speak English. On 28 December 1878, the weekly taranaki news wrote about Franceszka Kurowska, one of the fritz reuter passengers. In November 1876, she, her husband and four children were the last Poles to settle in Jackson’s Bay:

A German [sic] widow with four children and near confinement, is at Marsland Hill Immigration Barracks, destitute; she is off rations. Her husband was drowned, and, as all her country people left Jackson’s Bay, she availed herself of the offer of the Government steamer, and came away. She has the offer of an immigrant cottage, but has not had the means to buy a little furniture to put in it, to make herself and her children a little comfortable. Mr Weyergang has kindly consented to receive donations for this poor person.16

The Poles who walked out of New Plymouth two years earlier, would have have crossed Devon Road’s wooden bridge over the Huatoki stream. The road, just wide enough for a horse and dray, had been metalled “a few feet wide” along the centre.17 They may not have paid much attention to war memorials or plaques they could not read, but the new settlers could not have failed to notice that the quality of the road fell far short of what they were used to in central Europe. They may have been oblivious to the military tensions in Taranaki, but they soon adapted to the area’s natural hazards.

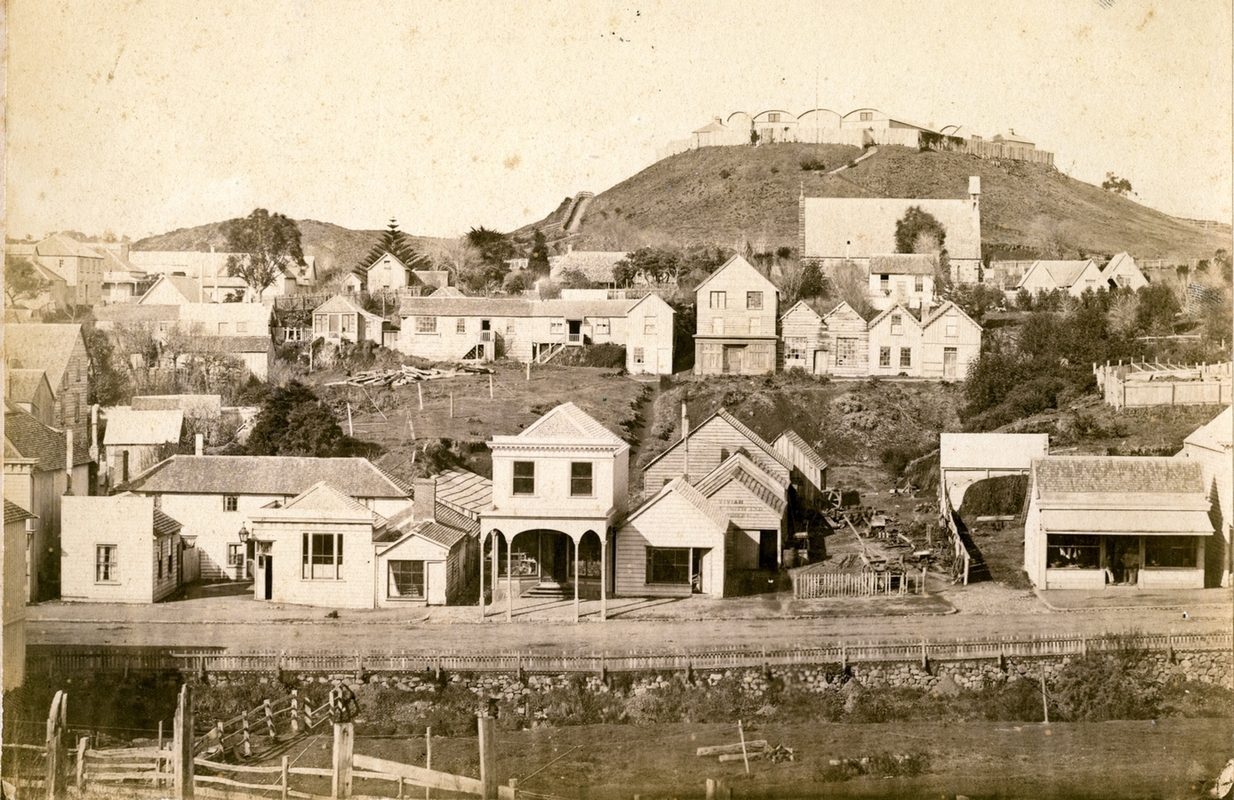

Taken in 1875, this photograph shows Devon Street in the foreground looking towards Marsland Hill barracks. The large structure at the base of the hill is St Mary’s Anglican Church, now the Taranaki Cathedral Church of St Mary. (Photo: Puke Ariki –1)

Then, Mountain Road was still the only inland route that the colonists used, accessed from Sentry Hill about 12 kilometres north of New Plymouth. (A more direct route was created later, through Egmont Village along what became Junction Road.) Even if the group had hired a horse and dray to help them, once they turned inland at Sentry Hill, that transport would have soon bogged down in the moist, early spring.

More of an aspirational road than a useful track, Mountain Road had been cut at a chain’s width,18 through dense bush that blocked out sunlight. The road took the runoff from Mount Taranaki (then Mount Egmont). For at least half the year, horses and carts became stuck in its mud, or slipped down its gullies, and people tended to walk holding their possessions or purchases.

TARANAKI BEFORE THE POLES ARRIVED

In January 1875, surveyor Brookes, armed with a plan of the Moa Block, led a group of British immigrants along Mountain ‘Road’ to Inglewood. They left their dray at a house at the end of the felled track, and transferred their portable belongings into swags:

Brookes: “It was hard work for the immigrants to carry their loads, as they were not used to rough bush roads, which, to tell the truth, were almost impassable for travellers.” One member of the party became lost, “… having at intervals dropped various parts of his clothing which, when found, proved he had been walking in a circle within a short distance of the road.”19

Brookes described the Mountain Road running in the direction of “General Chute’s track,” but more directly, and with a “better line.” In January 1866, General Trevor Chute, fresh from bloody skirmishes with Māori in south Taranaki, decided he would penetrate the forest below Mount Taranaki by following the Māori Whakaahurangi trail from Normanby to New Plymouth. Chute estimated his more than 500 soldiers, forest rangers, and pioneering units could break through in three days.

He missed the trail, misjudged the terrain, and underestimated the weather. Despite their numbers, equipment, and pack horses, Chute and his men took 10 “tortuous” days to get to the other side.20

On the first day, the soldiers “crossed four gullies, two considerable streams, and made about 9½ miles.”21 On the second day, the forest “became more dense and difficult of passage” and towards the Patea river, the gullies “became more numerous and deep.” They covered 13 miles, crossed the Patea, and scrambled through 13 gullies.

The six miles they covered on day three involved passing “one of the worst gullies yet met with and six rivers.”

Their rations ran out on the fourth day, but they crossed another 15 gullies and seven rivers and put 11 more miles behind them. Rain fell “in torrents” on a party sent ahead to procure more provisions. The exhausted and hungry men left in the bush could only manage four miles on the fifth day, but they crossed another 15 gullies and four rivers. That evening they killed a horse to eat.22

The soldiers woke on day six to “a quagmire” beneath them and “a constant shower of rain” above them. It became a rest day, with another horse killed for food.

On day seven—the third of rain—the men covered six miles in eight hours “wading deeply in mud,” and crossing 21 gullies and three rivers. That night they ate the fresh rations that arrived. They tramped four miles over ground still “soft and wet” on a “gloomy” day eight, but on day nine, they emerged from the forest after “five miles without a gully” and camped at Waiwahiko. They marched into New Plymouth on day 10.23

Apart from demonstrating that 500 soldiers could thrash through nearly 80 kilometres of bush behind a purpose-built track and with a reinforcement of rations, it is unclear what General Chute’s march accomplished for Taranaki.

Taranaki superintendent, an H R Robinson, greeted the general and his troops when they arrived in New Plymouth. Robinson seemed to think that Māori would be impressed that “British courage and British arms can penetrate wherever man can hide… and that the only course open for the hostile natives is frank submission to the just and equal law which the empire and the colony hold out for their acceptance.”24

Eight years later, surveyor Brookes arrived from Auckland on the steamer lady bird, aware that Taranaki was “was considered the hot-bed of the Māori rebellion, and the great difficulty of landing there made travellers inclined to give it a wide berth.”25

The tarnishing of Taranaki’s reputation was unfairly blamed on Māori, but it was Governor Thomas Gore Browne who in 1860 initiated military action against the local indigenous people. He “assumed his own authority must prevail and that of Māori be stamped out”26

Once the lady bird anchored with the surveyor Brookes, her captain blew his whistle to wake the boatmen on shore.

Brookes: “The surf was making a terrific noise at the time—a white line of rollers could be seen chasing one another to the beach, where they would break in one mass of white foam. It was for a time doubtful whether the surf-boat would be able to get off from the shore…

“The passengers were handed into the boat… you had to make a spring and a jump in when the boat rose on top of a huge wave… the rope was cast off… Then the men tugged at their oars and the boat swept along, riding the seas in a fair manner until coming to the breakers, when the spray gave us all a thorough drenching.”27

The town, founded by the Plymouth Company in 1841, gave Brookes the impression of being “essentially English,” which he ascribed to the more than 800 colonists from Devon and Cornwall.

The Poles arrived in Taranaki at a time when the man who laid out the town in 1841, Frederic Alonzo Carrington, was its provincial superintendent. Carrington had left New Zealand in 1843—after the New Zealand Company absorbed the Plymouth Company, which employed him, then cut his survey contracts, his materials, his wages, and finally, his job—but he never lost his love for that part of New Zealand, and returned with his family in 1857.

In 1841, Carrington had briefly toyed with laying out the town in Waitara, but the Waitara river’s shallow bar and rough seas changed his mind in favour of building a future harbour in the shelter of the Ngā Motu/ Sugar Loaf Islands off the New Plymouth coast. He knew that completing the transport link between the Taranaki south coast and a yet-to-be-built harbour was the only way to Taranaki’s prosperity. By 1873, he was becoming desperate for immigrants, and requested 150 early that year, but by 31 May 1874, Taranaki had received only 27, bringing its total number of immigrants under the Vogel scheme to 42.28

New Plymouth’s inability then to receive larger ships, and the New Zealand Company’s refusal to send its ships there, allowed Wellington to filter its immigrants. Few got through, and fewer stayed.

Despite Carrington’s championing for a harbour, it took until 1881 before he was able to lay the foundation stone for the New Plymouth breakwater, and the town waited another five years before overseas ships berthed alongside a finished structure.

Taranaki remained a largely unknown part of the colony. It was the last province to gain “substantial benefits from Vogel’s 1870 Public Works and Immigration Scheme.”29

THE MOA BLOCK BEFORE THE POLES ARRIVED...

Carrington managed to convince Sir Harry Atkinson, who had a reputation for not being able to resist a political fight,30 to take on the position as Taranaki’s provincial secretary for a few crucial months from May 1874. Atkinson convinced the colonial government to give Taranaki 110,000 acres of “new” land along the Mountain Road for two townships.

By September 1874, Atkinson had joined Vogel’s cabinet as Secretary for the Crown, and Minister for Immigration, but the promise of the new land was enough for Carrington to travel to Wellington in July 1874 and persuade 119 immigrants off the waikato to join him in New Plymouth. Two groups of men from the waikato reached the Moa Block after a “weary passage of four days,” made camp, and started felling. They joked about leaving England for such rough country, and most moved on to places where it was easier to make a living.31

New Plymouth residents seemed interested in Inglewood’s progress, and visitors inland kept the townsfolk seaside updated.

The writing on this photograph says, “Inglewood from recreation ground.” If the writer of te moa—100 years of inglewood history 1875–1975 is correct in suggesting it might have been taken from Trimble Park in 1875, this road would have been what was then known as the Junction Road, and later Rata Street. The double storey structure to the left of the background was probably the hotel, built by April 1875, and closer to what would have been Mountain Road and the railway line. (Photo: Puke Ariki –2)

A Mr Kenworthy had a friend who found Brookes in a “hut” on 13 January 1875 and was rewarded with a guided tour of potential land for sale. Kenworthy seemed impressed: “No mistake could be made by anyone purchasing, if anxious to get level and good agricultural land. The bush on it is light, with here and there large trees.”32

The trees in the background of the photograph show how dense and tall the raw bush was. Kenworthy’s description could only have referred to what was directly in front of him. By the time the 1876 Poles arrived, and had saved enough for deposits, the land on offer was exactly that raw bush.

Felling cleared the first 100 acres of the Moa Block around where Mountain and Junction road crossed, “although these roads hardly existed except in name.”33

A “party of gentlemen,” including 16 from the provincial council, rode to the Moa Block on 22 January 1875 to christen Inglewood with champagne, and rode out the same day. Superintendent Carrington missed the occasion as he was meeting the avalanche due in New Plymouth.34

Until then, the township had had several names, from Who’d a Thou’t It? and New Found Out, to Moa Town and Milton, the latter before the administrators found out that a Milton already existed in Otago.35

On the day of its christening, Inglewood’s only proper structure was a store. By April, another visitor counted about 20 inhabited “huts” and saw about 10 buildings, either erected or being built, including a two-storey hotel. There must have been several families, because the Taranaki Education Board called for tenders for a school. By October 1875, 60 children waited to attend the still-unbuilt facility.

No matter how good the land was, or how much work had been done clearing it, access remained a problem. Although a trip to Inglewood could take two hours on horseback in fine weather, in the wet, the Waiongana river was unfordable, and the road impassable.

The budget newspaper regularly reported on the muddy roads. In June 1875, it told of a man who drowned in the Maketawa river after his horse became entangled in tree roots. The river washed his body downstream to Waitara. And on 27 November 1875:

A traveller from Inglewood complains about the dreadful state of the roads between there and Town and the apathy shown by the authorities in regard to the matter. A horse which was being ridden along got stuck in the muddy road and he was near being drowned for want of assistance to extricate him.36

The ford at Maketawa river, circa 1875.37

… AND IN 1876

Taranaki County Council took over the Inglewood settlement in 1876, and Colonel Robert Trimble formed the first board in 1877. Trimble had taken up a considerable amount of land—2,100 acres in March 187638—much of which became as reserve. On Inglewood’s first anniversary, someone apparently climbed a hill now known as Trimble’s Walkway, and counted more than 120 buildings.

Two extracts from the budget in 1876:

On the Inglewood Road this week, an owner of Moa Block sections was seen hauling himself along the muddy roads beside a horse on which was a pack-saddle, on which was packed an strapped an almost innumerable variety of articles. There was tucker and cabbage plants, fruit trees and flowering plants. There were seeds of all descriptions, from peas to potatoes, and innumerable nick-nacks. To crown the lot, a young calf had been strapped on top of the load. It looked as if some people have faith in the future of the Inglewood district. Such perseverance and pertinacity in overcoming difficulties deserved a rich reward. Doing something is better than growling. (26 August 1876)

One day last week, four or five men went into a store at Inglewood for some pipes. While the storekeeper was away for change, the men saw some biscuits handy, and being tempted, partook. The biscuits, being tasty, were eaten with relish. All these men were much troubled during the night. They had but little rest. In fact they were in great pain. The biscuits of which they had so freely partaken, were worm biscuits, and were only intended to be eaten bits at a time by children. (2 October 1876)39

In 1876, the first Poles crossed the Waiongana river over a bridge built for Inglewood’s first anniversary. Those Poles and their children built many more bridges. Mathias and Apolonia Dodunski’s ninth child, Martha (who married Albert Schimanski in 1907), regaled her daughter Sister Mary St Martha Szymanska with her father’s decades of taking on bridge contracts, and later including his growing sons:

Sister St Martha: “At the completion of a bridge, they had their photograph taken. My mother had some lovely ones of her father and brothers in their waistcoats and hats and holding shovels. No one seems to have those photographs now.”

Even with today’s drainage, a current topographical map shows nine visible streams crossing Mountain Road between its northern junction with Devon Road and Inglewood.40

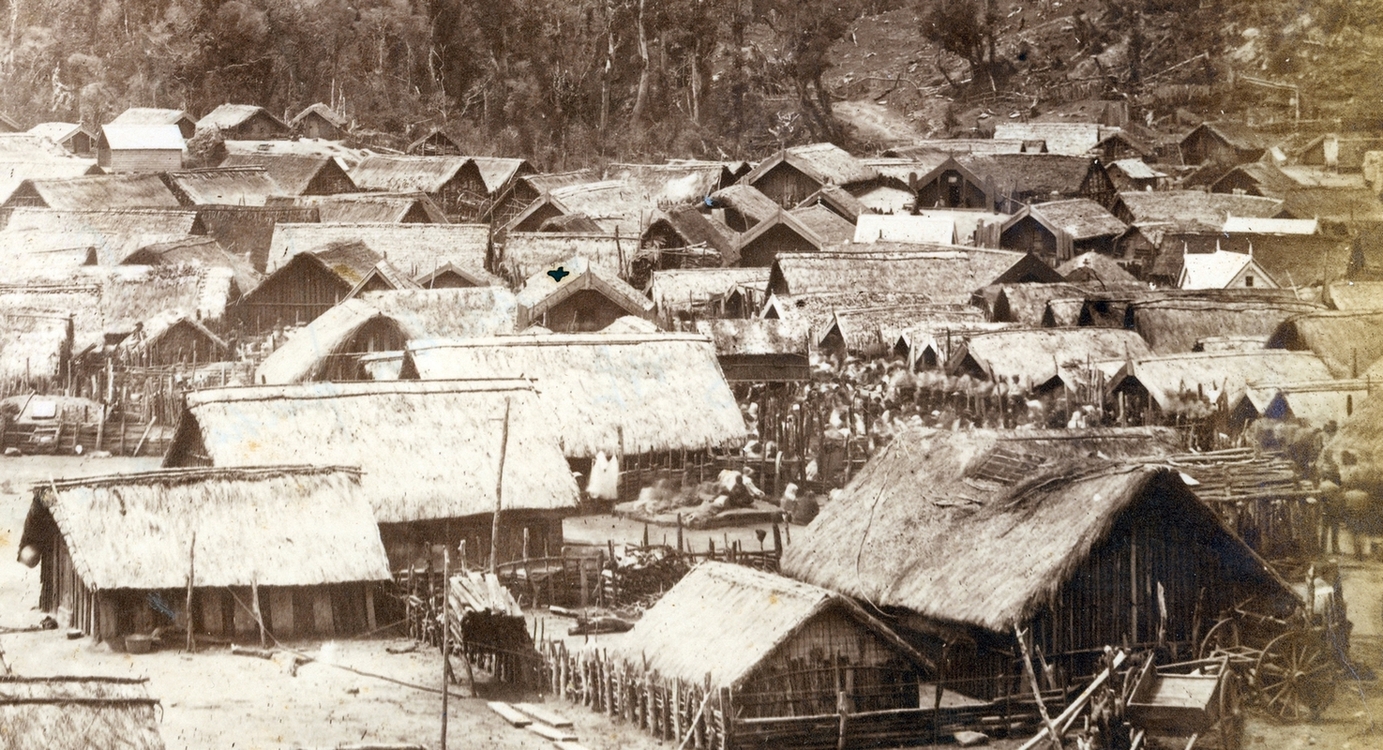

This photograph, with the same handwriting as the earlier photograph of the Inglewood settlement, seems to have been taken to the right of the vantage on Trimble Hill. If so, the two rows of huts on the right may well be the beginnings of Elliot street, which runs parallel to what became James Street behind and to the left. Again, there is no sign of the railway that would have marked Mountain Road, but the ditch and tree roots in front of the front house, the tree stump still in the ‘road’ and elsewhere, show how this township was wrested from a substantial piece of bush. (Photo: Puke Ariki –3)

It is not clear who first employed those early Poles. It is doubtful that any specific accommodation arrangements had been organised for them, but they would have been paying rent to someone. Family stories indicate that they built their first shelters near Jubilee Park, and took their water from the nearby stream that still runs along the east of the Inglewood cemetery. For years, the illiterate Poles were unaware that one of the roads along where many of them lived was named German Street.

Sister St Martha: “Grandfather and his family lived in that street for 10 years. The Poles found out about the name when someone who could read told them. They made such a fuss that they renamed it James Street.”

Back in October 1875, the budget correspondent noted that in Inglewood “affairs looked exceedingly brisk”41 and saw carpenters from New Plymouth working on large private residences, and buildings such as the town’s store and hotel. Without the ability to communicate in English when they arrived a year later, it is doubtful whether the Poles would have been employed in the town itself. Like Mathias Dodunski, most worked on clearing a desperately needed supply route to New Plymouth that did not rely on dry weather. Descendants of the early Polish settlers repeat stories of their relatives felling the bush, and building railway lines, roads, and bridges.

The caption to this photograph in te moa42 says: logging, brown’s hauler. It does not elaborate on what the wood was, or how long it took the eight men in this photograph to bring down the trees. The horses harnessed to the logs on the right, and the man, second from right, standing on what could be a wheel on a flatbed suggests that they hauled logs from various places towards the main logging railway line.

The early Poles could communicate in German—they had lived under Prussian partitioning—so may well have met and been guided by some of the German and Danish settlers off the humboldt who bought sections in Inglewood in February 1875. Seven or eight languages could be heard on the veranda of the first hotel, built at the southern end of Moa Street.43

By October 1876, “first class red pine [rimu] sleepers” were being delivered regularly to Inglewood from New Plymouth, and by that December, Colonel Trimble had announced that he was building Inglewood its own sawmill. Sawmiller Henry Brown junior also saw the potential in Ingelewood, and moved his New Plymouth mill to a section beside the railway line on Mountain Road.

The new passenger train on the Inglewood line made its first trip on 10 September 1877. Curious New Plymouth residents snapped up the half-price return fares and left the town’s streets deserted.

By January 1878, the bush had been cleared almost five kilometres north of Inglewood to the Waiongana bridge on Mountain Road, and by May 1879, the Junction Road leading west towards New Plymouth, “formerly one of the worst miles between Inglewood and New Plymouth [had been] very neatly metalled.”44

THE BIESIEK FAMILY

Paul and Marianna Biesiek married in 1864 in Garczyn, part of the Kociewian region of Prussian-partitioned Poland. Their Polish names were Paweł Bieszk and Marianna Krygel. For a time in Taranaki, Paul’s name was spelt the same as it had been on the fritz reuter passenger list—Bies—but the family soon became known as Biesiek.

Their daughter, Maria, died at sea, aged 20 months, but the Biesieks had at least three more children in New Zealand: Paul Adam, born in 1878; Joseph, born in 1881;45 and Thomas, born in 1888.

The 1882 return of the freeholders of new zealand46 shows that Paul Biesiek, settler, owned 60 acres in Inglewood, valued at £110. In 1897, he bought 143 acres at Huiroa.47

Early Polish farmers helped one another build their haystacks. The man on the far left of this one is unnamed, but the ones next to him are, from left: Jacob Kuklinski, Thomas Potroz, Francis Potroz, Joseph Biesiek, and Thomas Biesiek. It is not clear what year this photograph was taken, but it has appeared in several family stories.48

Paul Adam Biesiek married Mary Dravitzki in 1906. The 1908 Ratapiko school committee included Paul Biesiek, his brother-in-law Vincent Dravitzki, and John Stachurski.49

An item in the taranaki daily news in June 1918 illustrated the depth of New Zealand’s distrust of Polish heritage during times of war. It involved Thomas Biesiek’s appeal to the WWI Military Board for an exemption to be allowed to care for his then widowed 78-year-old father but referred to his brother Joseph’s military call-up in January 1917. The brief article was headed a question of parentage:

In the case of Thomas Biesick [sic] dairy farmer, Ratapiko, evidence was given that the appellant’s brother Joseph, after being trained, had been turned out of camp some 12 months ago, on account of his parentage, but as the outcome of his continued representation to Sir James Allen he had again been ordered into camp. Appellant would be willing to go into camp also, but that he had to look after his father…50

Sir James was then New Zealand’s acting prime minister and New Zealand’s war leader.51

In 1918, Joseph Biesiek married Mary Ann Potroz, born in Inglewood in 1895, and a niece of Anton Potroz. Joseph later worked for the Taranaki Electric Power Board, and made the newspapers again in 1932, when he was electrocuted by a live wire in a water-race at the Maungatea swamp at Ratapiko.52 Joseph and Mary Biesiek junior had no children, both lived to 85, and are buried together at the Inglewood cemetery.

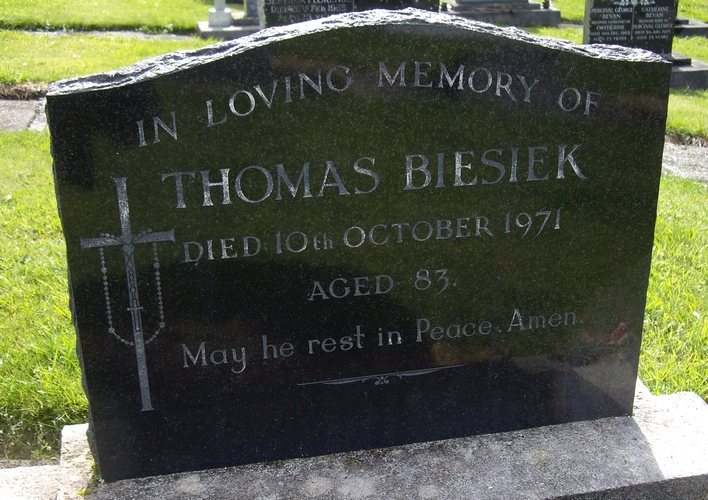

Mary Biesiek senior had died in 1916, aged 76. Paul Biesiek senior died in 1920, aged 80, and was buried with his wife at the Inglewood cemetery. Thomas, who died in 1971, is next to them.

The senior Paul and Mary Biesiek’s grave at the Inglewood cemetery.

Paul Adam Biesiek and Mary née Dravitzki’s headstone at the Inglewood cemetery.

Left, Thomas Biesiek’s headstone at the Ingleood cemetery stands next to his brother’s and near other relatives. Below, Joseph Biesiek and Mary Ann née Potroz Biesiek's headstone.

THE DODUNSKI FAMILY

Mathias and Apolonia (Paulina) Dodunski married in 1869 in Greblin, in the heart of the Kociewian region in northwest Poland.

Their mis-spelt name on the fritz reuter, Duschienski, probably came about because fellow passenger Barbara Duschenski (Polish spelling is Duszyński) was Apolonia’s younger sister. According to family story, a Dodunski infant died at sea but, as there is no mention of one on the passenger list, the fatality may have happened earlier. The Pomeranian birth index has a record of Augusta Paulina born to Mathias and Paulina Dodunski in Tczew in 1876, but no death record under her name, which suggests she may have died on the way to Hamburg, or soon after.53

Dodunski-Duszynski—in the hubbub of embarking on a full immigration ship, keeping an eye on a seven-year-old daughter, a two-year-old son, and the sadness of a baby’s recent death, no doubt pregnant Barbara hovered close to her sister. The name exchange was a mistake easily made.

Apolonia and Barbara were full older sisters to Franz Drozdowski, who arrived in New Zealand in 1883 with his own family, and their then 20-year-old sister, Julianna. They took the british king with Mathias Dodunski’s older brother Michael, and his family—the only other Poles on that ship.

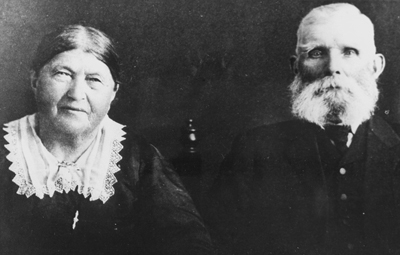

The Dodunski surname is prolific in Taranaki, and the family well-known for farming on Durham Road. When Mathias died in 1938, aged 93, a descendant listed his 67 grandchildren and 76 great-grandchildren.54

Apolonia and Mathias Dodunski, shortly before Apolonia died, aged 77, in 1928.

Mathias and Apolonia had nine more children in New Zealand: John in 1877; Thelka in 1880; Albert in 1881; Joseph Felix in 1882; Paul in 1884; Catherine (Kate), in 1886; Martha Mary in 1888; Anton Felix in 1890, and Mathias junior in 1893. Kate died aged three in 1889, and Paul was killed by a falling tree in 1904, aged 20, while working on the farm with his father. The taranaki herald in separate articles:

The funeral of Mr Paul Dodunski took place on Wednesday, and was one of the largest seen here for some considerable time, which shows the esteem in which the young man was held by his fellow settlers.55

Great sympathy is felt for the bereaved parents of Paul Dodunski, killed while bushfelling. They were very old settlers on the Durham Road.56

There were joyous celebrations too.

Dodunski brothers Albert and Joseph married a month apart, in July and August 1905. Both occasions packed the Inglewood Roman Catholic Church.

Albert’s bride, Frances Schrider, was born in New Zealand in 1884. Her Kociewian father, Martin, who brought his family to New Zealand in 1880, died in 1895, so her brother Robert gave her away. Around 200 people attended the wedding reception, held at the Dodunski farm on Durham Road. The Moa Farmers’ Union bakery made the cake and “provided the necessary sweetstuffs.” The newspaper described the “event of the evening,” the bride’s dance:

One lady takes her stand at one end of the room, with a plate held over her bunched up apron, the groom leads the bride out, and dances a few turns with her, then both his and her immediate relatives take their turns, after which the single men, and so till everyone in the room has danced a few steps. Each person is expected to deposit some money in the plate at the conclusion of their turn. I understand that the idea is a substitute to the practice (as with the Britisher) of giving presents, and when one learns that the sum collected totalled £37 15s 3d one cannot but admit that it has points over the present giving system. …valuable presents were also sent by those who could not be present and by those whose other duties prevented their staying for the evening’s amusement, which continued with unabated vigour up to 7am the next day.57

The unnamed reporter noted that every Polish family in the district was represented at the gathering, “and they are not a few.”

The large attendance, they said, testified to the popularity of the bride and bridegroom, and to the respect in which Mathias Dodunski was held:

…a pioneer of the Moa Block, and having in common with many others of the same nationality suffered the unavoidable hardships attendant to opening a new country, was still able to take his part with vigour in the activities, which were carried out in real Polish style.58

The wedding party of Frances Schrider and Albert Dodunski on 4 July 1905: From left, Paulina and Mathias Dodunski, bridesmaid Barbara Schrider sits in front of Joseph Dodunski, the bridegroom and bride, second bridesmaid Martha Dodunski seated in front of Reverend Father Long. The bride's widowed mother, Bertha, sits on the right, in front of her son Robert, who was born at sea.

Martha Dodunski was bridesmaid at both weddings. Joseph Dodunski married Joanna Wisniewski, daughter of Andrew and Barbara Wisniewski, who had also travelled with the Dodunskis on the fritz reuter. This time, the festivities were held at the bride’s home, around the corner in Rugby Road, which had a “large convenient barn (30 x 14) erected for dancing etc.”59

That reporter noted that, “Mr Wisnewski, who is another pioneer of the Moa Block, provided in liberal manner for the wants of the visitors.”

Durham Road had its own correspondent at the taranaki herald and the poor state of the road was a regular topic in the newspaper. Nearly 30 years after those first Poles walked into the Inglewood area and started working on its infrastructure, their own roads remained ignored. In June 1905, a month before Albert Dodunski’s wedding, the Moa Road Board had made £400 “available” for its metalling:

A considerable amount of time, and good time, too, has been frittered away, and no one seems to be answerable for such. It is a great injustice to the settlers on the mud road that this delay has been occasioned and it is evident that they will have to struggle through the slush for another season.60

Even when they left their neighbouring huts in Inglewood proper, the Poles tended to live near one another, often between Mountain Road and the mountain, which contained some of the last available sections. Unlike the main Inglewood area, their land was not pre-felled by others. The first eight Polish families, who were joined by those who left Jackson’s Bay and Hokitika, earned a wage elsewhere, and returned at weekends to clear their own pieces of bush. There is no doubt that the Poles living on a certain street contributed to the metaling of that street. Sometimes they worked for the good of their neighbours. Sometimes, in frustration, they pushed authority.

Mathias Dodunski was the eighth and youngest child of Mathias and Catherina née Lipienska. He was born in 1845 in Gręblin, which came under the parish of Wielki Garc. Apolonia Drozdowska was born five years later in Radostowo, a neighbouring village. They married in Subkowy in 1869, four months before Mathias’ widowed mother died. Family story is that Mathias wrote glowingly to his brother Michael about his new life, giving him inflated expectations.

Michael Dodunski arrived off the british king with his wife and six children in 1883, but was not impressed with what he considered the backward nature of the colony. Despite the problems for Catholic Poles at their birthplace, it had an established infrastructure. Perhaps the brothers’ only other living sibling, their older sister, Barbara, influenced Michael to stay. Barbara had arrived off the hudson in 1879 with her husband, Martin Potroz, and their family.

Bridesmaid Martha Dodunski’s daughter Sister St Martha Szymanski hated to run barefoot around the family’s Durham Road farm, and always wore gumboots to escape the mud. She found a path where she could jump from what she thought was one conveniently spaced log to the next, and discovered later that the ‘logs’ were part of the temporary tram line that used to take felled trees out from their property to Brown’s mill in Inglewood.

By 1 June 1878, Brown’s mill had a tramway over the Waiongana-iti into the standing bush that pulled out an average of 1,000 metres of timber daily. This photograph in te moa gives no year, place, or names, but the locomotive was clearly integral in moving the massive logs considerable distances. It is captioned in the bush.61

Apolonia Dodunska died in 1928, 10 years before her husband. They are buried together at the Inglewood cemetery.

In 1888, their eldest daughter, Franceszka Dodunska, who became known as Frances, married fellow fritz reuter passenger Joseph Mischewski (the six-year-old in 1876). They also lived on Durham Road and had 17 children. Those with years behind their names are recorded in the BDM under recognisable surnames: Pauline Juliana, born in 1889, died at seven months; Joseph William, born in 1890, died at 10 months; Ivy Catherine born in 1892; Felix; Agnes; Mary Jane born in 1897; Frederick John born in 1898; Albert James born in 1899; a second son named Joseph William, born in 1901; Andrew Frank born in 1902; Dorothy born in 1904; Paul born in 1905; Kathleen; John, known as Jack, born in 1906; James born in 1909; Helen Frances born in 1911; and Monica.62

Frances Barbara née Dodunska Mischewski died in 1956 aged 86, and is buried at the Inglewood cemetery with her husband, Joseph, who died in 1961 aged 91. (More on Joseph and the Myszewski/ Mischewski family later.)

Joseph and Frances née Dodunska Mischewski lie with their sons Paul and Jack at the Inglewood cemetery.

Franciszek Dodunski, like his older sister, was born in Radostowo. He became known as Francis and married Apolonia Lehrke in 1895. His bride arrived in Wellington as an infant with her family, off the terpsichore, four months before her future husband. Immigration officials sent Johann and Marianna Lehrke and their four children to Jackson’s Bay, on the South Island’s west coast. Their name had been germanised from Learka. They stayed at the controversial “Special Settlement” until December 1878 and were among the last Polish families to leave.63

Francis and Apolonia Dodunski had seven children: Andrew John in 1896; Monica Vera in 1900; Francis Mathias in 1902; Leo Valentine in 1904; Getrude Paulina in 1905; Rita Mary in 1911; and Constance Maggie in 1913. Francis Dodunski senior died 1959 aged 85, 11 years after his wife, who died aged 73. Both are buried at the Te Henui cemetery in New Plymouth.

THE DUSIENSKI FAMILY

After the prime pieces of land in Taranaki had been sold, the Waste Lands Board stepped in to dispose of the rest. The word “Waste” was not strictly descriptive, because it was land holding good trees. It was “waste” in the sense that it was left-over, —not what Kenworthy, the 1875 visitor to Inglewood, spoke of when he praised the area’s “good agricultural land.” Waste land tended to describe sections outlined along paper roads, on maps of uncleared land where the buyer had little idea what lay within.

By 1882, Joseph Dusienski had bought 59 acres in Inglewood valued at £88.64 By 1886, he was paying off the last instalment on section 195 Moa (Norfolk Road) and had set in motion his purchase of the neighbouring section.65 His naturalisation in 1887 as a farmer of Inglewood points to his being content with his new home and life.

He was another Kociewian Pole, born in Waćmierz in 1851, about five kilometres from his wife, who was born in Radostowo in 1854. Joseph Duszyński and Barbara née Drozdowska were married in Subkowy in 1874.

The couple’s first child, Maria Augusta, died 11 days after she was born in Inglewood on 14 November 1876. Her death certificate suggests that the living conditions near Jubilee Park were not ideal. It states that she died of “gradual decline” with no medical attendant. The “informant” was the Inglewood postmaster. There was no religious minister. Besides her father, the certificate states that witnesses to her burial at Inglewood cemetery were Maties Dodunski, Anton Potroz, and August Neustrowski.66

Joseph and Barbara Duschenski, as their surname became known, had six more children. Paulina, Agnes, Joseph, Teckla, Lucy, and Jack were aged between 11 years and 10 months when their father died in June 1890, aged 37.67

Paulina and Agnes Duschenski had brought their father his breakfast to where he was clearing bush about 800 metres from their house, and played nearby. They heard a tree fall, and his calls to them to fetch their mother, and saw that the tree he was felling had trapped him against another. Neighbours released him, and summoned a doctor from New Plymouth, but Joseph Dusienski died from his injuries days later.

The community rallied around the family. Someone applied on their behalf for aid through the Hospital and Charitable Aid Board, which that October confirmed an allowance for the family.68 Others organised a fundraiser that included entertainment by “all our favourite local amateurs.”69 On one Friday evening in November, the Midhirst hall was:

… crammed to suffocation. an imposing array of good things for the comfort of the inner man (and woman) had been provided by the ladies of the neighbourhood, and were done full justice. Dancing was kept up until daylight.70

Barbara married again, to Christian Christensen, and died on St Barbara’s Day in 1918. She had two more children with Christian: Maria and Martha, and is buried near her first husband at the Inglewood cemetery.

THE EXTENDED MYSZEWSKI FAMILY

The Myszewski family were one of the largest to disembark from the fritz reuter. Johann Myszewski had with him his new wife, Karolina, two nieces, and four children aged between six and 15. His nieces and 15-year-old daughter, Julianna, were the single women mentioned earlier, who were among the first of the Marsland Hill immigrants to be employed in August 1876.

An early transcriber listed the family in order as: Johann (41), Carolina (22), Johanna [sic, she was Julianna] (15), Jacob (13), Catharina (9), Franziska (1), Joseph (6), Lucia (3) and Johanna (2).71 They all had the same “passport” number—322—so any number of assumptions could have been made regarding the relationships within the group.

Lucia and Johanna were not toddlers of three and two, but young women of 24 and 19. They were not Johann Myszewski’s daughters, but they were probably his orphaned nieces. Lucia seemed to disappear, until she married an Alexander Leis in Sydney in 1884. She died as Lucy Leis, a week before her 89th birthday, and is buried at the Quirindi General cemetery in New South Wales.72

Johanna married Anton Szczodrowski (25) on 30 September 1876. She was the same age as his first wife, Julianna née Krakowska, who died in childbirth on Matiu/ Soames Island seven months earlier. Their names on their marriage certificate are spelt Johanna Meszenska and Anton Shawdrowski.73

The principal immigrant in the Myszewski family—Johann—married Marianna Dytmer in 1859, lived in Kokoszkowy, and had four children. Marianna died in February 1872, and Johann married Carolina Funk in Kokoszkowy in 1873. Marsland Hill immigration barrack’s lack of rations for their daughter Franciszka, born in September 1874, confirms that she did not survive the voyage.

Johann Myszewski became John Mischewski in New Zealand. Other branches of the family used the spelling Mischefski. He and Caroline had another eight children: Francis in 1877; Maria in 1878; Martha in 1880; John in 1885; Bernhardt in 1887; Anton in 1889; Thomas in 1892; and Agnes in 1893.

Caroline died aged 45, in 1899, and is buried at the Midhirst Old cemetery. Although the official birth records (BDM) of his children name him John, he was buried as Johann Mischewski, aged 86 in 1918. There are no Mischewski names still visible among the mostly broken headstones in the cemetery, but the memorial wall at the entrance shows Johann and Caroline, and three other Mischewski infants: Joseph William who died aged 10 months in 1891, George Thomas who died aged eight months in 1894, and George Nelson who died in 1901 aged two months.

The memorial entrance wall at the Midhirst Old cemetery on Beaconsfield Road in Stratford.

In 1877, Julianna Myszewski married Frank Uhlenberg, the single man in the group that walked to Inglewood the year before. BDM named them Juliana Myzzenski and Franz Ulenberk. (More about them later.)

Jacob Mischewski married Mary Jacobowski in 1885. The Jacobowski family of six was also aboard the fritz reuter. (Their variant of the Polish spelling is Jakóbowski.) Jacob Mischewski and his father were both naturalised as farmers of Midhirst on 25 October 1890. They appear together in the 1882 freeholders record as Johan and Jacob Myyenski. Then, Johann owned 40 acres valued at £206, and Jacob 42 acres valued at £180.74

Jacob and Mary Mischewski had 11 children: Katherine Anne in 1886; Leo Michael in 1887; Agnes in 1889; James Francis in 1892; George Thomas in 1894; Mary in 1895; Joseph Augustine in 1897; Barbara in 1899; Peter Paul in 1901; Anna Magdalen (Annie) in 1903; and Stephen John (Jack) in 1906. Jacob died in 1952, aged 90, and is buried at the Kopuatama cemetery in Stratford with his wife Mary, who died aged 80 in 1945.

Johann Mischewski’s daughter Catharina on the passenger list became known as Katherine, and married William Todd in 1900. She died in 1944, aged 77, and is buried with her husband at the Waikumete cemetery in Auckland.

In 1916, Joseph Mischewski (the one who married Frances Dodunski), Vincent Dravitzki, aged three on the fritz reuter, and Joseph Stachurski, aged two on the shakespeare in 1876, represented Inglewood’s Polish community in a protest to Members of Parliament Henry Okey and William Jennings about the enemy alien classification that they received earlier that year.

The Poles were told that they had to report weekly to the Inglewood police station, and that they had to carry a police permit if they travelled beyond 20 miles.75

The taranaki daily news, under the heading the poles of inglewood classed as “enemy aliens” and sub-heading a strong protest:

The deputation… represented that although not naturalised British subjects, being Poles by birth, they had no sympathy whatever with the Germans in the present war. Indeed, their fathers left Poland because of the tyranny of the Germans. Most of them arrived in Taranaki almost forty years ago, and had been loyal subjects ever since. They pointed out that they were under the impression until the war broke out that they were naturalised British subjects on account of their being here for over twenty-five years.76

Then, Joseph (Joe) Mischewski had 14 children and had been living on Durham Road for 20 years, 14 of which had been spent as a school committee member. Vincent Dravitzki had 10 children and had been a farmer in Ratapiko for “many years.” Joseph Stachurski was a director of the Moa Dairy Company, a member of the school committee, and was active in the district’s public affairs. He told the MPs that:

… the Poles knew only too well the methods of the Germans. They had cruelly treated their fathers in Poland for many, many years. It was only now that outsiders could appreciate the dreadful cruelty that inspired the German’s actions in regard to subject people. For a Pole under British rule to wish them well or sympathise with them in any degree was unthinkable. The Poles of the Inglewood district felt humiliated at being classed “alien enemy subjects.”77

MP Jennings said he knew the Poles for their “loyalty and industry” and work in the district. Although the MPs said they would “strongly recommend” to the Minister for Internal Affairs that he “remove the restriction upon the liberty of the Polish settlers,” Polish names remained on the 1917 Enemy Alien register.

The sensitive topic of aliens raised itself again in 1919, after Robert Masters won the Stratford general election by 61 votes from incumbent Captain John Bird Hine, who petitioned against the result. Although Hine’s petition revolved around Masters allegedly bribing voters with free “music and pictures,”78 several Poles became embroiled in the March 1920 petition proceedings because they had had the temerity to vote.

If the Taranaki Poles thought that their 1916 protest about being considered enemy aliens had amended their status, they soon discovered that nothing had changed and that they still had no right to vote. Instead of being able to send delegates to speak to MPs on behalf of them all, individual Poles had to defend their characters in a public court.

Joseph and Franceska Mischefski’s names joined those of Barbara and John Burkett, Rose and Vincent Dravitzki, Joseph Stackurski, Barbara and Frank Bilski, Joseph and Mary Dodunski, Polly and Vincent Kowalwski, Frederick and Martha Mary Voltzke, Mary Groshieneski, Augusta Dombriski, and Annie Habowski. (These spellings from the newspaper article.)79

Justice Chapman heard Paul Biesick[sic], Jacob and Mary Kuklinski, Frances and Anthony Wisniewski, Michael Bieloski [sic], Augusta Dombroski, and Valentine Bilski, and concluded that their “impression [of being eligible to vote] seemed general.” In his lengthy judgement that declared the election void, however, Justice Chapman did not mention the Poles, or the eligibility of voters.

After he lost, Hine and two others took a petition to the Election Court, which included a specific allegation about…

… a large number of people who were registered as electors and voted in favor [ sic] of the said Robert Masters… were not entitled to be registered as electors, or to vote and had been disqualified by legal incapacity and whose names were illegally placed or retained on the roll and your petitioners say that all such votes ought now to be struck off the poll.80

Votes for Hine versus Masters showed that in 1919, the politicians’ popularity varied in some of the places where Poles lived: Inglewood, 394 vs 315; Durham Road, 34 vs 28; Midhirst, 73 vs 128; Norfolk Road, 68 vs 67; Ratapiko, 19 vs 30, which brought the totals for those areas to 588 for Hine and 568 for Masters. The 1919 Stratford election had been tight, but Hine’s including easy targets like the Poles for his loss seemed unfounded.81

The by-election held in May 1920 increased Masters’ majority to 148. In 1922, he retained his seat by a majority of 363 over Hine.

THE NEUSTROWSKI FAMILY

August and Apolonia née Potroc Neustrowski were another example of the close familial relationships between the Poles who first landed in Taranaki.

Apolonia was a full sister to Anton Potroc, whose wife, Josephine, was a sister to Johann Myszewski’s second wife, Carolina. When 18-month-old Franciszka Myszewska died of the same heat exhaustion as seven-month-old August Neustrowski, their family ties may have eased their shared grief.

Marianna Neustrowski, aged five in 1876, told her grandson Ray Watembach that heat exhaustion affected many of the youngest children on the fritz reuter.

Born in the Mątowy Wielkie parish, August Nejstrowski was orphaned as a young child and taken across the Vistula to Wielki Garc where the Potroc family cared for him. Ray has traced the original family name, Nesterowski, to 1773 parish marriage records in Klonówka. August married under the name Nejstrowski in 1870, the same name recorded for Marianna and her brother Johan. The surname of his second son, August, born in 1875, was recorded as Neistrowski. All the children were born in Kociewian Gręblin.

After their daughter Agnes was born in Bell Block, the Neustrowskis moved to the new Inglewood settlement, and first lived with Anton and Josephina Potroz near the other Poles in the Jubilee Park area.

Ray: “My grandmother described it as ‘one room, with a lean-to at the back for washing and drying clothes.’ The room had a dirt floor and they made dried fern mattresses. The parents slept on the floor and the children in the rafters. The fireplace was about two metres wide and about a metre deep. It didn’t have a brick chimney, so they lined it with corrugated iron supported by green timber. Once they had a bit of money, they bought pork and started making Polish sausage, curing hams, bacon, or even fish, by hanging it all in the chimney.”

Marianna (who became known as Martha Watemburg after she married) and her brother Johann (who became John, or Jack Neustrowski) attended classes at a private school in Inglewood until the first official school was opened, but left aged 10 to help care for her younger siblings: After Agnes, came Paul in 1880, Joseph (Joe) in 1882, Bernard (Ben) in 1884, Apolonia in 1886, and Isidor (Sid) in 1888.

Between 1877 and 1880, the Waste Lands Board offered 50- to 100-acre sections between Tariki and Midhirst, sight unseen, at £1 to 30 shillings an acre, and by then, August had managed to gather a deposit. The 1882 freeholders register showed that he owned 85 acres in Midhirst, valued at £131.82

The section was packed with tangled vines, ferns, and trees as tall as 30 to 40 metres. If General Chute’s 500 soldiers did not pass directly through it, they would have been close by. On paper, it was on York Road, but there was no road then, and many unbridged streams between it and Inglewood proper, so the family remained in Inglewood for several years after the sale.

Having their own piece of land again was important to the Poles, who had lost their farms and livelihoods under more than 80 years of Prussian partitioning of Poland. Ironically, they had immigrated to a country where the new occupiers had done exactly the same thing to the Māori as the Prussian occupiers did to the Poles in 1775, 1792 and 1795.

In 1881, August had a job at Browns Mill in Inglewood. Without an army to help, it took him until the early summer of 1886 to clear enough of his land to grow grass for a few cows, and build a dwelling for the family. Agnes remained at the Inglewood school, and John transferred to the Waipuku district school near Mountain Road.

The Neustrowski’s York Road farmhouse circa 1904. On the veranda from left are brothers Ben, Joe, and Paul Neustrowski. Agnes, then married to Herman Schultz, is seated with her children, Joe, Margaret, and Helen. Apolonia (Polly) is standing on the far right. Standing in front of the veranda on the far left is August Volzke junior, a family friend, and son of August and Emilie Marie Volzke. (More on the Volzke family later.)

August created a safe over a drain of running water to keep milk and butter cool. In winter, the family cows foraged in the bush. Martha sold the butter in Stratford, walking the 11 kilometres and returning with provisions. On Sundays, the entire family walked to Mass in Inglewood. The building of the Catholic church in Stratford cut that journey considerably.

As with all the Polish settler families, children helped where they could, and the Neustrowski children scoured fallen logs for fungus to dry and sell to local businessman Chew Chong, who had found a ready market for the product in China. He paid them three pence a pound.83

Ray: “He was well-known, and saved many a Polish family from starvation. He had a house in Eltham, and then moved to New Plymouth, where it was better for him to run his export business. People knew he’d be on the train on certain days.

“Every road that crossed the railway line had a little station. The children waited for the train to come through the station, and not just the children, the adults too. The train did deliveries and stopped at each road. The farmers got things dropped off, from bags of cement to a dress ordered.”

The tradition of stopping where needed continued until at least 1947. Ray remembers his grandmother, who had by then moved to Waitara, deciding to visit her son Leo on his Norfolk Road farm. She took Ray and his older sister, Shirley, with her, and the train duly stopped at the bottom of Norfolk Road. Ray had hoped his uncle would meet them to help them carry their bundles up the road, “but he was busy on the farm.”84

August Neustrowski continued to add to his York Road farm. A Land Board notice in the hawera & normanby star on 17 February 1897 declared that “A Neustrowski” had acquired the freehold on section 228, Moa, a neighbouring property to the one he had bought next to his brother-in-law Anton Potroz in 1890.85

August’s sons Joe and Ben—like other Polish sons— became so adept at bushfelling, that in the early 1900s, they provided fierce competition at sports meetings and shows such as Eltham’s annual Axemen’s Carnival.

Entries in January 1908 for the Inglewood Caledonian sports day 18-inch Open Handicap included the Polish teams of Bielawski and Roguski [sic], the Dravitzki Bros, JP Bilsk [sic] and Dravitzki, and the Newstroski [sic] Bros, names repeated elsewhere in the programme.86

In 1905, Ben Neustrowski won the most prominent of the three New Zealand contests—the 18-inch Underhand World Championship—but only after August Voltzke senior, another of the first Poles off the fritz reuter, proved the result with a photograph. Split-second decisions regularly went against the Poles. At a show in 1912, judges conceded that:

… there is a possibility that a mistake could have been made: and whilst the club cannot honour the win to Neistrowski, who disputed the decision, the members have generously subscribed the amount of the prize money, and handed it over to him.87

August Neustrowski became naturalised in Inglewood in 1887. His sons Joe and Paul joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in 1914, and both served in western Europe for more than two years, and his son Sid was called up in 1917—yet after 40 years in New Zealand, the New Zealand government still considered their 67-year-old parents enemy aliens. The soldiers’ siblings Martha and John received the same treatment.

This 1914 Neustrowski family photograph was taken as a memento before brothers Joseph (Joe) and Paul joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Seated from left is Martha, Isadore (Sid), Apolonia senior, August, Apolonia junior (Polly), who married Ben Dombrowski, and Agnes, who married Herman Schultz. Ben is standing behind Martha and John is standing on the far right.

Martha married Joseph Watemburg in 1897, and moved to Marshland in Christchurch, where several of the Poles who arrived off the friedeburg in Lyttelton in 1872 were making a name for themselves as market gardeners. Martha returned to Taranaki with her sons after Joseph died from a heart attack in 1915, and lived in Waitara until her death in 1960.

John, who had taken over the York Road farm, was widowed in March 1922, when his wife, Rosalie née Meller, gave birth to their 12th child. It is not clear how many of their children were still living at the farm—their eldest, Kathleen Polly had married August Dodunski in 1920—but the youngest six were aged from 16 months to 10 years. Milk fever among his cows destroyed John’s farming career two years later, and he moved next door to the Potroz farm while his parents took over his mortgage and returned to the property. John found work at the Waipuku Quarry, retired to Opunake, and died aged 85.

Sid Neustrowski died in September 1926, aged 38. August and Apolonia died within seven months of each other, August in February 1927, and Apolonia in the September. They are buried together at the Midhirst Old cemetery, near Sid.

THE POTROZ FAMILY

Anton Potroz and August Neustrowski paid 9d an acre in 1890 for adjoining leased sections on York Road.

Anton was the older son of Martin and Barbara (née Dodunska) Potroz, who followed Anton and his sister Apolonia to New Zealand in 1879. They sailed on the hudson with their three youngest children, Mary Martha (18), Thomas (16), and Barbara (9) Potroz.

Born in Gręblin as Anton Potroc, he lived in Rudno, about three kilometres south. In 1873, he and Josefina Funk were married at the Catholic church in nearby Wielki Garc. They boarded the fritz reuter with their son, Jacob Franz, born in 1874. Their first daughter, Julianna, lived for either eight or 12 days in January 1876.88

They had another 10 children in Taranaki: Jane in 1877; Mary Agnes in 1878; Franciska in 1880; Anthony in 1881; John in 1882; Augustus in 1885; Barbara in 1887; Leo Joseph in 1888; Louis Thomas in 1890; and Martin Dominik in 1892. Apart from Augustus, who died in WW1, the children all married into the wider Taranaki Polish community—families such as Christensen, Crofskey, Dodunski, Dombroski, Fabish, Schrider, Stachursksi, and Trebes.89

Jacob Frank Potroz married Mary Schrider in 1899. They also settled on York Road, and brought up their own large family. In the spirit of Polish hospitality, the Potrozes offered their paddock for the York Road school picnic in April 1918. The weather was “beautiful” and the function “proved to be the greatest affair of its kind ever held on the road.” Games, food, and residents’ donations of silver coins for prizes kept the children happy, and WWI at bay.90

The war brought worry, sadness, and relief. Josefina Potroz died in 1903, aged 53, so was spared from mourning the loss of her son Augustus, who died on 17 September 1916, aged 31, of wounds sustained in battle. A private from the 2nd Battalion, Wellington Regiment, NZED, he lies with other World War casualties at the Étaples Military cemetery at Pas de Calais in France.91

For the 75th and 100th anniversaries of the start of WWI, Ray Watembach travelled to the Catholic churches in Wielki Garc and Kokoszkowy, which held Potroz, Dodunski and Neustrowski records, and arranged to have Masses said there for New Zealand Polish descendants who were killed in both World Wars.

Josefina was also spared the demeaning irony of being branded an “enemy alien” of New Zealand while her sons went to war with the NZEF. Martin served in WWI for nearly three years and Louis Thomas for more than two, like Augustus, in western Europe.

Exactly like his sister and brother-in-law, and so many other early Polish settlers, after 40 years in New Zealand, the government put 64-year-old Anton Potroz, then living in Waitara, on the enemy alien register. And yet in France, the war cemetery describes Augustus as “Son of Anton and Josephine Potroz, of Poland.”

WWI soldiers unwittingly returned to New Zealand with the influenza virus, which killed about 9,000 people in New Zealand between October and December 1918. Illness and deaths dominated the personal columns of newspapers, and on 21 November 1918, the taranaki daily news listed Augustus’s older brother John among those who had died of pneumonia the previous day.92

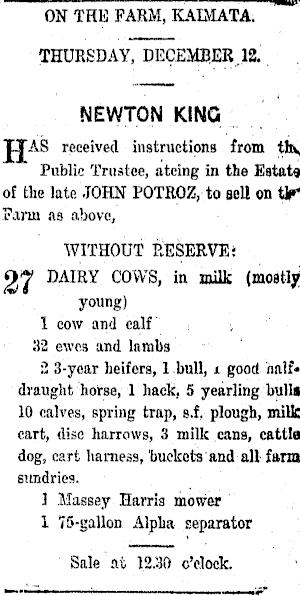

John Potroz had married his sister-in-law, Julia Schrider in 1908 and was farming nearly 200 acres in Kaimata. Their first child, Rose, drowned when she was two in February 1912. Four months later, Lewis John was born, followed by Lawrence William in 1913, and John James in 1915. Without John, it was inevitable that the farm had to go.

Barely three weeks after his death, the first of John Potroz’s stock and plant went up for sale.93 Another auction was held at the Inglewood Yards in January 1919,94 and the land was auctioned the following May.95

Mourners again packed the Inglewood Catholic Church for Anton Potroz’s funeral in July 1926. He had died, aged 74, at the home of his daughter Mary Agnes Stachurski. He was remembered in the stratford evening post for buying his farm on the York Road more than 50 years prior, when “the road was only survey and all in standing bush,” and for the “considerable amount of contracting” that he did before the road was formed, which allowed him to take up dairying.96

THE UHLENBERG FAMILY

Frank Uhlenberg had a job to do when he landed in New Plymouth in 1876: pave the way for his parents, Jan (John) and Rosalia, and younger siblings Joseph, then 23; Julia, then 20; Anna, then 17; Maria, then 16; Matilde, then 13; and August, nine in 1876. Frank was one of the few literate Poles on the fritz reuter. His father married under the Latin-Polish spelling of his name, Johannes Ulenberg, which also appeared on his children’s christening records.97

Frank was young, single, and exactly the kind of immigrant that the New Zealand colony needed, and recruited, under the Vogel scheme—for what former Taranaki provincial councillor James Crowe Richmond called “bone and sinew” that could work the land; different from the earlier Wakefield notion of transferring “full blown” British society into the new colony.98

Once Frank had established himself, he was to send for the rest of his family. Like his brother Joseph, he was born in Grabowo Kościerskie, west of Tczew, in northwest Prussian-partitioned Poland. Judging by the birthplaces of the youngest three siblings—Sikorzyno, Trzepowo, and Lubieszyn—the Uhlenbergs had joined the hundreds of Poles who moved from village to village to find work.

Frank and fellow fritz reuter passenger, Julianna Mischewski (Johan Myszewski’s eldest daughter, the one mis-named Johanna on the passenger list) married at the Catholic church in New Plymouth in August 1877. It is not clear what happened to Julianna when she was first employed out of the Marsland barracks, but she must have kept in contact with her father and siblings in Inglewood.

Little more than two years later, Frank had saved enough to sponsor his parents and siblings as nominated immigrants to New Zealand. They arrived off the orari in July 1879, his parents hiding the fact that they were then aged 60 and 61. The colony only accepted able-bodied labourers, so they fudged their ages to 46 and 44. From Wellington, they took a coastal steamer to New Plymouth, then still without a wharf, and reached the shore in the same two stages as the surveyor Browne described: A dinghy met the steamer, helped the passengers jump on, and rowed them to shore.

Frank’s great-niece Joan Dickson: “Frank and Julianna had prepared for the new arrivals. They had built a new ponga house for themselves a little distant from their original home. The old home was vacated, its ponga walls hung with fresh drapes, the mud floor swept clean, fresh bracken gathered for their beds, slabs of tree trunk cut lengthways to be used for table and seats, and a window fitted. The day before their arrival, Franz travelled on horseback to New Plymouth and bought a pane of glass, which he put into the house, the first on the York Road to have a window.”99

One has to accept that Frank knew when his family was arriving, and that he met them. There is no way that the Uhlenbergs would have been able to get from the New Plymouth waterfront to his farm in the bush without a guide. Frank would have been familiar with the town, and would have wanted to escort his parents and siblings, and possibly show off, just a bit.

After a night at Marsland Hill, they caught a train carrying ballast towards the railway still being constructed south of Inglewood. They sat on planks laid across the trucks as the train made its way through the walls of trees. They stopped at what was then the end of the track, known as the Manganui railway station, and made their way along York Road, through the supplejacks, bushes, trees, and logs, to Frank’s ‘farm.’100

Julianna Uhlenberg met them and introduced them to their first grandchild and niece, Barbara Franciska, born in June 1878.

Family story has it that, like so many other Poles writing ‘home,’ Frank worded his letters carefully. He glossed over the hardships, so no matter how meticulously he and Julianna prepared the new home, it must have been a shock for the continental Europeans to suddenly face living in such dense forest in such primitive conditions. According to the family story, Julia and Anna left the next day, and found work at the White Hart Hotel in New Plymouth. It is not clear when Maria left for Auckland.

It may seem odd that young women—new immigrants and not speaking English—would be prepared to immediately return to a town they did not know, but Julia and Anna fitted exactly the demographic that employers wanted in those days. One can imagine that they were offered jobs almost as soon as they stepped ashore, or had found out about jobs at the immigration barracks. As long as someone helped them through the bush to the railway line, they were assured of a trip back to New Plymouth.

After Frank taught his brother Joseph the art of bushfelling, he was soon employed and moved on, but Mathilde and August remained with their parents for a time.101

The senior Uhlenbergs must have made peace with their new home, because they bought a small farm opposite Frank’s and settled in to become doting grandparents.102

Julianna née Myszewski Uhlenberg with seven of her eight youngest children. Standing at the back, from left are Clara, Anna and Rosalia. In front, seated, are Martha, and Julia on the left of their mother, and Mary and Joseph to the right. The caption in the Uhlenberg family story says it was taken around 1900.

Frank was a conscientious farmer, regularly auctioning his dairy stock, and hand-milking one of the largest herds in the district.103 According to the BDM, he and Julianna had 10 more children: Johan Franz in 1879; Francis junior in 1881; Osmund Augustus in 1883; Clara Agnes in 1885; Anne in 1886; Mary Frances in 1888; twins Rosalie and Joseph in 1889; Martha in 1891; and Julia Helena in 1895.

Francis Uhlenberg junior died in a horse-riding accident 1901, aged 19, and his mother died in 1908, aged 48. Frank senior appeared to give up dairying four years later, when the following advertisement appeared in the hawera & normanby star:104

The Newton King advertisement in 1912, declaring Frank Uhlenberg’s intention to retire from dairying.

Frank senior withdrew his farm from sale, and was still working on the morning of his death in December 1915, when he and his son John took their milk to the Midhirst factory.

His inquest showed that he often visited his daughters, and Julia in Midhirst assumed he was with her sister in Waitara until she visited at Christmas, and found him missing.